Deny climate change? Can’t. Wishing away big government bureaucracy? Won’t happen. Think you have no fish in the fight over salmon? You’re invested.

You drink water.

Life’s need to replenish corporeal water is a struggle against an absolute limit. There is no new water. A dinosaur guzzling pond water 60 million years ago could have been the first to use the water flowing from today’s tap. Because of that absolute limit, nature imposed the first imperative of water consumption: reuse. What went into that dinosaur also came out, flowed downhill, mingled, evaporated, rained down, ponded and started the cycle all over again.

A more complex version of this limit regulates Redwood City’s water consumption. A bureaucracy established and expanded over more than 100 years and a warming climate add their twists.

Expert opinion is that Redwood City’s water supply probably will be adequate for the next 20 to 25 years. Or maybe not, if the state wins the fight over San Joaquin River salmon habit. Or not, if climate change accelerates. Experts also agree that the city’s supply system is reliable, even in a major earthquake. Small comfort. It’s the supply that is uncertain.

Water Recycled

One thing is beyond dispute: water reuse is coming. It’s only a matter of time until Peninsula users, including Redwood City, will be drinking Hetch Hetchy water that at some point has made its way through a wastewater treatment plant.

Redwood City’s water supply is 100 percent dependent on the City and County of San Francisco’s Hetch Hetchy water system.

Gunplay often settled water wars in years past, but Hetch Hetchy was established by a legislative settlement, resolved in 1913 when President Taft signed the Raker Act. The act gave San Francisco rights to build O’Shaughnessy Dam in Yosemite National Park and take water from the river that fills and flows from it, the Tuolumne. It gets any amount of water flow greater than 2,400 cubic feet per second for part of the year, anything more than 4,000 cubic feet per second for the rest, usually late spring and early summer. Senior rights holders, the Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts, get the first 2,400 and 4,000. That’s still true 108 years after the Raker Act.

Nearly 300 miles of pipeline deliver about 220 million gallons per day of Hetch Hetchy water 140 miles to the San Francisco Peninsula’s Crystal Springs watershed. San Francisco sells some of that water to cities and water districts along the way, who then retail it to customers. In the Bay Area, 26 retailers buy and resell San Francisco water to serve 1.8 million users. Redwood City buys some of this water and resells to about 24,000 local customers.

The setup grants perpetual, and irrevocable water rights to the retailers. Redwood City has an ironclad guarantee of 10.93 million gallons per day.

This is the structure of the Regional Water System, the spigot from which the water flows. Several dozen state agencies from the Governor to the Resources Secretary down to a squad of local agencies have their hands on the controls to protect the system and its agreements.

To keep information comprehensible and comparable from agency to agency in such a vast system, the state Department of Water Resources requires all water retailers except the smallest to file water management plans and update them every few years, each agency addressing the same issues and answering the same questions in similar format. Redwood City’s and San Francisco’s plans informed much of this account.

Planning Ahead

More than just plans, these documents look out and ahead 25 years, crystal-balling what water demand and supplies may look like mid-century. That is just about the point at which Baby Boomers and Gen-Xers—those who grew up with and sustained a water system, from source to wastewater treatment, that was underfunded and built far too cheaply—will hand it over to millennials, who already know they will have to deal with climate change that may threaten species survival.

There is a growing unease among those entrusted with water resources that the traditional planning approach — study and plan for years before reporting — is not keeping up with climate change. In other words, change is happening so quickly the tools currently don’t exist to accurately characterize what’s happening.

San Francisco’s water boss, the Public Utilities Commission, recognized this phenomenon after commissioning a supplemental “vulnerability” study of the Hetch Hetchy system. Released just last month, on paper it stressed the system with 18 temperature rise and climate scenarios that produced more than 1,300 “elicitations,” results that included the best guesses of experts in various fields.

It tested Hetch Hetchy and the upper Tuolumne with temperature rise up to 5 degrees Celsius and precipitation decrease up to 15 percent below “normal.” International agreement is that irreversible global warming occurs when average global temperatures rise 2 degrees Celsius. Sierra snow already melts 15 to 20 days earlier than it did 30 years ago. The study showed that this effect will accelerate as precipitation decreases and temperatures rise.

Snow Turning to Rain

It also showed that the lower mountain snow line will retreat to higher elevations, meaning that the traditional long, slow, steady release of snow melt will be replaced by immediate rainfall runoff. Flooding and overtopping of reservoirs become an increasing possibility.

This happened already at Moccasin Dam on March 22, 2018, when inflows exceeded “unimaginable” flood flows and floating debris destroyed part of the dam, similar to the emergency spillway damage that shut down Lake Oroville the year before.

The study revealed that drought is more than a passing phenomenon whose arrival is unpredictable. Drought also causes more drought.

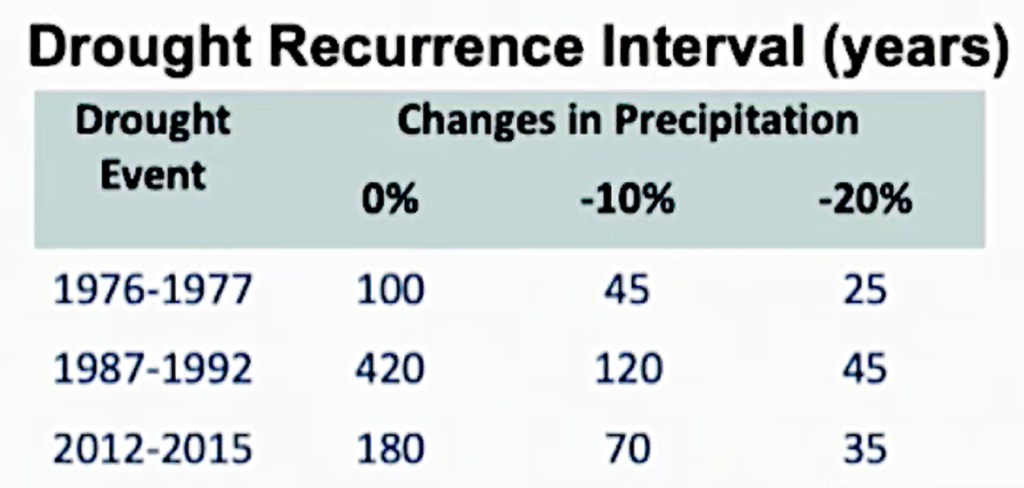

The chart in the middle of this page looks at three historic droughts and shows how much more likely it is that a similar one will recur, given set levels of precipitation. If precipitation remains the same in the Hetch Hetchy watershed, probability says a drought as severe as the 2012-15 event will happen again in 180 years. Cut precipitation by 20 percent and it’s likely to happen in 35 years.

There are other ways to reduce water supply than wait for Mother Nature to do it. People can. As the state has done by producing the Bay-Delta Plan.

Fish Vs. People?

California’s Department of Water Resources, to the satisfaction of environmental and fisheries groups and the discomfort of water users, has ordered that the three tributaries of the San Joaquin River—the Merced, the Stanislaus and the Tuolumne—maintain an average 40 percent of historic river flow to protect salmon and other fish of the Bay Delta.

That would not hurt under normal circumstances, but, if implemented as planned next year, one dry year will require regional water users to ration, cutting retail customers’ water use possibly by up to 20 percent.

Lawsuits, including some filed by the regional group of water retailers of which Redwood City is a part, have held up implementation.

The dispute is now in fitful diplomacy stage, but negotiations are not going well. “In their plan,” said Steven Ritchie, assistant general manager for water of the SFPUC, “they make it sound simply, like, ‘if we just restore 40 percent of unimpaired flow to the river, that will be good for fish, and we should just go with that.’

“But then every time you try to pin them down on that, it’s ‘maybe you might be able to move the water around other times and that might be beneficial.’ How that happens is not clear. Just more water would be a good thing, is what they really come down to saying.”

The uncertainty has forced the SFPUC to do more planning and predicting for the benefit of its water retailers.

Trading Water

It has issued a backup two-tier water allocation schedule if Bay-Delta is implemented. Projecting to 2045, this plan appears to have found that water users may be able to use legal options to make deals among themselves to bank or shift around enough water to make up the shortfall if water supply is reduced up to 20 percent. More than that and the users’ guaranteed supply may go out the window, not so ironclad nor perpetual as first believed.

As CEO and General Manager of the Bay Area Water Supply and Conservation Agency, Nicolle Sandkulla is the representative for the 24 SFPUC water users, like Redwood City, who buy San Francisco water.

She advocates for balance between fish and people. “We are the region in the state with some of the lowest per capita rates of water consumption,” she said. “Customers have continually committed through their water rates, through their own expenditures, to water efficiencies that resulted in historic low water use as we enter this current drought.

“That speaks to the region’s interests, but it also speaks to the fact that, at some point, how much more can we cut it? We are getting to what they call in the water industry ‘hardened demand.’ It’s not quite as easy to save 20 percent when you’re using 50 gallons per person per day.”

Those numbers fit Redwood City just about right. Across the city among all residential users for all purposes, including landscaping, Redwood City currently consumes 99 gallons of water per person per day. Narrowing the focus to a single user’s average indoor potable water residential use, the average consumption is 48 gallons per day.

To help visualize the statistic, consider an individual Redwoodite weighing 175 pounds. At current rates, that person consumes more than twice their body weight in water per day. Cutting water use by 20 percent for that person is roughly the equivalent of losing nearly 80 pounds.

Cleaning Up Wastewater

To return to nature’s first water imperative, the likely next step to backfill water supply when stocks run low or demand goes up is wastewater reuse. It’s a human-centric conceit to call the source wastewater because people have only used it once. Water is water if all the dreck and dross it collects through its cycle is subtracted, just as the natural cycle of evaporation and condensation does.

Redwood City’s water treatment facility is Silicon Valley Clean Water at the end of Radio Road on the Bay shore. It removes 97 percent of the dreck and 100 percent of pathogens from domestic sewage to make 764,000 gallons per day of reused water available to Redwood City that’s suitable for irrigation or toilet flushing. Not for drinking. Yet.

The city has an extensive recycled water distribution system already in place, and plans are moving ahead that would allow SVCW to put up to 12 million gallons of highly treated water a day directly into the domestic water system, half for Redwood City and half for San Mateo, either by piping it into Hetch Hetchy’s Crystal Springs Reservoir for mixing or directly into the water supply.

Alicia Aguirre has a foot in both the water retail and water treatment camps as the Redwood City Council’s representative to Silicon Valley Clean Water, where she is chair. She points out that the wastewater treatment plant’s long-term improvement plan, which goes by the acronym RESCU, will pump $550 million into a number of projects leading toward increased reuse.

Aguirre says it will help keep down the cost of water in the long run. “The bottom line is this is going to be a benefit for our society,” she said, “and, by the way, it’s not going to be as expensive” as desalination or other approaches.

Several things have to happen first. Water retailers — cities and water districts — have to foot the bill for the necessary advanced water treatment facilities. And the sewage treatment agency either has to be given legal authority to become a water retailer or has to partner with existing water retailers. In any case, the fate of the wastewater agency is to become simply a water agency.

What Goes Around

Teresa Herrera is the manager of Silicon Valley Clean Water. She thinks these steps “absolutely” will happen. “It’s been such a long time coming,” she said. “I’ve been in the industry 34 years. When I got out of college for my master’s we were talking about potable reuse then, in 1988. It’s such a long time in coming. The concept of ‘water is water’ is finally coming around.”

SFPUC water manager Ritchie says San Francisco also is looking at direct reuse of potable water by injecting groundwater wells with it. “You have to plan for it all,” he said, “reuse, desalination, the suite of diversified water supplies. I think they are very much going to be a part of our future.”

As for the ‘ick factor,’ Ritchie has been dealing with that for years. “Yes, the ‘ick factor’ gets in the way, but the time comes around when people are going to want to make sure there is water of some kind there. “We’re only dealing with the same set of molecules we’ve ever been dealing with before,” he said. “They’ve all been through lots of things over the millennia.”

Apropos of millennia, millennials are far from happy about the climate previous generations have left them with, nor are they pleased with what the current generation has proposed to address the crisis.

The “youth4” movement pre-empted last month’s COP26 international governmental climate confab with its own global youth-only summit in Milan, out of which came a “Youth Driving Ambition” manifesto and calls to action.

Youth want be involved at every level in the decisions affecting climate because “global citizens under 30 are inheriting a hotter, more unpredictable climate that has enormous implications for their future.”

They want to halt the rate of climate change by 2030; the manifesto is called “ambition” after all.

The wastewater treatment plant CEO would like to see it, too. “It’s climate change for sure,” Herrera said, “but also there was also a generation that, to put it bluntly, really got off the hook of not having to invest too much money in infrastructure.”

So far, planning for an uncertain water supply has taken a traditional approach: see if it’s possible to buy a way out of crisis.

“I don’t think there’s a way out of it,” she said, “It’s just not sustainable. I don’t think people are going to have a choice.”