News that a replica of World War I German flying ace Manfred von Richthofen’s blazing red triplane was being built in San Carlos triggered recollections of the city’s brush with another famous flyer from the “war to end all war” – Eddie Rickenbacker, dubbed America’s “Ace of Aces.”

Note that Rickenbacker’s claim to fame has the qualifier “America” attached to it. Von Richthofen, whose plane has been brought back to life at the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, was credited with 80 kills between 1916 and 1918 when he was shot out of the sky over France. Rickenbacker had 26 kills, but it must be pointed out that the United States didn’t enter the war until 1917. Still, that’s a pretty impressive record for such a short time in the deadly skies of the Western Front.

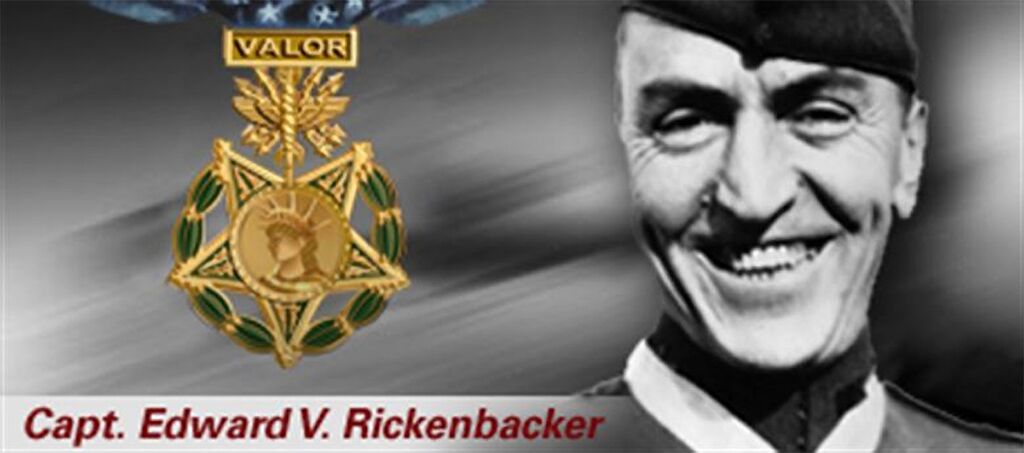

Rickenbacker, who was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his combat exploits, lived an impressive life in many fields. He was a self-made man who blazed trails in the early days of auto racing as well as aviation. He set a land speed record of 134 miles an hour in 1914 at Daytona and went on to buy the Indianapolis Speedway. He also brought an airline, but it was his survival skills that captured the admiration of the public. Not only did he escape death in World War I, his luck continued on to World War II when he spent 24 days and nights floating in a rubber raft after the bomber he was on crashed in the Pacific on an inspection tour.

Rickenbacker’s local connection came in 1921 when he flew across the nation, a flight that started in Redwood City on May 26 and ended two days later at Bolling Field in Washington D. C., a record-setting transcontinental venture that covered 3,000 miles, according to the Air Force website. Rickenbacker wrote about the flight in his autobiography called simply “Rickenbacker: an Autobiography.” The flight was made in a DH-4, a two-seater British biplane, actually a couple of them. The DH-4 he took off in at Redwood City was a “cannibalized” version of one that he crashed earlier in Los Angeles.

In his book, Rickenbacker said he “planned to make my official start from San Francisco” but the field at the Presidio “was not long enough to take off with the (fuel) load I had to carry to get to North Platt, Nebraska – my first stop.” The Redwood City Standard for May 26, 1921 said his decision to take off from Redwood City made the San Mateo County seat “the center of interest in aviation circles on the coast.” The newspaper report said Rickenbacker told reporters Redwood City’s airport offered the best spot for a plane hauling a ton and a half of aviation fuel.

In his book, Rickenbacker said he took off twice from Redwood City, once at 4 a.m. when he ran into thick fog and “almost took the top off Goat Island in San Francisco Bay. I hurried back to the field and waited until 8 a.m. for the fog to clear.” Another local newspaper, the Times-Gazette, also lauded the Redwood City airport’s advantages, particularly after his plane crashed in Wyoming on the first lap of his flight. Rickenbacker made a “landing on a poorly laid out field.” His plane was wrecked and the newspaper blamed ditches that surrounded the Wyoming airstrip. “Rickenbacker, having arrived late at night did not see them and dashed into one.”

Captain Rickenbacker actually took a mail plane to Chicago – riding “the mail bags” was the term used then – where another DH-4 was ready for him, according to an account that appeared in the Redwood City Tribune in the 1970s that said he flew that plane to Dayton, Ohio, where he replaced it for the last leg of the flight to the capital. There was at least one report that the final leg to Bolling Field in Washington, D. C., was in a Junker – a German aircraft.

A detailed story about the recreation of the Fokker fighter plane flown by the “Red Baron” appeared in the August 2019 issue of Climate (and online here).

This story was published in the March print edition of Climate Magazine.

Photo credit: U.S. Air Force