As efforts were mounted to ban gun shows at the Cow Palace, a proposal was made to wrest control of the aging venue from its owner, the State of California, and turn it over to a local board of directors that included two members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors — and only one member of the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors.

That’s for an arena and event center located in Daly City.

“I was livid,” said San Mateo County Supervisor Don Horsley. “They think San Francisco ought to have some say over this.” Horsley noted that the Cow Palace is owned by the state and located in San Mateo County. Yes, it’s right on the border with San Francisco, but if it was located just across the border in San Francisco, “they wouldn’t ask us (to be on the governing board).”

More than 200 years ago, San Mateo County was part of San Francisco. More than 75 years ago, San Mateo County was San Francisco’s suburb. Forty years ago, Silicon Valley began its emergence as a global phenomenon anchored in Santa Clara County.

Through it all, San Mateo County seemed largely left out, overlooked and in the shadow of a northern city that everyone loved and a southern economic engine everyone wanted. It was the pass-through county, where people lived but worked elsewhere or the place people drove through on their way to somewhere more important, more substantial. To paraphrase Gertrude Stein, there was no there there. San Mateo County was, in the precision of the phrase, a hotbed of social rest.

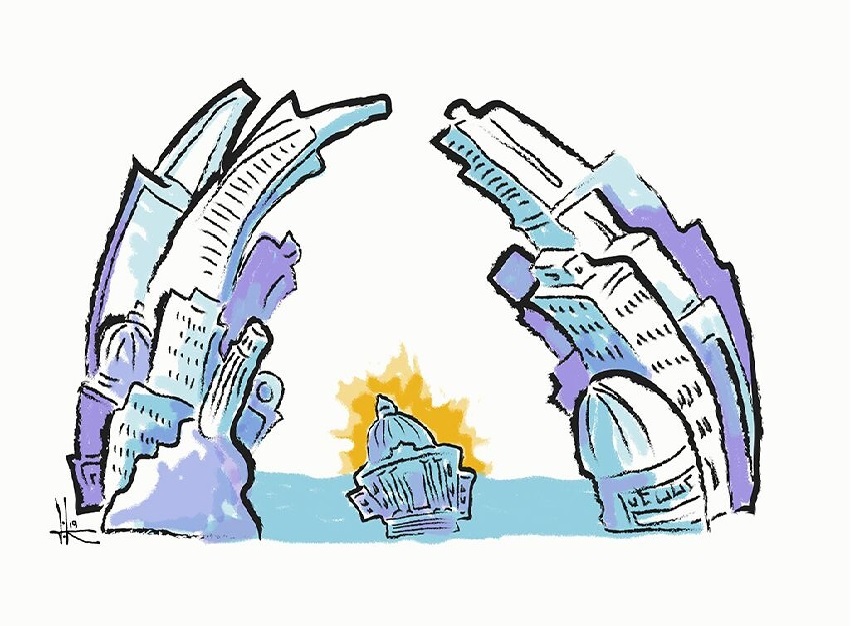

The big cities were San Jose and San Francisco, and they were hungry for prominence and influence and to be a center of regional power. San Mateo County – 20 cities, each one smaller than the next, not one of them more than a fraction of the size of the big cities bookending the county – was the center of nothing in particular. Freeway off ramps, maybe.

All that has changed. San Mateo County has built its own economic engine, a major contributor to state budget sales tax revenues, a major employer, world headquarters to the biotech industry, home to leading tech companies and home to some of the wealthiest people and some of the most expensive real estate in the world. People commute from north and south to work in San Mateo County.

All that has changed, except, perhaps, a broad recognition of all that has changed. As regional forces press for solutions on issues such as housing and transportation – as San Francisco and San Jose press their own agendas on the county – is it time for San Mateo County to assert itself as its own place of prominence and influence and regional power? No longer a “kid brother” in the region, some are saying that San Mateo County needs to confidently take its rightful place as a co-equal at the political table.

That could mean an end to the longstanding way business and politics have been done in San Mateo County, perhaps even a radical realignment of power to give the county a single, unifying and high-profile voice. It could mean consolidation of the county’s 20 cities or the county’s 23 school districts into fewer – even one? — bigger political unit. Perhaps it might be time for San Mateo County to elect its own mayor, someone on par with San Francisco’s London Breed and San Jose’s Sam Liccardo.

“One of the issues for San Mateo County, candidly, is how we perceive ourselves and whether we perceive we have power in the region,” said Rich Gordon, president and CEO of the California Forestry Association. Gordon served as a county supervisor for 13 years and represented the county in the state Assembly for six years. “Since we don’t have a mayor, we’re not a player. Some of that falls back on this as a county. We’re not promoting and affirming our role as a key part of the region. Sometimes we see ourselves as a stepchild. One of the things we have to do is change that internal perception.”

A fourth-generation Californian born and raised in San Mateo County who was on the leading edge of the Baby Boom, Gordon can track better than most the evolution of San Mateo County from the original Native American settlements, to the Spanish rancheros, to the country vacation homes of wealthy San Franciscans and service communities that arose along the train line, to the post-World War II boom that covered farms with subdivisions and waves of homes.

“Growing up in the 1950s, everybody’s dad went to work in San Francisco,” Gordon said. “Now, San Francisco comes to work in San Mateo County.”

In the 1960s, there were clear lines of distinction between each of the cities in the county, gaps in development of housing and businesses that made it easy for well-established residents to tell when they were leaving Millbrae and entering Burlingame or San Bruno.

“The average resident of San Mateo County cannot tell you where the dividing line is between cities. They don’t know the boundaries,” Gordon said. “We are no longer a suburban community.”

It’s a thought embraced by Horsley: “We’re not small-time any more. We’re not even suburbs. We are one urban area from Daly City to East Palo Alto.”

“That is the way we were,” said Gordon, “and in many ways that’s how we still see ourselves. But we’re not. We are part of an urban region, part of a metropolitan region.”

And a powerhouse part of the region.

“Historically, the county has been in the shadow of San Francisco and San Jose, but I think that is changing and I think there is growing recognition of the economic clout of San Mateo County,” said Assemblyman Kevin Mullin, born and raised in South San Francisco. Mullin is speaker pro team of the Assembly, a key leadership position in recognition not only of his own assertiveness but of the county’s economic dynamism. “From the biotech to high techs to the presence of the airport, this is an economic engine that is helping drive not only the Bay Area economy, but keep the state budget in the black,” he said.

One of the county’s great strengths has always been the ability of its political bodies to work together. There are 20 cities and towns in the county – some of them so small they would barely qualify as a neighborhood in San Francisco or San Jose. Even the largest cities are a fraction of the population of the big cities that sit at either end of the bay. Because of this, goes the conventional wisdom, every city has a seat at the table and a chance to assert itself within the county; and county elected officials are better at working collaboratively and achieving consensus.

“Because we collaborate so much, we do get more done,” said former three-term county Supervisor Adrienne Tissier. The former Daly City Mayor also served for 10 years, twice as chair, on the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the body that allocates state and regional funds to transportation projects and programs and to Bay Area transit agencies. San Mateo County always has competed well for state and regional funds and, some say, it’s because the county can put forward a united front when seeking such funds.

Because there is such unity of both purpose and common needs among the cities, the county does insert itself into the critical issues affecting it, Tissier said. This unifying ability to some degree makes up for the lack of a regional identity as a power base. “I don’t think it’s as much of a problem because when it’s necessary, we do insert ourselves,” she said. But Tissier acknowledged that the county’s engagement at a regional level often is reactive, rather than taking ownership from the get-go on an issue rightfully in the county’s purview.

There may not be a more provocative example than the recent regional effort, called the CASA Compact and led by state Senator Scott Wiener, to set requirements for the construction of new housing. Now in the form of legislation authored by Wiener, this effort clearly is aimed at small, suburban cities. Recently, San Jose Mayor Liccardo, in an interview on KQED Radio’s “California Report,” essentially said the Bay Area’s three big cities – San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland – are doing their share to tackle the housing crisis, while the suburbs, meaning San Mateo County, are not.

“The reality of the political calculus is, we know an awful lot of suburban voters already have got theirs. Right? They own their homes. Those homes are appreciating rapidly in value,” he said.

“We’ve got 99 cities and towns in this Bay Area. And right now the three large cities — Oakland, San Francisco and San Jose — are leaning in hard on trying to get more housing built. We’re not going to make progress with just three cities. We need everyone pushing together,” he said.

But when the CASA task force was formed, no one from San Mateo County was invited to serve on it. County representatives since then have been included, and the county’s state legislative delegation has vowed to assure the protection of their constituents’ interests. That said, it’s another example of the county being relegated to the back seat. Elected leaders had to assert the county’s interests, rather than them honored or recognized from the outset.

“CASA no question is being influenced by the big city mayors,” said Mullin. “But in order for anything consequential to happen in Sacramento, they’ll have to have all the legislators from the nine-county Bay Area.”

Still, Mullin acknowledges that some of that the big city officials who are asserting their views regionally need to have a better understanding that the rest of the region matters, too.

“Our governor is a very smart guy and understands that the region was very helpful in electing him, but his perspective is one of a big city mayor. I have reminded him of the fact that there are nuances in the housing conversation when it comes to the urban/suburban divide and I think he will be mindful of that in the future,” Mullin said. Similarly, Mayor Liccardo, who Mullin describes as a good friend, “should understand the politics in San Jose around housing are very different than that of San Mateo County. The key is how do we work collectively as a nine-county region on policies that take into account the differences between San Jose and Burlingame?”

Still, with all the physical and economic growth in the county, for all the collaboration and commonality of purpose, the county was initially overlooked on a critical regional issue that would have affected the nature of its communities and the authority of each city to make its own land use decisions. That authority is just as zealously valued in Burlingame as it is in San Jose or San Francisco.

Some of that regional tendency is historic, based on patterns that hearken back over generations. Some of it is the nature of big cities to think their priorities are, by definition, important to the entire region. It’s the San Francisco Bay Area, not the San Mateo County Bay Area after all.

But there is a growing sentiment among some political leaders that the county can no longer wait for a policy crisis to speak up and needs to adopt a more assertive posture.

“We aren’t good at bragging and there’s a lot to brag about when it comes to innovative approaches to policy,” said Mullin. “We’re not good a touting our own achievements. … We as a county could certainly do more in speaking with one voice to make sure we are helping to lead the region.”

In recent months, these concerns have prompted a specific and bold proposal: Add two positions to the five-member San Mateo County Board of Supervisors, elect six supervisors by district and elect one countywide to a four-year term as chair or president of the board. The proposal was recently advanced by Jim Hartnett, general manager and CEO of the San Mateo County Transit District and a former Redwood City Councilman. The at-large supervisor would have some additional authority over the county budget.

But more significantly, perhaps, this person would be, in essence, the county mayor – the singular leader who would speak for the county.

“It’s a very interesting proposal,” said Gordon. “One of the dynamics for San Mateo County is that we don’t have the same consistency of leadership as San Francisco and San Jose and Oakland. They get mayors elected for four years. The president of the board of supervisors rotates every year.”

Though former County Supervisor Tissier thinks the county already does a good job asserting itself, she finds the idea of a county “mayor” intriguing. “It still covers the entire county,” she said, “and if you have to go to someone, you’d know who to go to.” And Horsley also thinks the idea “has merit. It would be someone who represents the whole county.”

Former County Manager John Maltbie thinks otherwise, however, arguing that the county does just fine on the regional playing field.

“For the most part, if you look at Santa Clara County and San Francisco, there is pretty much a high alignment between the three counties. On any given issue, there may be daylight between one or both of the counties and those things tend to get worked out on a case-by-case basis,” Maltbie said.

The county has been well served by its representation on regional bodies, Maltbie said, citing a long list of county supervisors who have ensured “we get our positions expressed very forcefully in a variety of different ways.

“There’s not a mayor speaking for the county, so there probably is some lack of visibility, but the county is in a news shadow between San Jose and San Francisco and that’s kind of the way it’s always been,” Maltbie said.

“What’s so wrong with the way the county operates?” Maltbie continued. “Look at San Francisco. Our county operates a lot more efficiently. San Jose isn’t exactly an example of one of the best run cities anywhere. I’d say the system of government we gave now works well, I would keep it. If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”

Over such perspectives, countless home improvement projects have been debated:

“What’s wrong with it now?”

“But it could be better.”

“It ain’t broke.”

“Maybe it should be fixed before it breaks.”

Though not as radical as merging cities, changes in the delivery of services have been happening throughout the county. Redwood City, for example, provides fire service for San Carlos, which contracts with the county sheriff for police. A four-city joint power authority, Silicon Valley Clean Water, provides wastewater service for an area roughly from Belmont to Menlo Park. Caltrain service was kept alive decades ago through a partnership between SamTrans, San Francisco County and Santa Clara County’s transit agency.

“We’ve changed who we are, our demographics have changed, we’ve changed some of our communities,” Gordon said. “We haven’t changed our governance. The change will continue to occur. It’s really a question of do we play a role in managing that change or do we let it happen to us as others around us have some impact on us?”

The changes facing the community are hard and challenging, with a seemingly inexorable arrival of taller buildings and greater densities along transit corridors. Meanwhile, communities fight to preserve their essential character and values, including preserving the estimated 70 percent of the county which is parks and open space and will never be developed.

But the changes are coming, Gordon said. “I do think that communities in San Mateo County need to have greater density,” he said.

Maybe it qualifies as an existential crisis, this opportunity not just for inward reflection about what the county’s place in the region should be, but a decision as well to step into the spotlight on a regional stage.

“It is an opportunity for San Mateo County to play a greater role in the region,” Gordon said. In some respects, I think San Francisco is in decline and has its own struggles around its identity and what’s going on in its neighborhoods. And Santa Clara County’s challenge is that it’s a very diverse county, from garlic farms in Gilroy to the Tesla plant.” Add to that, he said, is the challenge of “ Palo Alto being anything except a princess also makes it difficult for Santa Clara County.

“We are more homogeneous,” Gordon said. “We have far better collaboration. We have a great history of working together. I think we should claim a rightful place to help define the region.”

This story was published in the April print edition of Climate Magazine.