More people are moving out of San Mateo County than moving in, a trend that significantly accelerated during the pandemic, U.S. Postal Service change-of-address data suggests. And yet, the real estate market in San Mateo County is as hot as ever.

“I have been doing this for nearly 20 years in SMC and I have never seen an influx of buyers like we have had over the last 180 days, especially over the last 90,” said Bob Bredel, co-founder of San Carlos-based Dwell Realtors.

A 4,000 square-foot Emerald Hills home initially projected at $4.7 million recently sold for over $5.5 million within seven days, said Vicky Costantini, who runs Compass along with her son, Enzo. According to the 16-year real estate veteran, “We couldn’t price it high enough.”

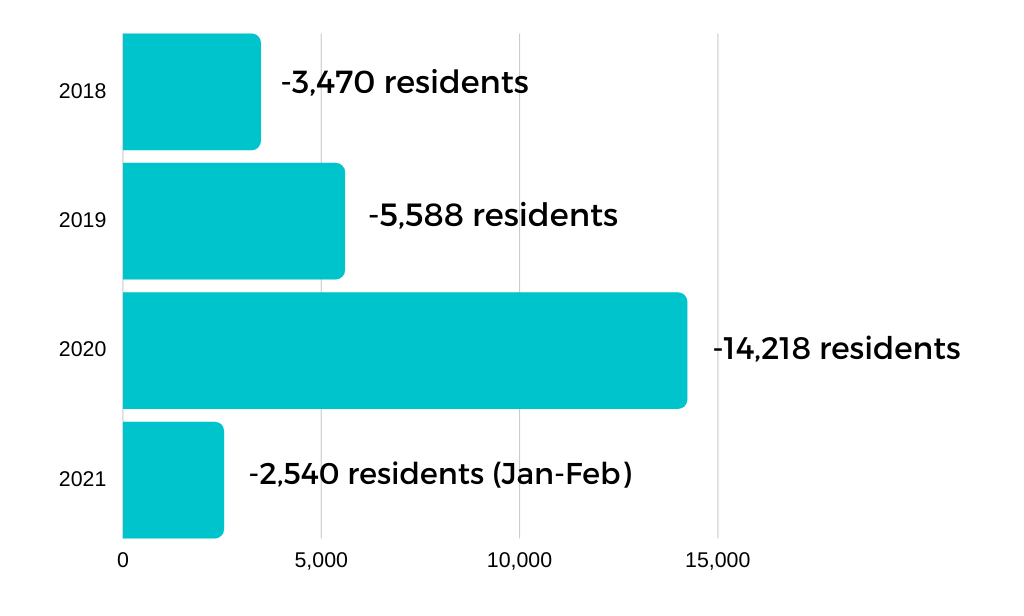

The sizzling local home market appears at odds with ongoing migration patterns. In 2018, 70,717 residents permanently changed their addresses to zip codes outside the County, while 63,244 changed theirs from out-of-County locations to zip codes within the County, a net migration loss of 3,470, according to U.S Postal Service data. The data suggests the net loss increased the following year to 5,588, then accelerated during the pandemic in 2020, when it shot up to 14,218, with 84,068 leaving the County and 69,850 moving in.

The data also suggest the pace of exodus isn’t slowing. In the first two months of this year, the County has experienced a net migration loss of 2,540, nearly matching the net loss for all of 2018, according to the data.

Of course, change-of-address data don’t paint the full migration picture. For one, some people don’t notify USPS when they move. And while the data points to an ongoing exodus, the demand for real estate in the County remains strong, particularly for single-family homes. In March this year, the median price of a single-family home in San Mateo County was $1.985 million, according to data from the California Association of Realtors, which is $235,000 more than in the same month the previous year, and $375,000 more than in March 2019.

Buyers wanting a better deal can look toward the multi-unit market, which “has gone way down” due in part to the pandemic’s impacts and rent control, Constantini said. Rents are down about 30 percent and vacancies are up about 15 percent, which then affects the sales price of multi-unit properties, which is down about 12-20 percent depending on the building, she said.

“Another factor is renovation costs are through the roof,” Constantini said, with spikes in prices on lumber and other building materials making buildings that need work “the toughest to sell currently.”

And yet, the market for single-family homes remains through the roof. A low inventory of homes doesn’t adequately explain the phenomenon, Bredel said.

“We have had low inventory in really every year since 2013,” he said. “The prime difference this year is the number of buyers stacked at each house. They are stacked 10 and 20 deep at each new listing. All well qualified and serious.”

Bredel wonders how many people want to move to San Mateo County, but “can’t because they are being outbid on every house or are simply stalled on their housing search.”

“My feeling is this number is as high as it has ever been,” he said.

To better understand migration patterns, one must also look at who are moving in, who are leaving and for what reasons.

Costantini describes many single-family home buyers as young tech workers in their 30s, graduates of top schools like Stanford and UC Berkeley, some working for companies that recently went public.

“They are all coming in with cash, quick closes, zero contingencies,” she said.

Bredel suspects one of the larger pools of new citizens in the County is former San Francisco residents.

“There is no doubt in my mind that many folks gave up the city to have a yard, community, parks, etc, that were more accessible,” he said.

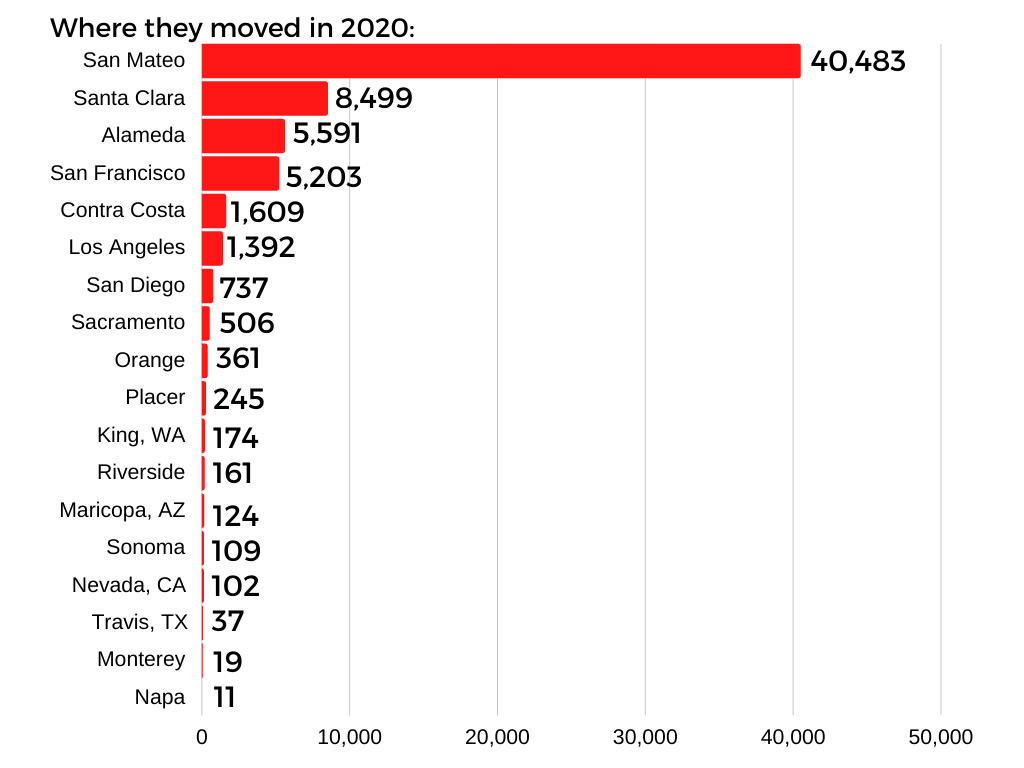

Costantini echoed Bredel’s observations and added that many of those deciding to move out of San Mateo County may also be families desiring more space and other quality-of-life improvements. While much has been said in national media about Californians leaving Texas for political reasons, migration patterns suggest that the large majority of those departing San Mateo County remained in the state.

San Mateo County’s middle-class homeowners are being drawn to communities that are less expensive, have less crime and better schools, Constantini said. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the trend, in part due to worsening of quality-of-life conditions and the rise of telecommuting, she added.

“The regular middle-class family are finding themselves extremely equity rich,” she said. “In Rocklin (Placer County), they can have pool, huge yard…it’s like Redwood City 16 years ago except brand new.”

With geographical limitations on building in San Mateo County, Constantini says she doesn’t see an end to rising prices, albeit there may be fluctuations. That means the influx of young wealthy technology workers will likely continue.

“They’re doing a lot of good things as well,” Constantini said. “What I hope is that they improve our schools” and “give something back to the community.”

Photo credit: Getty images