“How would you like your cell-based protein cooked?” That’ll be the question for restaurant servers if Redwood City’s Impossible Foods delivers on its promise to eliminate meat-based agriculture by 2035.

Should that ambitious mission succeed, the Peninsula once again will be in the vanguard of a meat revolution. At the turn of the 19th century, San Francisco’s fresh meat slaughterhouses waged a “butcher war” with South San Francisco over refrigeration. Refrigeration won, but both sides profited in the long run.

It was a minor development in meat, however, compared with the change Impossible forecasts.

Meat is a vast array of things political, sexual, economic, cultural, ecological, technological and even romantical—name it and meat probably is in the picture somewhere.

Academics have established that meat has a gender component, that men and women react differently to meat, that meat conveys a masculine component if it’s red and a feminine one if it’s, say, chicken.

The key signal comes from blood. And blood, or, more accurately, its substitute, is at the core of Impossible Foods’ business.

How It Began

Its founding story is that highly regarded Stanford Medical School biochemist and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator Pat Brown conceived an idea to save the planet: Eliminate meat agriculture. The something to replace it, he reasoned, would be plant-based and should smell, cook and taste like meat. That eliminated then-available plant-based meat substitutes because they were sold pre-cooked with artificial flavors and aromas built in.

The solution Brown favored pointed to heme, a family of proteins in meat that give it the look when raw, the smell when cooking and the taste of eating meat. Impossible claims to be “the first” to identify heme as key to meat for looks, cooking and taste. Its flavor is a distinct taste sometimes identified as savoriness, or umami.

All living things, plant or animal, contain heme protein; however, animal and plant hemes differ. Hemoglobin, the abundant iron-rich, oxygen-carrying constituent of blood, is abundant in animals. When in muscle tissue it is a cousin, myoglobin.

Among plants, soybeans are among the best heme producers. They produce a small amount of heme, legume hemoglobin, or leghemoglobin for short, in nodules on roots. Compared to the heme Americans consume in 55 billion pounds of beef, veal, pork and lamb a year, soybean heme’s production is miniscule.

Producing its additive soybean leghemoglobin requires industrializing the process. Growing fields of soybeans to harvest tiny root nodules has obvious limitations. The company devised a system to boost soybean heme production through genetic modification of yeast. The method extracted soybean’s leghemoglobin-making gene and inserted it into yeast DNA. The yeast does its work, making leghemoglobin, in a fermentation tank, the same technology beer brewers use.

The process is at the core of company claims about its economic, environmental and societal advantages over cattle ranching and meat slaughter. It is also scalable and therefore critical to Brown’s 15-year timetable for eliminating meat agriculture.

As he put it during a November radio interview with the Palo Alto Humane Society, “the way we make meat uses way less land, way less water, one one-hundred twenty-fifth the land area, one eighth the water, less than a tenth of the fertilizer and agricultural chemicals, less labor growing the crops because we use labor more efficiently, no labor managing the animals and less labor in manufacturing.

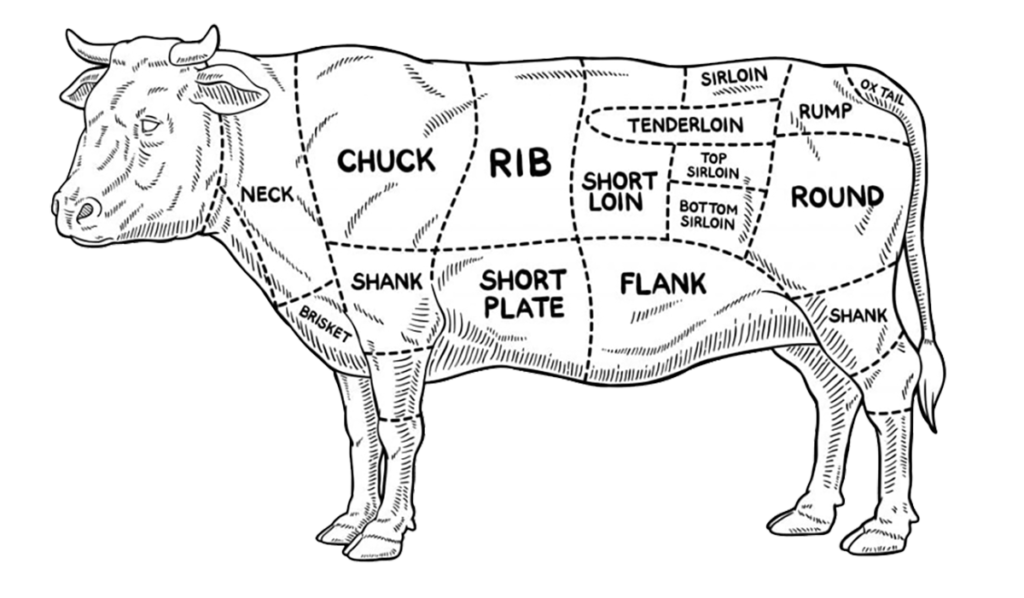

“We designed the whole process, as opposed to having this ungainly creature come in the door and be hacked to pieces by a bunch of exploited workers with large knives.”

Carnivores and Vegans

This last characterization repeats the conundrum of the “meat paradox:” Most humans do not approve of the kill and slaughter of meat animals, but they love to eat the meat. Human teeth and stomachs are designed for it. To a degree that thus far has not been quantified, the success of the transition to plant-based meat partly will depend on how attractive it is to consumers not to struggle with the meat paradox. Most people, with intent, just don’t think about it. Of those who do, some reject meat entirely, as do vegetarians and vegans, or avoid it, as do flexitarians; however, eschewing meat is a minority movement. According to Gallup, only 5 percent of Americans are vegan or vegetarian, and it’s mostly a non-white, liberal, 18-to-34-year-old phenomenon.

Meat eaters may find Brown’s other arguments persuasive.

—

This story appeared in the March edition of Climate Magazine.

—

“Replacing animal agriculture over the next 15 years would unlock negative emissions sufficient to offset all other greenhouse gas emissions for 30 years … Eliminating animal agriculture does what you can never do with fossil fuel emissions,” he said. “It unlocks massive negative emissions. You can reverse animal agriculture emissions, historic emissions, almost completely. At the same time, the same thing will almost completely reverse the collapse of global biodiversity, which is almost entirely due to animal agriculture and overfishing.”

Impossible’s mission is global.

“Our long-term plan is to be everywhere,” according to a company spokesperson, “in every market globally, and have a full array of products for every culture and cuisine. That means scaling to produce over one trillion pounds of plant-based meat, and our goal is to do that by 2035.”

“I am 100 percent confident,” Brown said in that November interview, repeating what he has said many times, “that we’ll replace (animals in the food system) within 15 years.”

Grand declarations such as those bring to mind Elon Musk and Tesla. Musk may have been the only one who believed he could eliminate gas-fueled cars, but through the influence of economics and official policy, that pledge is on the way to being fulfilled. Success moving humanity to Mars—Musk’s signature ambition—may be more difficult, but in that goal he already has government science and funding on his side.

The Disruption Model

Musk may not be the model, but Impossible’s playbook follows his, and that of the archetypical Silicon Valley tech company’s: disrupt the status quo, attract capital and scale up.

“End the cruelty of meat slaughter” and “save the planet” are excellent clarion calls, and investors have responded, reportedly with $1.4 billion in funding, according to filings by Maraxi, Inc., another Pat Brown company under the Impossible umbrella. Market watchers have touted the value of an Impossible Foods initial public offering of stock, should it ever decide to become publicly owned, at $10 billion.

Reuters has identified some funders: kicking in a reported $300 million were celebrity investors Serena Williams, Katy Perry, the rapper Jay-Z, The Daily Show host Trevor Noah, will.i.am, Ruby Rose, Jaden Smith and others.

Public filings also disclose the participation of several billionaire investors and investment funds, among them Vinod Khosla’s Khosla Ventures. Khosla was founder of Sun Microsystems and is partner at venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caulfield and Byers. He’s noted locally for litigation with San Mateo County and the California Coastal Commission over public access to Martins Beach, a Khosla property on the coast side.

Others are Temasek, a $380 billion investment portfolio based in Singapore, and multi-nationals, Mirae, UBS Capital, Viking Global Investors and Coatue, an actor in crypto analytics.

Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates has gone farther, devoting time and talent to the cause, in addition to money —$50 million, according to published reports.

Last May he told the Economic Forum of Washington that, “of all the categories, the one that has done better than I would have expected five years ago is this work to make what’s called artificial meat.

“So you have people like Impossible or Beyond Meat, both of which I invested in … It’s slightly better for you in terms of less cholesterol. Of course, there’s a dramatic reduction in methane emissions, animal cruelty, manure management and the pressure that meat consumption puts on land use.”

Gates faulted “cows and other grass-eating species” for emitting 6 percent of global methane emissions. “So we need to change, just cows alone.”

What to Call It

He enters a semantic thicket, however, to say “what’s called artificial meat,” because industry tends to avoid “artificial.”

Impossible Foods uses “plant-based products” or “plant-based meat” generically, but leans on its trademarked word, “Impossible,” as in Impossible Burger, Impossible Sausage, Impossible Chicken Nuggets and Impossible Pork.

Other terms: cultured meat, meat protein, plant protein alternative, meat analogue, meat substitute or alternative meat product. Variations are numerous, but because of potential legal problems, including lawsuits, “veggie” can be off limits. The basic proteins in the majority of plant-based alternative products are, like soybeans, from legumes, not vegetables.

What to call the products seems still in flux, spurring companies to get creative. Gardein, branded as “the plant-based protein” company, avoided the common stratagem of tacking an adjective—or two or three—onto “meat” and coined product nouns. Though they convey the idea when read, it may not be possible to pronounce them without losing meaning. It may not even be possible to say some of them using standard English sounds: “Be’f,” “Saus’ge,” “Chick’n,” and ‘Ste’k.”

‘What is meat?’ may be a problem for a nascent plant-based industry not least because the federal authority on the subject, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, defines meat as “the flesh of animals (including fishes and birds) used as food.”

That First Beef War

For generations, since Gustavus Swift opened an abattoir in South San Francisco and helped build a town to house the people to work in it, “meat” meant more than “tissue,” it was the muscle meat of slaughtered farm animals bred for the purpose by a meat industry, which in 2020, the last complete year of the USDA meat census, processed nearly 10 billion cattle, hogs, sheep, lambs, chickens and turkeys.

The beef slaughter has been losing meat market share for several decades. The 32.8 million head of cattle processed in 2020 is down from a high of 45 million head in 1975; however, beef remains meat’s mainstay because compared to other animals one cow yields a very large quantity of high-quality protein and commands a high price here and overseas.

Impossible Foods and Bill Gates emphasize the negative, that to create protein cows take up lots of space, generate troublesome waste and contribute to global warming.

Brown calls beef production “by far the most destructive technology in human history.”

A company statement claims “that the yield of protein in the U.S. soybean crop is five times greater than all the protein in all the meat consumed in the U.S. By using our ingredients, including soy, far more efficiently in our supply chain than in the livestock supply chain, we need less of them, thereby decreasing demand for ingredients like soy every time an Impossible product replaces animal meat.”

Soybeans already represent the second-largest crop in the U.S. next to corn, and, while land devoted to crops today is about the same as it was in 1917, the portion devoted to soybeans is growing fast, jumping 26 percent over 2012 to 329 million acres in 2017. Land devoted to pasture fluctuates year-to-year. As of 2012, pasture and range acreage, at 655 million acres, was up over the annual average.

The numbers indicate that soybeans are taking over lands already in crops, not pasture land, but even should it come to the point where animal and soybean farming have to compete for land, cattle producers don’t believe range and pasture land will convert. Rangeland usually is hilly, rocky, dry and untillable. Cattle are among the few animals able to thrive on it.

The Rancher Reaction

The industry Impossible hopes to disrupt, the one whose longevity seems about to be curtailed, is not reacting very strongly to the threat.

With the help of sympathetic members of Congress, they have drafted legislation, the Real MEAT (Marketing Edible Alternatives Truthfully) Act, to establish a federal definition of meat.

It also has filed a request with the Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration to “enforce existing labeling laws for plant-based protein products,” existing laws developed over generations to benefit the meat industry as it has been known.

As it hasn’t been voted on, the Real MEAT ACT has done little, other than provide a platform for press releases in which the cattlemen can lambaste “fake meat,” “misbranded imitation meat” and “lab-grown” meat while poking the FDA.

Danni Beer, a South Dakota cattle rancher and a member of the United States Cattlemen’s Association, says labeling, not technology, is the crux of the issue, and in her opinion plant-based food companies are stalling. “They publish press releases saying ‘We’re going to come forward,’ but it seems every time they need a round of funding they come out with a release.”

She does not feel a sense of existential dread. “Sometimes when I listen to their propaganda it scares me that people will believe that information,” she said. “When I look at how much of the market share they are actually selling compared to meat, it doesn’t scare me at all. I really have a lot of confidence in our product, because it’s good.”

Elimination of meat agriculture, she said, “sounds like something that I can’t imagine in my lifetime or my children’s lifetime either. You can’t break it down to be that simple.”

Cattle rancher Beer says she’s very interested in plant-based meat technology—she calls it “cell-based protein”—and is “impressed with how much they believe in it.”

Cattlemen are frustrated that companies work in secret while agricultural meat production is heavily regulated, in the open and government-inspected.

A Lucrative Market

Secrecy may be as simple as the fact that no company yet in the plant-based, cell-based alternative meat business has unveiled the metaphorical rocket to Mars that signals the end of the development phase, the “killer app” that slays all competitors and sets the course for all to follow.

It’s not for lack of effort. At stake is business worth at minimum billions, possibly trillions, of dollars.

Even traditional meat mega-companies are muscling in. Conagra Brands is on the market with its subsidiary Gardein. Cargill, Inc. the world’s largest privately held company, is marketing PlantEver plant-based “beef patties” and chicken nuggets in China and has invested in “other alternative protein products” in Asia and the U.S.

To give meat its due before its disappearance, scientific literature, primarily works cited in the Woodford Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, makes these points.

Animal tissue becomes meat when it dies. What makes it palatable is “postmortem metabolism,” a process that after cell death develops those constituents which humans covet in meat. It differs from plant protein in that it is able to hold a large amount of water, giving it juiciness. Meat has almost no carbohydrates.

In addition to containing about 20 percent high-quality protein, beef is a significant source of many nutrients. These nutrients can be derived from nonanimal sources, but meat concentrates them and is unique in delivering them in a single food. Meat animals screen toxins from the plants they eat. Meat protein is superior at making muscles grow.

Meat protein differs from plant protein, in the words of Dr. Bruce German, distinguished professor and chemist in UC Davis’ Food Science and Technology Department, in that “plants are not really very nourishing, they didn’t evolve to nourish us. In fact, they evolved to avoid nourishing us.”

Dr. German is researching a third way of delivering food protein, a method using the protein-producing power of human breast milk — some argue the perfect protein — harnessing microbes, as Impossible Foods does, to do the work in fermentation tanks.

Like Brown, he believes “the current agriculture system is just not sustainable. At least a third of the destruction of the planet’s land, air and water is attributable to agricultural activities … We are going to have nine, 10 billion people on this planet. How are we going to nourish them?

“The meat idea is not a bad one, but the question is, could we do it better?”

The technology is established. The ‘what’ is not. “People think it will be one thing,” he said. “It won’t. Everybody has a different response to food and somewhat different aspirations for health. We’re going to have to include diversity into this whole thing.”

The future will be “precision nutrition, delivering diets to people that help their particular health issues and their desires. In so doing, wouldn’t you want to know what they like in terms of flavor, texture?”

There will be cattle, he said, but not many. “Maybe on your birthday every year you’ll get a steak. The rest of the time you’ll say, ‘I really don’t like steak that much. Can I get X?'”

Correction: This original story misstated the affiliation of Danni Beer. She is a member of the United States Cattlemen’s Association, not the National Cattlmen’s Beef Association. The story has been updated to correct this.