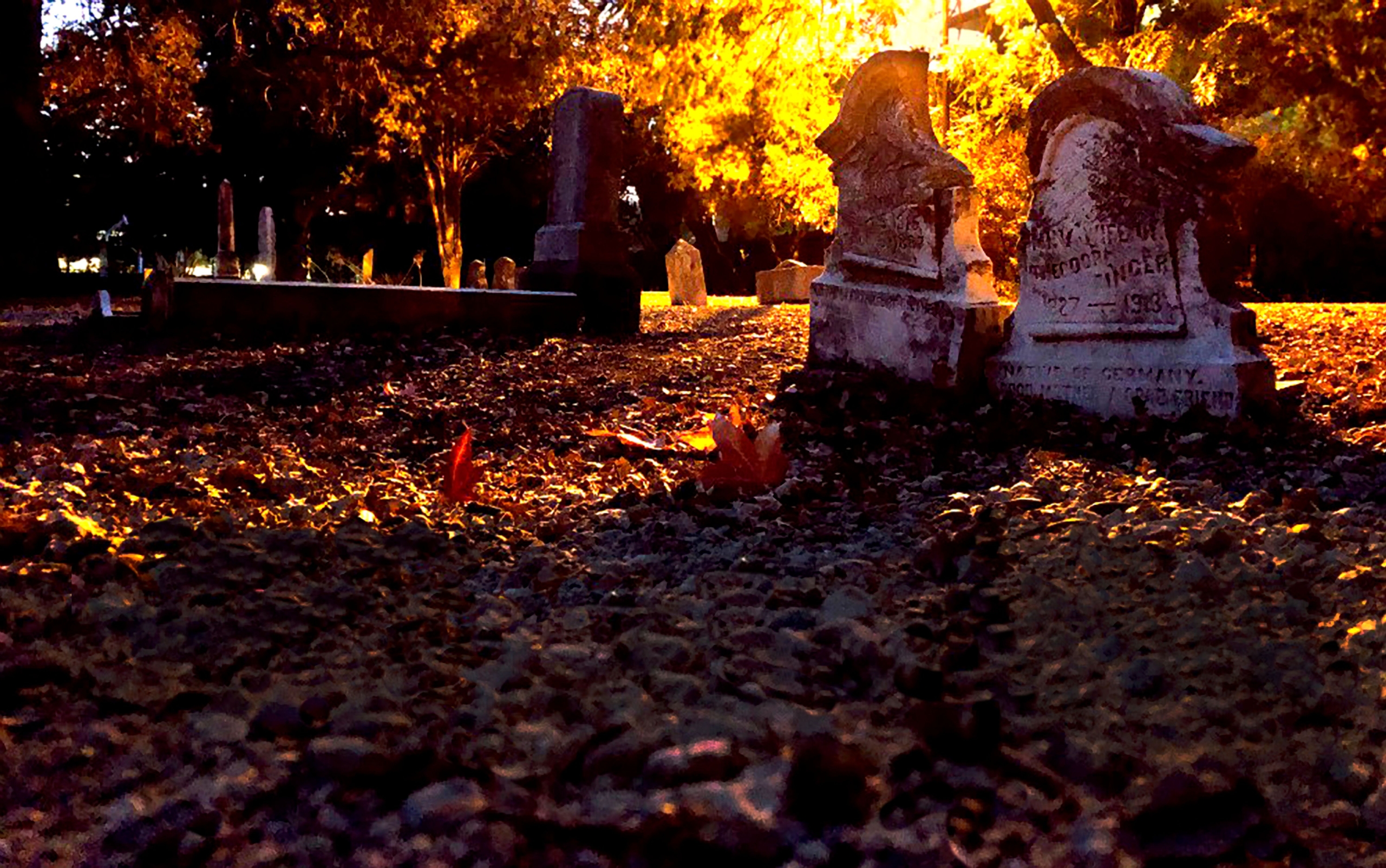

Death, actually, does not us part, solemn marriage vows to the contrary. “Darling we miss thee,” the grieving parents of Willie Bullivant, age 1, lamented on his headstone at Redwood City’s Union Cemetery. That was in 1904. Yet even today, those raw words chiseled in granite reanimate a little life lost like so many in this area’s pioneer days — a baby boy “resting” in a “cradle grave” aside 4-year-old brother Georgie; taken, too, five years before.

The historic Union Cemetery was the first cemetery association in the state of California, and it served early settlers of Redwood City, Woodside and the vanished lumberman’s village of Searsville with a place to bury their dead. Some of the names are still recognizable — on streets (McGarvey and Finger in Redwood City; Starr Road in Woodside), or places (Lathrop House and Cooley Landing in East Palo Alto.) Some of the dead still have relatives to remember them. But it’s an effort of research to “bring back” most of Union Cemetery’s 2,400 buried souls and their stories —business owners, elected officials, a prominent suffragette — let alone tannery workers, laborers or those in pauper’s graves.

That’s just a part of the work performed by a group of community-minded volunteers determined that Union Cemetery be not a clichéd “final resting place” but a living monument to the individuals who began San Mateo County more than a century ago. For decades, the six-acre cemetery was itself dying of neglect, trashed and vandalized repeatedly. (At one point, the city even considered turning it into a neighborhood park where kids could play baseball.) These volunteers and those before them deserve much credit for resurrecting the forlorn property as a state and national historic landmark—and maintaining it as a source of civic pride.

“You walk around and you know these names all over town,” says Jean Tomassi, 81, one of those volunteers responsible for the cemetery’s revival. “It’s like it’s part of history.”

A Sign of Respect

Kathy Klebe, president of the Historic Union Cemetery Association, joined the board several years ago, in part to honor those like Tomassi and her husband, Don, “who worked so hard to get the cemetery back to the way it is. I think that deserves a lot of respect, as does the history of Redwood City. It’s really fascinating when you delve into those people and what this town gave to the state in terms of resources, wood and such.”

Those who are up on their Redwood City history know that the rough-and-ready port town came into existence to serve the fledgling lumber business in the aftermath of the Gold Rush. By 1858, more women and children were joining their husbands in the southern part of San Mateo County, and a need developed for a burial ground, writes John Edmonds, a retired sheriff’s deputy who is an authority on Union Cemetery.

At first, people were buried on property in the general area of Sequoia High School which was owned by Horace Hawes, a state senator. He was leasing it out, and when it came back into Hawes’s control, people were indignant that he wanted the bodies relocated. Tempers cooled a bit when he contributed a substantial sum for a proper burial ground.

City fathers got together and in 1859, the site of Union Cemetery was selected. People could purchase plots for $10 and up, and the first of 13 bodies exhumed from the Hawes property was that of Annie M. Douglas, who had died in March at just 4 years, 4 months. Her small stone, Edmonds writes, stands in the middle of the cemetery next to her brother, who died very young as well.

The Union Cemetery Association operated from 1859 to 1918, though it was still used by local undertakers. During the Depression, Edmonds says, many of the county’s poor were placed there. It may or may not be urban legend that when Woodside Road was widened in the 1960s, some of those pauper’s graves were paved over. The last official Union Cemetery burial was in 1963.

Distressed Property

When the association was formed, the property was deeded to the governor of California and his successors as eventual trustees. The state didn’t turn out to be much of a caretaker, and local newspapers were full of stories about the periodic trashing of the untended cemetery: tombstones knocked over, monuments beheaded and, some suspect, carried off by family members for safekeeping. People were outraged when an iconic Civil War statue was vandalized again and again. In 1962, the city accepted a quit-claim deed from the state, which was happy to get rid of the albatross.

Still, it took years before major improvements occurred. Jean Cloud, a proper but determined lady; Nita Spangler, the outspoken wife of the publisher of the Redwood City Tribune; the late Helen Graves and Jim Munro; Edmonds and others devoted themselves to getting the cemetery cleaned up, documented and restored. In 1983, Union Cemetery was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Among the improvements the city made about 30 years ago were the installation of perimeter fencing which helped reduce vandalism; and irrigation, drinking fountains and lighting. The entrance was relocated to Woodside Road, with paving and curbs and gutters for parking. The parks department works in tandem with the nonprofit Historic Union Cemetery Association, which was established in 1992. Today, says the department’s Assistant Director Lucas Wilder, vandalism and graffiti are infrequent but quickly addressed. Weed abatement is unending.

The department still has about $30,000 allocated to Union Cemetery’s upkeep, as well as for restoration projects, including repairing or replacing damaged headstones. Occasionally family members surface with money to restore gravesites. HUCA has about 80 members (an annual dues increase was just approved, from $10 to $25) who also contribute funds. V. Fontana & Co. of Colma produces the etched grave markers at a greatly reduced cost.

Every year, HUCA forces spend hours weeding and trimming, especially the rose bushes planted throughout the cemetery. Klebe’s husband, Roy, who is part of the gardening brigade, says his goal is to keep all the bushes pruned back for visibility, which helps deter vandalism. “We all feel like it’s because it’s obvious that somebody is taking care of it, we feel like people are more respectful of it.”

Years back, volunteers invested untold hours surveying the site, mapping the burial plots, documenting grave markers and fleshing out the stories of those resting under Union Cemetery’s soil. Current Vice President Ellen Crawford virtually camped in the Local History Room at the library sleuthing out obituaries and other documents, such as the burial logs kept by Coroner James Crowe. A trove of information she posted —from old area maps to the names of those in public graves—is on HUCA’s website (historicunioncemetery.com.)

Lives Cut Short

Some of the news stories are strangely unsettling, such as that of a watchman who worked at Searsville. He took his clothes off every day after work to shower in the spray of the lake’s dam. One day he slipped and fell down the dam; his body was found later. “They called it ‘The Fatal Bath,’” Crawford says.

The death in 1867 of Capt. David Jenkins gnawed at her. The 47-year-old father sailed off to San Francisco in a sloop two days before Christmas, with his son, 13, and some friends aboard. A terrible storm came up and all drowned, but it was weeks before the bodies washed ashore. Jenkins’ wife, Mary, was frantically advertising in the paper, offering a $100 reward. “’Please if you know anything.’ And finally they figured it out,” Crawford says. “It’s a really sad story. But this really got my attention.” The tombstone honors their “sacred memory.”

Some of the pioneer deaths testify to their time. James Bannon, 52, known as “Mountain Jim,” fell asleep in a barn after a drinking bout in 1901, and sacks of oats shifted and smothered him. Peter Hanson, 82, who’d worked on the river and then farmed, died in 1908 of “cancer of the face.” Death claimed 4-month-old Albert Bennett in 1907 of “tuberculosis of the bowels.” Jennie Bomberg, 22, “a popular young lady of cheerful disposition,” died an excruciating death in 1910 after her clothing caught fire. She’d had a cold and was warming some sweet oil and turpentine over a fire when it exploded.

Diseases like typhoid and diphtheria swept through families; the Palmer plot is a grim example. The La Honda couple lost two children in infancy, and four died of diphtheria right before Christmas 1886. Only a daughter, 15, who was staying elsewhere, survived. In later years, she and her husband ran the San Gregorio Hotel.

Union Cemetery sustains the memories of scores of individuals who made a mark on local history. There’s James Pease, said to be the first man to raise the flag in San Mateo County. There’s county Sheriff Joel H. Manfield (RIP 1897) and George Washington Tallman, the county’s first peace officer killed in the line of duty (1888). His monument, which vandals had taken, was replaced in 2003.

Simon Mezes, a lawyer who helped the original Mexican land grant owners secure legal rights to their land, was for a time buried at Union Cemetery. There are monuments for Superior Court Judge George H. Buck, and Benjamin Fox, who took an active role in the county’s creation. Henry Beeger, scion of the Beeger Tannery family, is at rest there, as is “Shingle King” Sheldon Purdy Pharis, who at the time of his death (1884) employed more than 1 percent of the county’s workforce.

Restoring Monuments

Among the replacement monuments is one for the family of noteworthy early photographer James E. Van Court. Last fall a new marker burnished the standing of Sarah Wallis, who was the first woman to head a suffragette organization in California.

Most of HUCA members are “seniors,” if not outright elderly, and board members look for ways to get younger people interested and involved. There’s an annual photography contest open to local students. Boy Scouts sometimes do volunteer projects. HUCA offers free tours, too, and Kathy Klebe would like them to happen monthly, once the Covid restrictions ease.

But the highlight of the year is a well-attended Memorial Day observance featuring speeches, music and costumed reenactors. The focal point is a rectangular plot designated for the fraternal organization called the Grand Army of the Republic, honoring the men who fought for the Union in the Civil War. It’s Redwood City’s Arlington. And towering above it, a 7-foot-tall bronze replica statue of a Civil War soldier, which was first erected in 1869.

For the second year in a row, there’ll be no Memorial Day ceremony this year, but the volunteers will place wreaths on the GAR graves and plant flags. A bagpiper will sound at some point during the day, and at another time, Crawford will get out her piccolo and play martial music.

“I don’t know,” she says of what motivates her, “it’s more for the people who are dead than for the people who come here. But it’s Memorial Day, and I’d like to do something.”