The Facebook post laid it out there:

“There’s no end to the evils of the Republican Party. Not working for the people of the country, working for their own pockets. Disgusting! And the few friends I have that are Republicans, keep your mouths shut if you ever want to share a meal with me again because I am so over this bulls—t!”

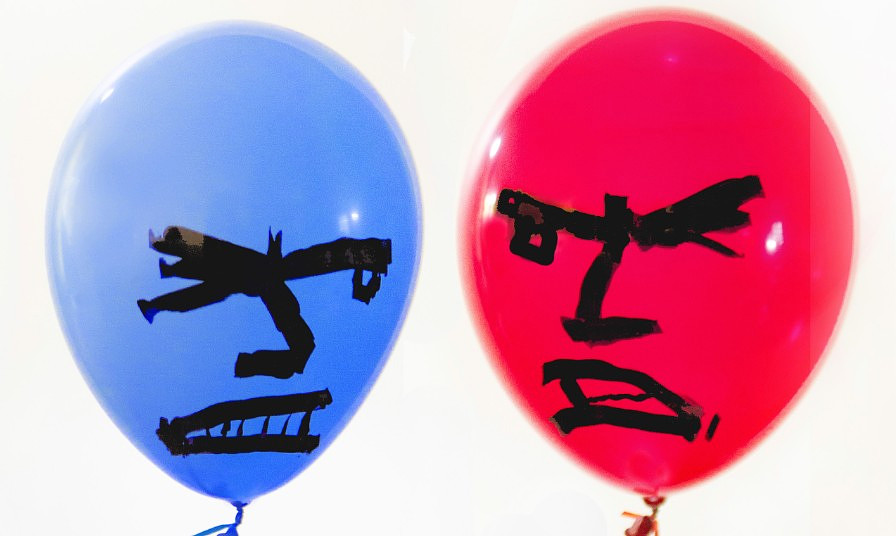

It’s a distressingly familiar scenario, with both liberals and conservatives spewing volumes of venomous rhetoric – and not just on social media but in venues ranging from debate halls to dining rooms and college dorms. It may not be true that the country is more divided than ever; those in their sixties recall the violent decade of the same name, and the nation lost more than 600,000 lives during the Civil War. Still, with the coming of both the 2020 election and the often-tense holiday season, people increasingly want to know, “Why can’t we talk with each other anymore?”

Perhaps it begins with perceptions. The chair of the San Mateo County Republican Party, Christina Laskowski – who is Filipina – says when people discover her party affiliation, they automatically assume she’s a racist. Emily Bender, a San Carlos singer and voice teacher, is a liberal Democrat. She’s also gay. In her experience, political discussions with conservatives quickly become personal and threatening. She says, “There’s definitely a way in which it feels like people on the right think of me as less of a person because of being gay and being a woman.”

Name-calling

Perceptions can quickly turn into nasty, simplistic labels and dehumanizing stereotypes. In Redwood City, Russian-born attorney and real-estate broker Maria Rutenburg says her support of Donald Trump has earned her epithets including, “Putin whore,” “Nazi” and “anti-Semite.” (Rutenburg is Jewish.)

More escalation follows. Disagreements that begin as simply political or philosophical devolve into emotional battles between good and evil. And that’s when friends, colleagues and family members stop speaking to one another.

Two local experts agree, however, that long before people stop speaking, they’ve already stopped listening.

The Rev. Warren Dale, co-founder of the Peninsula Conflict Resolution Center and current pastor of First Church of Redwood City, says people are often so intent on proving their point that they refuse to let in an iota from the other side. Moreover, he says, they frequently seek refuge in strong positions through a fear of losing closely held values or, worse, their own humanity.

“How do I protect myself from you either discounting me, disrespecting me, attacking me, or even stripping me of that which I value and that which defines me?” Dale asks. “People retreat to those positions, and the anger goes up to the point where it even becomes hate.”

Dr. Robert Navarra, a licensed marriage and family therapist in San Carlos, links the decline of conversational civility to the “Four Horsemen” of failed relationships, as described by emeritus psychology professor John Gottman of the University of Washington.

Those four elements — criticism, defensiveness, contempt and stonewalling – often drive vicious arguments about politics and other sensitive subjects. Navarra, a certified Gottman therapist, explains that criticism departs from a mere disagreement and attacks an individual (“only an evil person could think that”). Defensiveness – the natural response to criticism – revs the engine louder. Next, contempt introduces belligerence, sarcasm, mocking and a smug sense of superiority; Navarra calls it “the single-biggest predictor” of a failed conversation and, ultimately, a relationship. Finally comes stonewalling, a psychological and physiological shutdown in which people lose the ability to think and converse coherently.

Getting personal, rather than focusing on the issues and listening to the other side, causes discussions to deteriorate rapidly. Navarra says research at the Seattle-based Gottman Institute, co-founded by John Gottman and his wife, Julie, shows that “if there isn’t a self-corrective mechanism in the first three minutes, the conversation will end badly.”

Taking a Timeout

How to kick in that auto-correct? Navarra recommends hitting the pause button and focusing on what one needs in a situation, rather than engaging in an ad hominem attack.

“There’s a huge difference in the trajectory of a conversation,” he says, “when it moves from a description of the other person, which is typically criticism or contempt, to saying, ‘Here’s what’s important to me and why I think this is something that should be addressed.’”

Beyond stating one’s own position, Navarra and Dale agree it’s even more important to understand the other person’s point of view. That takes a willingness to listen and probe, even when the other side’s convictions are deeply held or may seem repugnant.

“That’s a difficult position to take when you think or feel that the other person has such strong feelings that they may never listen to you,” Dale says. Nonetheless, he continues, it can be done, especially when one listens from the point of view of an impartial third party, and asks questions that explore beliefs and experiences rather than rebut arguments.

Especially vital, Navarra adds, is the ability to see the similarities – both good and bad – between oneself and the other side. When that happens, he says, “you’re not coming from a place of superiority. It’s an emotional leveling of the playing field, as opposed to saying, ‘You’re an idiot for thinking differently from me.’ The key, ultimately, is that you don’t state your position until you can adequately describe the other person’s position.”

A feeling of moral superiority often fuels disparaging comments and opinions, even among people who think of themselves as tolerant and broad-minded. Elizabeth Sloan, who considers herself a political progressive and belongs to the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Redwood City, in 2017 delivered a reflection that challenged other members to

“Over the years, inside these walls, I have heard individuals and groups denigrated and demonized in ways that seem completely antithetical to our Unitarian Universalist values,” Sloan told the congregation. “Republicans, George W. Bush, (former defense secretary) Donald Rumsfeld, (former vice president) Dick Cheney. Mormons. Christians. Sean Hannity. Fox News. Donald Trump.

“I’m not talking about strong criticism, which we’re allowed,” Sloan continued. “I’m talking virulent, corrosive dismissal of people as people, as not worthy of our regard. And – this is the really insidious thing – a blanket assumption that if I attend church here, I must feel the same way.”

Feeling Isolated and Fearful

In the overwhelmingly blue Bay Area, conservatives often report their colleagues and families express both astonishment and dismay when they find out people they presumed were liberal actually lean right. Laskowski says that on discovering she was a Republican, one family member even “physically started to react, like he was going into shock.”

As a result, many conservatives go underground. Rutenburg isn’t one of them; in July, she asked to create a “MAGA” mural beside the “Black Lives Matter” that the City of Redwood City had allowed another resident to paint on Broadway. The city responded by eliminating the “Black Lives Matter” message. The incident made national news, and sparked controversy throughout the community.

In an email, Rutenburg says, “I’ve had countless people approach me and tell me that they support and admire me, but they cannot do so publicly, as that would mean they would have to leave the Bay Area. This extreme intolerance for anything short of ultra-liberal views has created an atmosphere of cultural terror for a very sizable political minority in the Bay Area. Putting an American flag on your house is considered an act of heroism. People call me to say, ‘I came out; I put a flag up,’ as if they were on a suicide mission.”

It cuts both ways. Daisy Segal – Pastor Gary Gaddini’s administrative assistant at Redwood City’s Peninsula Covenant Church – holds views that many might consider contradictory; she’s both a liberal and an evangelical Christian. That sometimes puts her in tricky situations.

“I’ve had conversations with fellow congregants who have assumed I was Republican, and have gone down a path of tearing down things that I believe in,” she says.

For certain people, such comments would demand a response. But Segal usually refrains.

“I have a hard time confronting people about things like that,” she admits. “I generally just try to change the subject.”

Staying Silent

Keeping quiet about contentious topics is a conscious strategy not just for Segal, but for many, including San Carlos businessman Peter Hartzell.

Hartzell’s business interests include a manufacturing facility in the Central Valley town of Tracy. When it comes to prevailing ideologies, the city of more than 82,000 and the Bay Area might as well occupy different planets. Hartzell, a strong liberal, nonetheless keeps his opinions to himself around the factory floor.

“There’s just a line that you don’t cross,” Hartzell says. “And as long as you stay on this side of that line, everyone’s very civil. Everyone wants to talk about why the A’s lost the game last night, and family affairs and this and that. But you don’t bring up politics. And you don’t bring up religion.”

Asked about his willingness to engage in self-censorship, Hartzell says of himself and his co-workers, “I think we all do. We’re employees together. We’re part of a team. We’re trying to get important things done for this business. And there’s no benefit to picking scabs. I mean, there’s some light teasing. But, frankly, it’s too serious for much teasing, at this point. And so we stay focused on the work to be done.”

Staying mum can also be a useful tactic for everyone at the holiday dinner table – especially, as Mountain View environmental activist Bruce Karney observes, “when there’s been lots of wine.” Karney, his wife, Twana, and their Midwestern relatives (around equally split between liberals and conservatives) have agreed to avoid subjects such as politics and climate change.

Still, divergent opinions are inevitable in public, if not private, life. Earlier in the decade, Karney’s friend, former Mountain View Mayor Ken Rosenberg, established Mountain View’s Civility Roundtable Discussion Series. The events aimed to get quarreling residents out of their neighborhood associations’ Internet chat rooms and into a forum where they could meet face-to-face and talk more amicably about their differences.

“You’re looking at your neighbors, and you have an opinion, maybe a strong opinion,” Rosenberg says of the meetings. “But now you’re confronted with the reality of decorum and social graces and proximity … You just have to behave differently. And I think the opportunity to be heard for what your opinion really is, as opposed to just attacking (another) person for being wrong, only exists in person or a very successfully moderated online chat group.”

Social Media’s Role

For better or worse, social media is where billions of people exchange information, ideas and serious trash talk. As one person recently posted on Facebook, “Life is short; be sure to spend as much time as possible arguing on the Internet about politics with strangers.”

Many believe it’s that stranger factor – the relative anonymity of the Internet – that emboldens people to shoot from the lip. (Others question that; Rosenberg says Mountain View residents still talked churlishly online even when they had to divulge their names and the streets where they lived.)

What seems certain, however, is that written communication lacks the richness of face-to-face conversation. In an oft-cited study, UCLA emeritus psychology professor Albert Mehrabian found only 7 percent of a message was conveyed by words alone. Tone carried 38 percent, and body language and facial expression, 55 percent. Consequently, the worst possible place to make a point – especially a sensitive one – might be an email or a social-media post.

The Internet and social media are also where people increasingly get the bulk of their information. Frequently, it comes from ideological soulmates, through “shares” of opinions or news feeds that promote an already agreeable viewpoint. “Clickbait” – the arousing teasers that lure people into a story – often attempts to horrify or outrage readers from the start. Throw in fake news or half-truths calculated to get a rise, and little wonder people get angry.

Through sophisticated algorithms that track users’ online activity, search engines may even be delivering various versions of the same topic, on the basis of the viewer’s presumed attitudes. For example, the recent film, “The Social Dilemma,” showed two searches for “climate change” – with the same provider – that yielded different results apparently designed to appeal to the user’s beliefs.

When even computers become sycophants, people find it harder to get opposing opinions. They also become confident of their convictions; after all, they’ve done their homework, and they’re convinced they have the facts.

But the full set of facts can be hard to come by, even in the mainstream media. Most networks and newspapers tilt their coverage toward the political tastes of their audiences. And research shows that the most extreme readers and viewers on both sides now tend to get their news mainly from the sources they agree with.

In a 2014 study titled, “Political Polarization and Media Habits,” the Pew Research Center concluded, “When it comes to getting news about politics and government, liberals and conservatives inhabit different worlds.” Pew researchers found 47 percent of conservatives relied on Fox News “as their main source for news about government and politics,” and that 88 percent trusted Fox News. For liberals, NPR, PBS and the BBC were the most-trusted sources.

Getting the Whole Story

But if Americans are becoming more and more narrowly informed, the full picture was what Hartzell and his Redwood City friend, retired attorney and fellow liberal David Vallerga, wanted when they struck out for Racine, Wisconsin, and environs in 2017. The northern half of the state had been pivotal in President Trump’s victory the previous November. The two men wondered why a traditionally blue state had recently turned red.

Both Hartzell and Vallerga say they went mainly to listen, rather than express their own opinions. With one exception – an encounter with a combative Republican politician – they describe their talks as cordial and often warm.

“Listening is powerful,” Hartzell says. “It’s powerful for the listener, and I think it was powerful for the people who we listened to.” Adds Vallerga, “It all boils down to one word and what flows from that word, and that’s ‘respect.’”

San Carlos City Council member Laura Parmer-Lohan finds “empathy and respect” essential in serving the town’s 30,000 residents. She adds that she ran for the council in 2018 in part “because I observed at the time, and still do, that people on opposite sides of the political spectrum are divided, and that many are in pain and feel excluded and unheard.”

In addition to – and connected with – the death of George Floyd, that sense of being “excluded and unheard” may have created the flash point that ignited the unrest of 2020. In the words of retired Rear Admiral John Bitoff, a San Francisco resident who speaks frequently about civility, “We all desire to be treated as worthwhile human beings.” When that doesn’t happen, it’s unsurprising that people become alienated, cynical and ultimately violent.

But, Bitoff says, mutual respect and congeniality can keep communication and productivity flowing, even between ideological adversaries. The late Supreme Court justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg were close friends, despite their sharply differing legal philosophies. And in a commencement address at Suffolk University Law School in Boston, political columnist and television commentator Chris Matthews described the fruitful relationship in the 1980s between Republican President Ronald Reagan and the Democratic Speaker of the House, Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, Jr.

“Ronald Reagan and Tip O’Neill fought like cats and dogs all day and could still be friends at night,” Matthews observed. The two political veterans, he said, “were always trying to get along, even though they were 180 degrees opposed.”

How to Get Along

So there it is – once again, that plaintive appeal from Rodney King in 1992: “Can’t we all just get along?” Whatever the outcome of the election, Segal, the liberal evangelical, thinks it will be hard.

“We will definitely need a healing process,” she says. “I think all leaders in companies, in religious institutions, and especially in the government – we are going to need them to call people to come back together as a nation.”

Whether it can happen is anyone’s guess. Following the unexpected election of Donald Trump in 2016, crowds rioted and chanted, “Not my president!” even as the outgoing Barack Obama attempted to soothe the nation by saying, “We are now all rooting for his success in uniting and leading the country.”

In the end, it all comes down to Americans as individuals. Can people set aside their differences, or at least agree to address them civilly? Or will this Thanksgiving, Chanukah and Christmas provide settings for yet more slammed doors, raised voices and shattered wine glasses? One can only hope for the former. But if it’s the latter, then the country’s post-holiday hangover may last longer than most.