Baron Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, the greatest flying ace of World War I, was a legend in his time, and beyond. He was credited with 80 kills between 1916 and 1918, when he himself was shot down over France. He flew many of those missions piloting the Fokker Dr.I tri-plane that he’d painted his favorite color, earning him the sobriquet “The Red Baron.”

But then, he never had to do battle with a five-year-old.

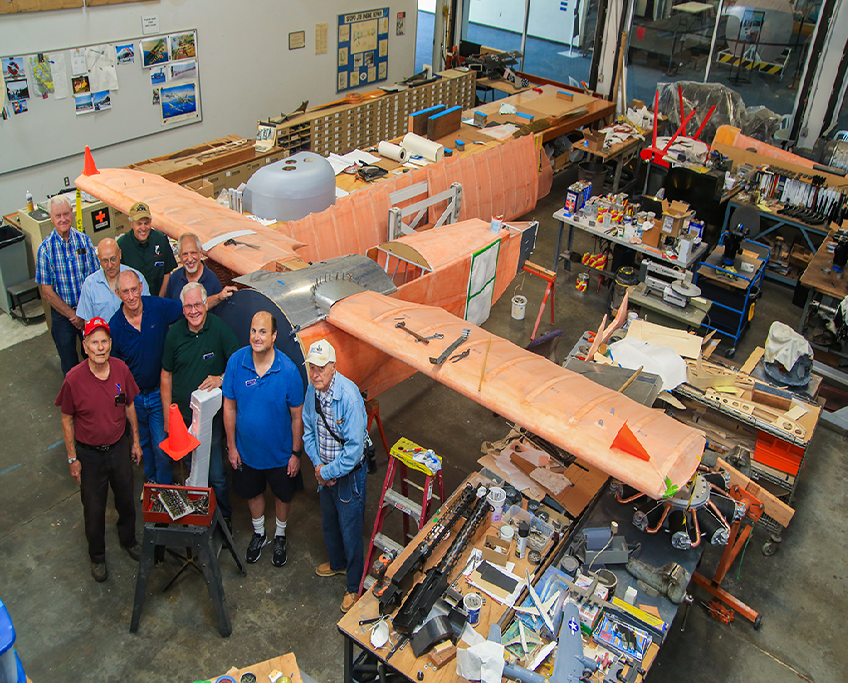

“The experience here in the museum is a five-year-old kid can break anything,” says Mike Fox, one of the team of volunteers at San Carlos’s Hiller Aviation Museum tasked with recreating a static model of the Baron’s signature plane. “But the management here decided they want to allow people to have access to the airplane, to get in the cockpit and move the controls and use it for a photo op. So we had to pretty much kid-proof it.”

Some of the volunteers are former amateur pilots, like Fox, or they were machinists, engineers, or just airplane enthusiasts. Nearly all of them are retired, and like the docents who patrol the hangar-like structure, they come twice a week for the fellowship, and to get their airplane fix.

“I’ve never flown,” says Don Torburn, who has been supervising the team’s model making for two-and-a-half years. “I was mechanical engineer, which probably helped me more than flying.” He started working at the museum about 19 years ago (“That’s longer than any job I ever had”) and manages to make the two-mile commute almost every Tuesday and Thursday without getting on the freeway. He oversaw the building of the volunteers’ longest job to date, the Buhl Autogiro replica that took five years to complete, and as he approaches 90 he is used to the ribbing, and the respect, the rest of the team gives him.

Take the Baron, for instance. The younger-than-90 set may first think about Snoopy, who battled the Red Baron in comic strip and song in the sixties, rather than the actual von Richthofen. To that, Torburn responds, “The Baron and I were buddies.”

The museum, named for the remarkable Silicon Valley inventor and entrepreneur Stan Hiller, is now in its 21st year. Hiller started building ray guns and toy race cars when he was 14. “And then at 17 years old, he got the idea that he wanted to build a helicopter,” says museum VP of Operations Willie Turner. After teaching himself to fly, and several false starts (the 1940s were quite a bit pre-YouTube video), Hiller and his team built the first “Hillercopter,” which he piloted in Memorial Stadium on the UC Berkeley campus.

The original was donated to the Smithsonian, leaving the volunteers to create a replica for the Hiller Museum. That was difficult and time-consuming, but nothing compared to the Buhl Autogiro—which might have been easy for Leonardo. They had to recreate their model through photographs and research, which took about five years. “In that case we had to make the wings, the coach, everything. Because all we had was the cockpit pod,” says Torburn. When it was finished it was appraised at $640,000.

Building the Fokker has been painstaking in a different way. The museum bought the model from Digital Design in Phoenix, AZ, and soon discovered that much had been left to the imagination, and interpretation, of the builders. There were some issues with the propeller, and the machine gun (non-functional, of course). But mostly it was about the details.

Take the wing ribs. They may sound delicious but as any pilot can tell you, they are essential to each wing of an airplane. This was a three-winged airplane, mind you, and each wing rib had plywood webbing in the middle, as well as a plywood cap on the bottom and the top.

“The only parts that came in the kit were the webbing in between,” says Fox. “So we had to form the all the other pieces, and then create a chance to glue them together so that everyone looks like every other one.” His skills are in woodworking so he did more than his share of the gluing, and waiting for the glue to dry. In a six-hour shift, you might get half a dozen ribs done, and when you’re only coming in twice a week and there are hundreds of ribs, the job stretched out over the years.

According to volunteer Dean Williamson, the guys in the shop met with Hiller CEO Jeffrey Bass last year to discuss the fate of the Fokker. “Jeff wanted a time frame and said, ‘When do you think what will be done?’” recalls Williamson. “And one of the guys said, ‘June!’ and Jeff says, ‘Okay!’ Then the fellow turned around and said, ‘But I didn’t tell you which year!’”

Now the volunteers are optimistic that the model plane will be completed by August. “Now we’re getting to the point where we can start climbing the aircraft and hopefully within the next couple of weeks we’ll be able to paint it and start putting it together,” says Williamson.

One of the reasons their jobs take so long is that the men in the shop are always on call to repair what has just been broken. Make a visit to the museum on Skyway Road east of U.S. 101 in the summer, and you’ll see the problem: Scores of kids from summer camps and schools swarm the space, climbing on everything they possibly can and treating nothing gingerly.

“Being a pilot, when you’re flying, you’re pretty gentle on the controls, you’re using one or two fingers and making very small, slow movements,” says Fox. “But when the kids get in the airplanes, or the flight simulators that we have here, boy, they’re slamming those controls up and down the right and left with all the strength they have.”

The Fokker Dr.I is expected to be one of the most loved, and hence highly maintained exhibits in the museum. “It’s a full-time job for the shop doing the maintenance on the other aircraft on display,” says Fox—and this wasn’t supposed to be a full-time job.

“We’ve got the standing joke around here,” says Williamson. “If somebody wants to go on vacation, take a day off or something we always say we’re gonna have to dock their pay.” Williamson first came to the museum when he was inspecting the property as a member of the Redwood City Fire Department, where he worked for more than 28 years. After retiring he was invited to work there as a volunteer, and has been there ever since.

Turner says the museum will build a whole display around the Fokker, putting the plane in context, describing dogfights and World War I itself. What they have learned at the museum over the years is that most people don’t know much about anything that they are seeing.

Take their replica of the plane the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk in 1903 (the original hangs also at the Smithsonian). “We figured everybody knows the story about the Wright Brothers,” says Turner, a former pilot himself. “We’ll move on from that. And it turns out people don’t know the story of the Wright Brothers. That’s one of the greatest inventions known to mankind. So we said, ‘Well, we’re an aviation museum, we better tell that story.’”

The Wright Flyer, as it’s known, is just a stone’s throw from another replica: Spaceship One was the first civilian aircraft to go into space, in 2003—on the hundredth anniversary of man’s flight.

“We let people go in and sit in the cockpit, pull the switches to, play with the controls,” says Turner. “Most museums don’t let you do that, especially in an artifact like that; they don’t want you to get in it because you’re going to break something. And people do, things break all the time. That’s when the guys in the shop go out there and fix stuff.”

This story was originally published in the August print edition of Climate Magazine.