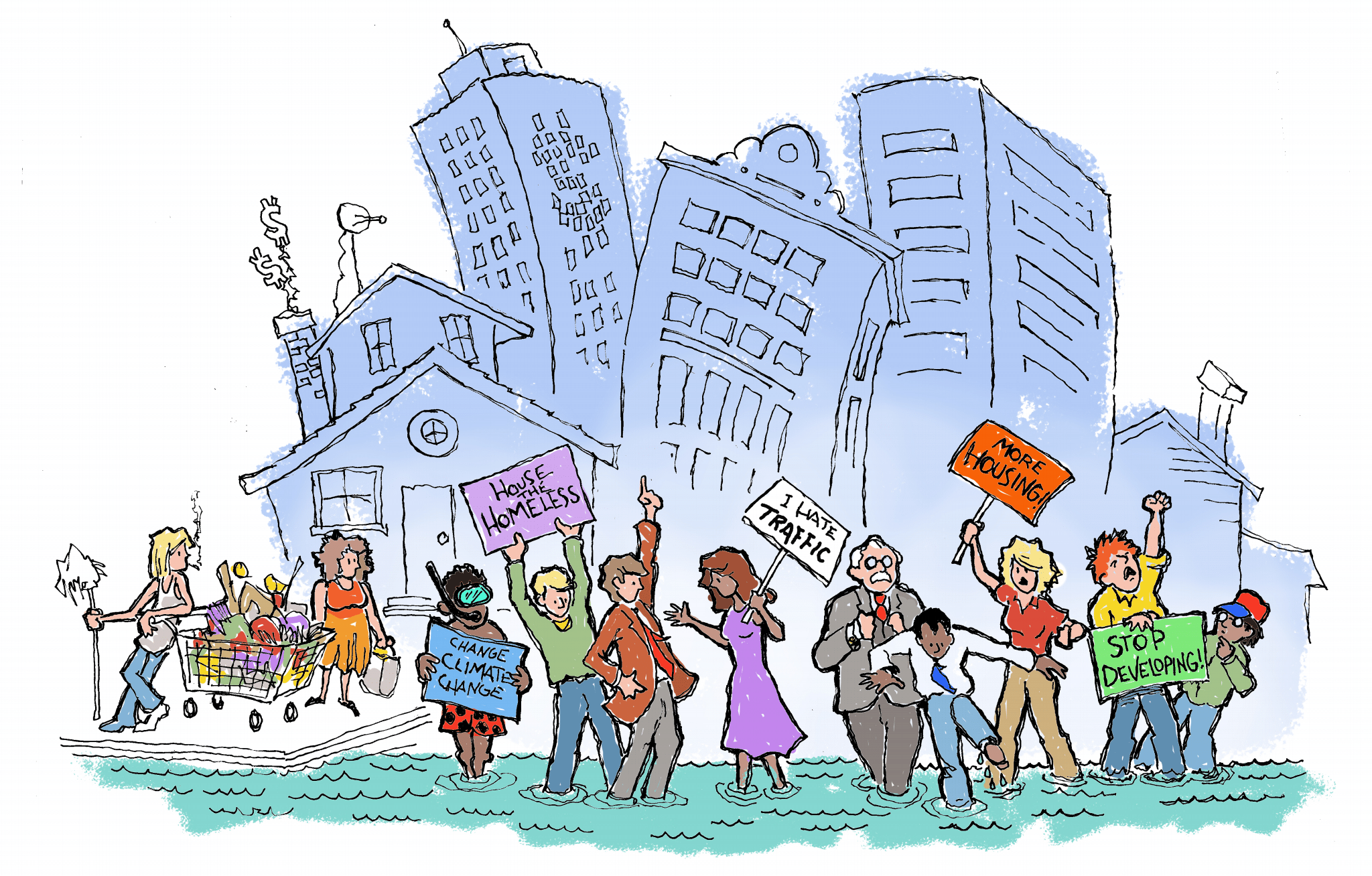

City Council advances gatekeeper process to increase development caps

Council supports allowing developers to donate land to affordable housing nonprofits

At last week’s study session, the Redwood City Council directed to City Staff to continue to advance the gatekeeper process that would increase developments caps downtown.

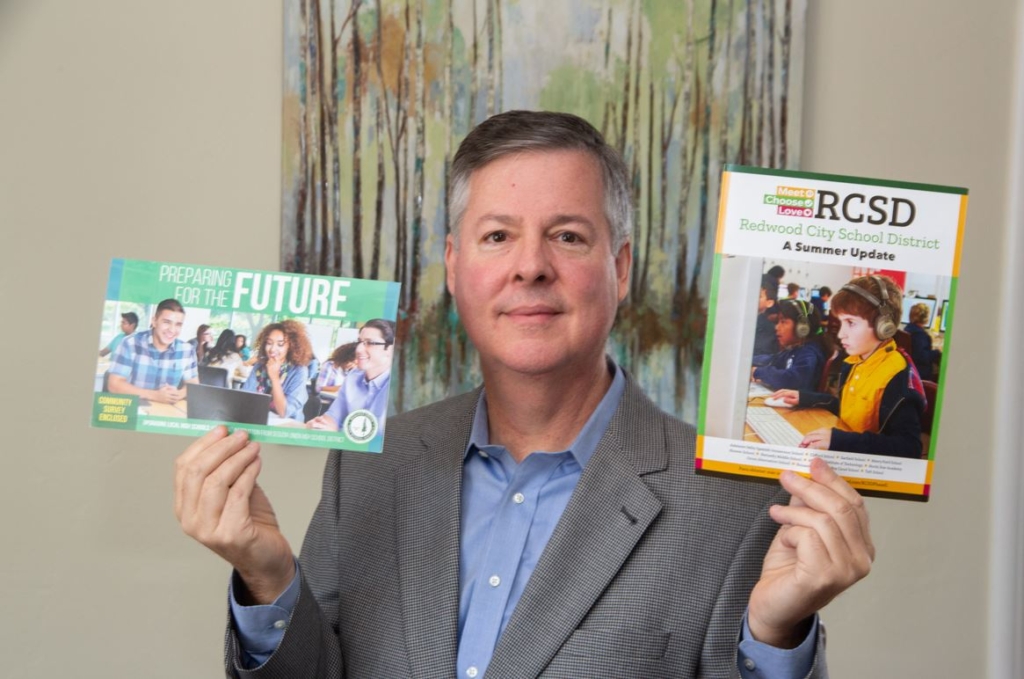

The process, which was initiated in 2020, was intended to provide a framework for screening and evaluating proposed projects that would exceed the square footage limits imposed by both the Downtown Precise Plan and the General Plan. Eight mixed-use project are currently under consideration.

One critical point of the discussion centered around whether to allow projects to meet their housing requirements by donating offsite land to nonprofit affordable housing developers. Half of the proposed projects offered offsite land.

Speakers from Eden Housing and MidPen Housing, two of the affordable housing nonprofit partners, spoke favorably about allowing this option, arguing that the offsite option would allow them to secure better financing options and produce more units at deeper levels of affordability than producing housing onsite.

A majority of the council spoke favorably of granting greater flexibility for the land donation option.

“Bottom line: we need more housing, we need deeper affordability, and we need it to be done as quickly as possible,” said Councilmember Chris Sturken, who represents the downtown neighborhood. “Wherever you can find that property… I am fully supportive of getting the housing built.”

Some councilmembers expressed concern about the so-called “land reverter” options, which would give the City the option to take ownership of the offsite properties should the affordable housing not be developed within a specific timeframe.

But when Councilmember Alicia Aguirre said, “we are not on the business of building homes,” staff quickly clarified that the proposal would give the City the option to acquire the land, but not the obligation. Aguirre later stated she supported the land donation option.

The General Plan and Downtown Precise Plan amendments are due to return to the Planning Commission and City Council in July. The final entitlements and building permits for the eight projects are expected to be granted in 2025.