Even non-historians know that history repeats itself. “There is nothing new under the sun,” as the wise King Solomon purportedly put it. “Been there, done that?” Well, who hasn’t? So about the last person who should have been surprised by Mitch Postel’s recent deep dive into local history for a magazine article was Mitch Postel.

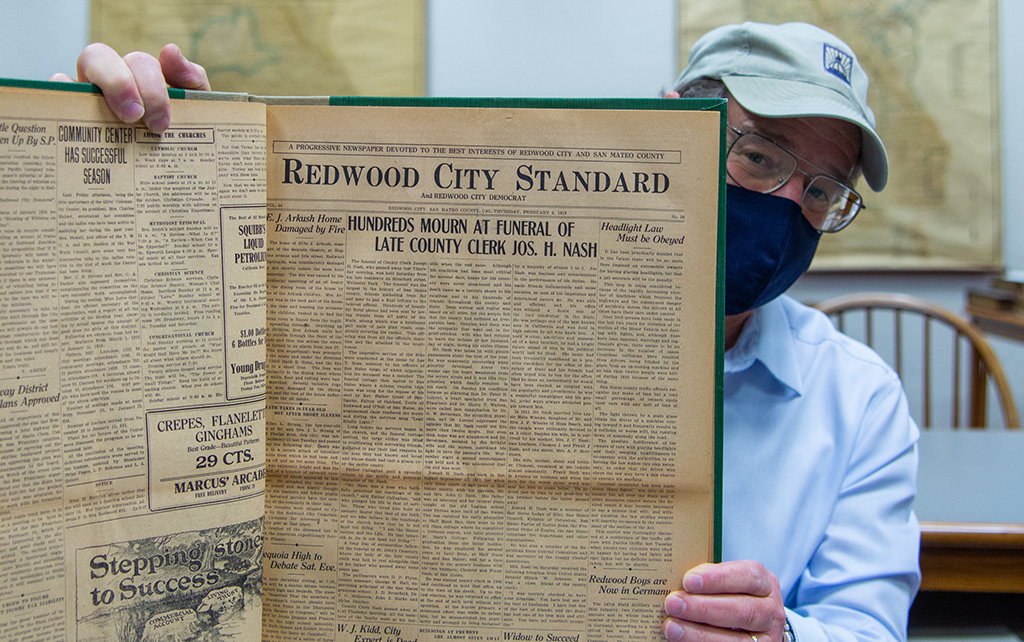

Yet there he was, the president of the San Mateo County Historical Association, sheltered in place at home because of Covid-19, researching the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919 —and colliding with an astonishing, positive case of déjà vu all over again, right out of Yogi Berra’s homespun lexicon.

The century-ago masks and mask-makers. The curfews and quarantines. Schools and churches closed. Flipflopping health orders, varying by city. And, in time, rebellion against mask-wearing and all the other restrictions. A coronavirus carbon copy. And Postel, of all people, surprised by history.

“Yes,” he agrees with a laugh. “I was just getting hit with it constantly,” he adds, of the then/now parallels he kept finding. “…When I started doing this (I thought) ‘Oh well, this was so many years ago and attitudes have changed so much and it won’t be the same.’ And it turns out to be almost exactly the same. I was really flabbergasted that people have not changed that much.”

Stuck at home because of the Covid-related closure of the downtown Redwood City museum and its satellites, Postel had just buttoned up a lengthy treatise on turn-of-the-century polo in San Mateo County. The story was to have appeared in the summer issue of the historical association’s magazine, La Peninsula, which is available to association members, some libraries and for sale at the museum gift shop. But members of the publication committee thought since Covid-19 made the Spanish flu more topical, he should switch gears and write about influenza first.

Menlo Park’s WWI Camp

When the United States got involved in World War I, Menlo Park became one of 16 mobilization and training camps in the nation. Camp Fremont was established there in July 1917, and more than 27,000 soldiers eventually lived in the sprawling installation that stretched from El Camino Real to the foothills. (At the time, San Mateo County’s entire population was about 36,800, not including the military.)

Postel knew Camp Fremont would be part of the story of how the Spanish flu impacted the county, but after it emerged with deadly effect in September 1918, cases were by no means confined to the base. The first camp death was recorded Sept. 28, the same day the U.S. Public Health Service issued a report on “a very contagious kind of ‘cold’ accompanied by fever, pains in the head, eyes, ears, back or other parts of the body.” Though symptoms supposedly would disappear after three or four days, sometimes pneumonia set in and patients died.

October was the worst month both for the soldiers at Camp Fremont and residents of San Mateo and San Francisco counties, Postel writes. Although it was apparent across the nation that a health emergency was in progress, 150,000 patriotic Northern Californians gathered in Golden Gate Park to show support for the soldiers fighting in Europe in the final Allied push.

By early October a strict quarantine was declared at the camp, and Palo Alto began requiring residents to wear cheesecloth masks. Meanwhile, cases were showing up in cities, including 153 in San Francisco and 500 in Los Angeles. By mid-month, conditions at Camp Fremont continued to deteriorate, with 164 patients critically ill and only 25 nurses available.

Concerned about Camp Fremont, Redwood City’s health officer Dr. J.D. Chapin quarantined 12 residences as a “precaution” and ordered public gathering places closed. Only a week later, victory seemed to have been declared: The Redwood City Democrat newspaper reported that the Sequoia Theater and schools could be reopening as a result of a rapid decrease in new cases.

Not Really Over

Later in the month, however, new cases had jumped to 149, for a total of 250 altogether, including seven fatalities. The city trustees adopted a resolution calling for all residents to wear masks and the police chief was approaching citizens “without gauze” to advise where they could get a mask.

Newspapers devoted space to each illness and death. In the pre-Hollywood era, members of “the smart set” were celebrities whose clubs, parties and travels were followed assiduously. Prominent people began to catch influenza and die, among them the superintendent of two mosquito districts in the San Mateo/Burlingame area who was the son of a well-known, long-time ranch owner. Just 28, he left a wife and baby.

San Mateo’s health officer ordered schools, churches, theaters, clubs, lodges and pool rooms shut down. Burlingame did the same. Only manual arts classes in the San Mateo high school district could continue; students were filling orders for emergency surgical supplies for U.S. troops in Siberia.

The death of a member of the pioneering Parrott family was particularly upsetting. After serving overseas in an ambulance unit, Joe Parrott spent only six months at home before volunteering to go back to the infantry. After a brief bout with pneumonia, he died at the Camp Fremont hospital.

“He was a legitimate hero and just to enlist in the Army as a private from this big classy important family is kind of amazing to me,” Postel says.

Despite Parrott’s death, the San Francisco Examiner reported that the Camp Fremont quarantine had been lifted. Most soldiers could leave the base. Meanwhile, up in Hillsborough, San Mateo and Burlingame, masks were required on penalty of a $100 fine and 20 days in jail.

A Mask Revolt

The flu rolled up new San Mateo victims in the prime of their lives: a 44-year-old painter, a 38-year-old housewife and a chauffeur. Mask-sewing brigades sewed away. Though initially acquiescent, mask-wearers in time began to resist, especially in San Francisco, and police there started hauling “mask slackers” into court by the hundreds, Postel says. “An anti-mask league was formed and rallies were attended by the thousands.”

The mask-or-else edict came down San Mateo Countywide in late October. But by November, despite some contradictory evidence including more deaths, newspapers were reporting a falloff in cases and that the epidemic was coming under control.

“By December of 1918, many in the San Francisco Bay Area believed, if not entirely eradicated, influenza was a decreasing problem,” Postel writes. “That and the euphoria caused by the War ending [Nov. 11, 1918], resulted in a lessening of attention by local newspapers to the epidemic.” They started calling it “pneumonia” instead of “influenza.”

In fact, the flu continued its dread harvest locally until at least February 1919, though the one newspaper minimized the disease as “old-fashioned grip(pe),” nothing new. Closures of schools and public gathering places were intermittent; many parents just kept the kids home.

Summing up the trajectory, Postel says, “Around the middle of September, people were starting to get the idea that there was a problem. And then October was horrible. Well, by mid-November, people had had it. You know, ‘The crisis is over, I’m taking off my mask. This has got to be it.’ And then of course there was a spike in January. And then putting back on the masks and taking the kids back out of school, that became really politically difficult.”

World War I with all of its privations was over. Thousands turned out for a Feb. 22, 1919, welcome home celebration in Redwood City. About 40 San Mateo County residents had died in the war, compared with 131 taken by the flu by December. But many people were just tired of it.

Heroines of the Flu

In his research, the big surprise to Postel was the heroic response of women volunteers through two emergent Red Cross chapters who stepped up to help wherever needed. The San Mateo County chapter provided over 61,000 gauze compresses, 1,900 face masks, 4,400 pairs of socks, and 3,400 sweaters, plus more than 400 “pneumonia jackets” (used either to warm patients or to cool them through tubes inside the jackets.)

The women raised more than $118,000 and organized a “motor corps” to transport victims and ferry supplies. At mortal risk of coming down with the disease themselves, they delivered food and cleaned houses for victims too sick to cook or clean.

One remarkable society woman, Cecelia Cudahy Casserly, converted her Hillsborough mansion into an emergency hospital for three weeks. At 1 p.m. Oct. 23, her furnishings began to be moved into a cottage on the grounds. Later that night, “Casserly Hospital” took in its first four patients.

“I think it’s rare in history that you have moments like that,” Postel observes, “that there are that many people who are so altruistic that they’ll step forward and help others. … We were really picking up statewide notice because of the activities that were going on here.”

The Progressive Era ethos that people should take responsibility for their community was an influence on these motivated women. Progressives, Postel says, saw value in government marshaling everyone behind the war effort and in applying expert opinion to combat influenza. “Doctors were saying things like wear face masks and don’t congregate in large parties. Close your movie theaters, close your schools. Do all the stuff that’s really repugnant,” Postel says. “Still is today. All the things that we rebel against today, people were rebelling against then.” People got fed up with government telling them what to do.

Despite being closed since March and losing both revenue and visitors, Postel concludes that “as much as I hate to admit it, a lot of the restrictions we’re facing now are probably necessary.” Rest assured, though, that the history of the 21st century pandemic isn’t being overlooked: People are being asked to submit their own Covid-19 stories and observations to www.historysmc.org— what they did, what they missed, what they learned as a result of the 2020 pandemic and so forth.

Surprising or not.