By Janet McGovern

Last year’s series of devastating natural disasters seemed almost Biblical in their fury: Hurricanes and floods first in Texas and then in the Gulf. Closer to home, wildfires swept through the North Bay last October, only to be echoed in the Los Angeles area holocaust before Christmas. Even closer yet, the Skeggs fire in September burned for four days along the Skyline and in the Woodside hills before it was stopped.

Bay Area residents, who get regular warnings about the coming Big One, were jolted awake Jan. 4 by a 4.4 magnitude earthquake centered on the Hayward fault line. More recently, news outlets carried a Colorado State University professor’s assessment that California has been in an “earthquake drought” for years, with the San Andreas Fault system particularly stressed to unleash a temblor to rival San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake.

Forewarned, theoretically, is forearmed. Emergency kits should be ready to grab, 72-hour water supplies stockpiled at home, and, a pair of shoes stowed under the bed to jump into if the windows shatter in a 2 a.m. earthquake. Yet, with apologies to Henry David Thoreau, the mass of men actually lead lives of quiet procrastination.

“It’s human nature,” says the San Mateo County Office of Emergency Services’ Jeff Norris. “If something happens, there’s a brief flurry of enhanced preparedness. People get a little more ready, and then because it doesn’t happen all the time, they become complacent . . . It’s that project that you start that you never get finished. And preparedness for yourself and your family, especially in California – California is an act of God theme park, and you never know when we’re going to get that rollercoaster ride of the earthquake.

“But because it doesn’t happen on a regular basis, or it didn’t happen to me, or it didn’t happen to you, it’s easy to say, ‘Oh well, I’m prepared enough.’”

For someone not constantly aware of and planning for emergencies and disasters because of their job, figuring out how to get ready is easy to put off, especially contemplating catastrophes that, while assuredly real, may seem remote possibilities.

“Unfortunately, earthquakes are always there,” Redwood City/San Carlos Fire Chief Stan Maupin observes, “but they’re kind of at a low level. But they’re always there. The kind of fire that blew through Santa Rosa was so out of the norm that I think the public kind of says ‘Oh my gosh, oh my gosh. Oh, that can’t happen here.’ And then they’re back to day-to-day (living).

“What happened in Santa Rosa would be like a fire coming through Mount Carmel, through neighborhoods. It’s almost impossible for the public to even comprehend. How does a firestorm like that in the 21st century move through a neighborhood?”

From his vantage point of 30 years in the fire service, Maupin “was able to process it because you knew that there’s a time when the planets align and all those factors come together with the winds that they had up there, the dry vegetation, with the low humidity. I was surprised but not shocked.”

San Mateo County possesses a robust emergency response system that relies on automatic aid kicking in for “borderless” assistance when it’s needed. If a fire breaks out in one city, for example, firefighters from the nearest station roll out, beyond the city limits. (The Redwood City Fire Department since 2013 has also provided service for the city of San Carlos under a contract. The two cities have seven fire stations.) The same principle applies to mutual aid at the next governmental levels up. Municipal public safety services and fire districts are members of a countywide operational organization, which in turn is part of six statewide regions.

When major incidents happen, such as the Skeggs fire or the San Bruno pipeline explosion in 2010, Norris and his coworkers at the Office of Emergency Services are taking in information, developing plans, and predicting future needs. The same process is at work with larger-scale disasters such as the North Bay fires, where teams from all over the state – and beyond – were requested.

Every city in San Mateo County supplied people for the wide array of assistance that was needed, including an average of 50 police officers a day plus three fire strike teams. Each strike team includes, five engines, a battalion chief, and four firefighters per engine, but additional crewed engines went too, Maupin says. Public agencies that could spare them sent staff with specializations such as logistics, planning and public information. Their time away ranged from two or three days to a month.

Firefighters bid to be a part of these seasoned strike teams and are well aware that they may be deployed for long-distance duty. Usually the calls come with several hours’ notice, says Maupin, enough time to pack clothes and other personal items the firefighters will need. “But with Santa Rosa, they said we need them now.” The chief is quick to add that when equipment is sent out of town, other firefighters are called to come to work so the stations don’t stay closed for long. “We always staff up,” he adds. “We close these stations maybe a couple of hours at a time to staff these events and we get reimbursed (usually by the state) dollar for dollar for all the time our crews are at fires.”

By the luck of the draw, some of the firefighters who were sent to Santa Rosa and Los Angeles were newer employees, “and they came back wide-eyed,” Maupin says. They were able not only to gain a type of firefighting experience they rarely get but apply lessons learned to their jobs in Redwood City and San Carlos.

Chris Rasmussen, a Redwood City police officer who handles the department’s social media outreach, was staying with his family in Forestville, 18 miles from the Santa Rosa fires, but was affected nonetheless. Power was out and cellphone reception was spotty, but thanks to an old AM-FM radio that they scrounged up, the Ramussens were able to hear about evacuation orders. People in some areas were told not to drive, while others were told to get out, and it was hard to know what to do.

“You could see smoke and we had no information as to where it was,” he says, adding that the family packed up the truck and got ready to go. “I didn’t want to get the family out and get stuck in a big traffic jam.”

His takeaways from the experience: Messages need to be crafted both for those directly and indirectly affected, but the social media tools he relies on every day to communicate with the public may not be available. “Our communication method may be broadcast radio,” he says, and encourages people to keep a portable radio on hand. “As a department, we need to make connections with local radio stations. That’s something in the police department that I plan to do.”

Of the big fires, Maupin says, “I think we’re to the point in the state of California where we’re going out relatively so often that they’re becoming not that unusual anymore. We’ve joked about it for many years but the reality is the fire season is year-round now.”

That’s all the more reason for the public agencies’ emphasis on prevention, planning and preparation, as well as public information so residents can better take care of themselves and even their neighbors in a crisis.

Much of the work isn’t broadly visible. Fire department teams contact residents in more heavily wooded areas such as Emerald Hills about the need to trim back overgrowth, and the department has become more aggressive about trying to get open space and other publicly owned areas such as Stulsaft Park or San Francisco Water Department easements cleared back.

Redwood City does emergency drills for city staff at least once a year, according to Battalion Chief Dave Pucci, and long before the North Bay fires was planning the update of the city’s emergency operations plan that has just begun. The county, for its part, is providing new super-hardened quarters for the critical emergency functions in a building scheduled for completion in 2019, in the government center complex. Dispatch services for the sheriff, countywide fire departments and ambulances, as well as OES, will be in the building, according to Norris. It will have two of things that had better not go out in a disaster: two generators for two sets of power, two sewer and water lines and two phone lines and two sets of fiber optic cables.

During the Skeggs fire last September, OES personnel worked on contingency plans if the conditions changed and the fire suddenly spread, says Norris, who is the emergency services coordinator. Had the worst happened and people needed to be evacuated out of harm’s way, notifications would have gone out several ways. The county’s three community colleges (including Cañada) and Half Moon Bay High School are outfitted as evacuation centers and can be set up in a matter of hours to shelter up to 500 people.

“They have certain features about them that make them ideal for evacuation centers and shelters,” Norris explains. “They have big parking lots. They have big gymnasiums with a big open space. Gymnasiums have lockers and showers and restrooms and the colleges have kitchens.” They also have their own generators.

The easiest thing people can do to prepare for a disaster, Norris says, is to register with the free alert notification system used to immediately contact the public about urgent or emergency situations. Alerts can be set to send emergency and non-emergency text and voice messages to email accounts, cell or smart phones and tablets, or voice messages to landline phones. To sign up, go to www.smcalert.info. The site also has other information to help residents get ready.

Daniel Paley of Redwood City got his first taste of emergency training at work about nine years ago and had an appetite for more. He took a course through the fire department called the Community Emergency Response Team and has gone on to help train new enrollees with tasks such as trying out two-way radios or putting together pieces of wood (called box cribbing) to use, with a fulcrum, to free victims trapped under rubble.

“It’s a little bit of knowledge and the ability to act,” says Paley. “We learn some mechanics, how to crib and block, do a simple search and rescue, use a fire extinguisher.” In a major disaster that stresses infrastructure to the point that residents are left to themselves, “we can sit here and be victims or we can help ourselves.”

A systems engineer who is also a ham radio operator, Paley has an earthquake kit at home and has taught his whole family how to turn off the water and the gas if they have to. “It’s kind of always in the back of your mind that you should be prepared,” he says. “But no one does. People will want to help out but if your knowledge is limited, you can’t help much.”

Robert Lameijn moved into Redwood City a little over a year ago from the Netherlands, where he’d had some medical training in the Army that he found fulfilling. He’d always been impressed by how willingly Americans go anywhere in the world to help people, and he wanted to do his part in his home-away-from-Holland. “I’m a very proud non-American,” he says, laughing.

But it was the Jan. 4 earthquake in Berkeley that prompted him to sign up for the six sessions of CERT training that month. “I definitely want to be involved in the community,” he says.

The course is taught once or twice a year by the fire department’s community outreach coordinator, Christy Adonis, and several CERT volunteers. The curriculum is under the auspices of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and those who complete the program and get certified potentially could be called upon in an emergency to assist city forces. Participants in the initial, basic course get instruction in such potentially lifesaving techniques as how to stop bleeding or care for wounds, how to create a splint from cardboard or whatever is at hand, or how to open the airway of someone who has stopped breathing.

Participants come away with some easy tips, such as storing a pair of shoes and a flashlight under the bed, or getting a paper map of the city, since the Internet may be down in a disaster. “Broken glass and cut feet are the number one injury after an earthquake,” Adonis tells her students.

Though participants gain useful knowledge for themselves and others, Adonis emphasizes that they must assess conditions carefully in a real event so as not to become a victim themselves trying to help. CERT graduates also have to wait to be called and cannot “self-activate.”

To get a certificate, participants must attend all sessions, which includes a final skills day at the downtown firehouse, where Paley and other volunteers who participate in ongoing CERT training and activities give them hands-on lessons. The CERT trainees get to see how to turn off the gas. They attack a small, albeit controlled, blaze with a fire extinguisher. They conduct a building search in the darkness, finding “victims,” noting their condition, and then posting the information on the door of the building so anyone who comes later knows it has been searched and what was found.

“You have to work as a team,” volunteer Jane Ammenti tells them. “You’re constantly aware of your team. A lot of this is common sense, and if you need to do it, you will be able to do it.”

She signed up for CERT training in 2009 after moving to Redwood Shores and considers herself very well prepared to help herself and her neighbors in the bayside community. From first aid kits and gloves to pickaxes and hardhats, she and her husband, John, won’t be caught flatfooted.

“I know if the Big One happens, we’ll be cut off from everyone,” she says. “No matter where I am, I have (an emergency) bag in my car.” If one or both of the freeway overpasses into the Shores goes out of service, she points out, clearing the freeway may take time. First responders may not be able to get there right away, but she and her husband have first-aid training so they can help others.

“God forbid if there should be a natural disaster,” she vows, “I’ll be prepared.

Redwood Shores has had a fire station since 1998, and Sandpiper Community Center could be opened as an evacuation center if needed. Chief Maupin says the department plans and drills for a variety of scenarios, but notes that if the Shores were completely cut off, “the magnitude of the disaster would be unprecedented.” The Holly Street interchange will be rebuilt to the latest seismic standards as part of a major freeway project that is tentatively scheduled to start in September, according to San Carlos City Engineer Grace Le. Completion would be in 2020.

Not everyone has 20 hours – or the interest – to take the full CERT training. The fire department also offers a free one-to-two-hour disaster preparation class called “Are You Ready?” Available to groups of 20 or more, the class offers a basic overview on subjects such as how to put together a portable disaster supply kit, to shelter in place and to make evacuation plans.

The department has taken an even shorter presentation out to a few neighborhood associations, according to Battalion Chief Pucci. The sessions give residents and fire personnel a chance to meet each other and also provide basic, localized information. “We’re trying to condense it even more,” he says, “to hit the bullet points in about an hour.”

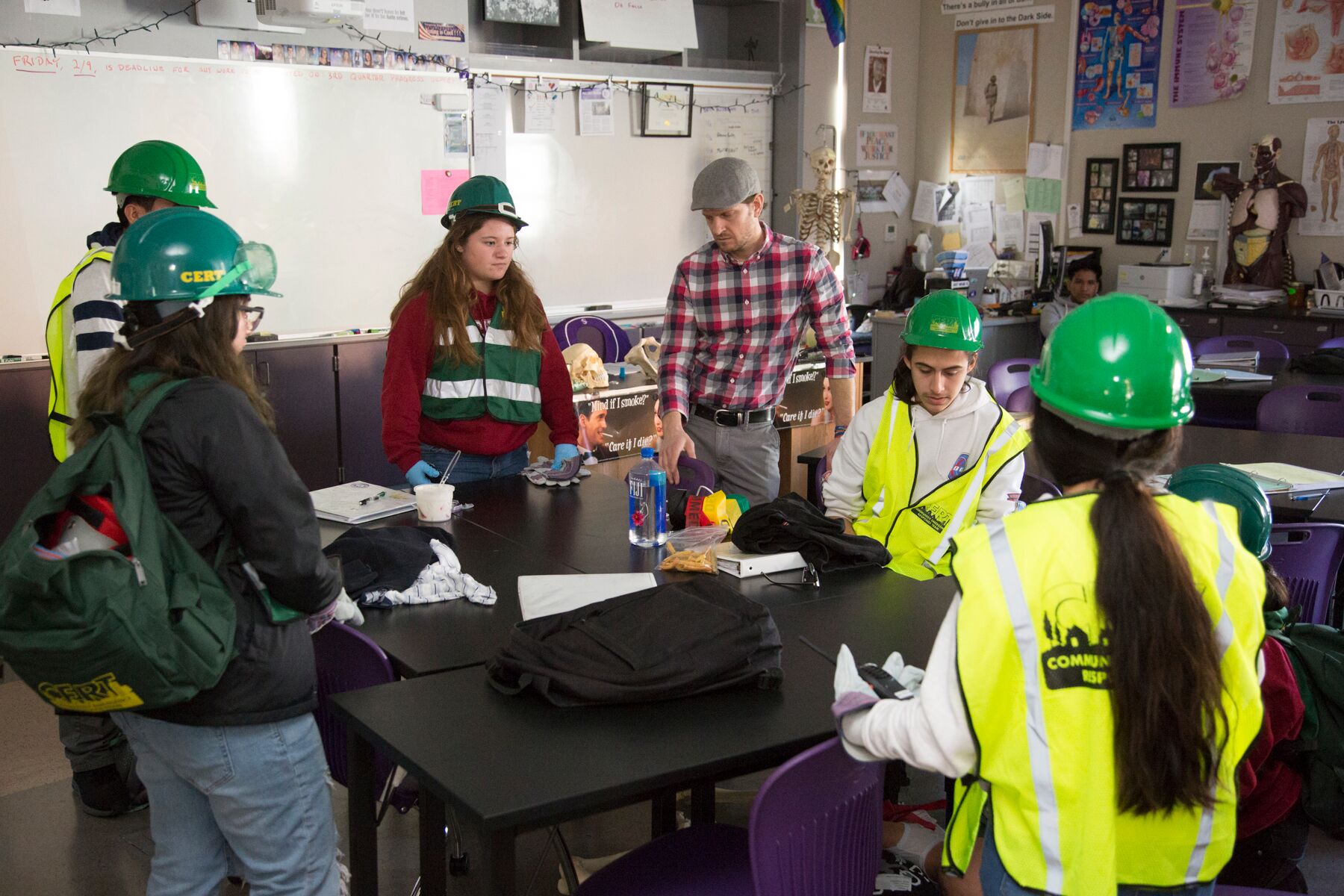

The fire department doesn’t have the staffing to take the CERT course to the schools, but thanks to the cooperation and support of Sequoia High School, CERT training began three years ago to be offered to students enrolled in the health careers academy. Greg Schmid is the current instructor, with assistance from Ashley Gray. They had to get trained so their students could receive CERT certification on completion of the course. About 120 students have gone through the program. Orchard Supply and Redwood City 20/20, as well as several other businesses, partnered last year so each kid could have his own emergency kit.

“It’s pretty empowering to the students,” says Schmid, of all the training. “They’re engaged and they’re super excited.”

Over two days in February, his students got a chance to bring classroom instruction to life during a mini disaster drill, with classmates daubed in “blood,” or buried under chairs, playing the part of victims.

“Ohhhhhh,” the agonized moans sounded through the classroom door. “Momma!”

Axel Mendoza got into the health careers academy on a counselor’s recommendation. He has learned CPR and how to treat injuries, information he finds valuable even though Mendoza plans to be an architect, not go into medicine. “But I can build the hospitals,” he quips.

Alecxa Rodriguez, a junior, was a very convincing bleeding victim with a realistic-looking cosmetic gash to her arm. “I’m in this class because I want to be a plastic surgeon,” she says. “I thought the health academy was right up my alley.” Rodriguez says was able to put her training into practice last summer when a cousin had to be pulled from the water by his uncle. She administered CPR until the fire department arrived. “They teach us very useful things in this academy,” she says.

Her dad, Guillermo Rodriguez, is understandably proud of what she did and thinks the training is “wonderful.” He works with kids at his church and would like to learn some of the same things his daughter has: “It’s important to me because I can help more people.”

With the ravages of last year’s fires all around them, North Bay communities are dealing with the aftermath at the same time as they plan for the next fire season. Mill Valley, whose fire chief lost his Coffey Park home to the Tubbs fire, is looking at tougher fire prevention regulations for vegetation. A new proposal would regulate plants near residences and highly flammable varieties such as bamboo, acacia, cypress and juniper would have to be 15 feet away from the house.

Norris, of the OES, says the idea of “defensible space” is to ensure that trees aren’t growing under the eaves or that vegetation can’t “ladder up” and consume a house. But that doesn’t have to mean bare ground. “There is a very reasonably defensible space that is both aesthetically pleasing but also a firefighter looks at it and says, ‘Okay, that’s a house we can save.’”

At least as big a concern locally, Maupin says, is with a fire starting inside a building near open land and then spreading out courtesy of the vegetation. Though it’s certainly possible San Mateo County could, under the right conditions, be faced with the fires that broke out in Wine Country, aid from other agencies, plus Calfire’s aerial and other resources, would converge to fight fire with firepower.

“That’s one of the things that helps me sleep at night is that I know we’ve got enough of an initial punch to stand a solid chance of taking care of whatever we’re faced with,” Maupin says.

Norris assures people that preparedness starts in small steps but is definitely worth doing. “The vast majority of people survive absolutely every disaster,” he says. “But the ones who are prepared can restore their lives more easily.”

Ready to get ready?