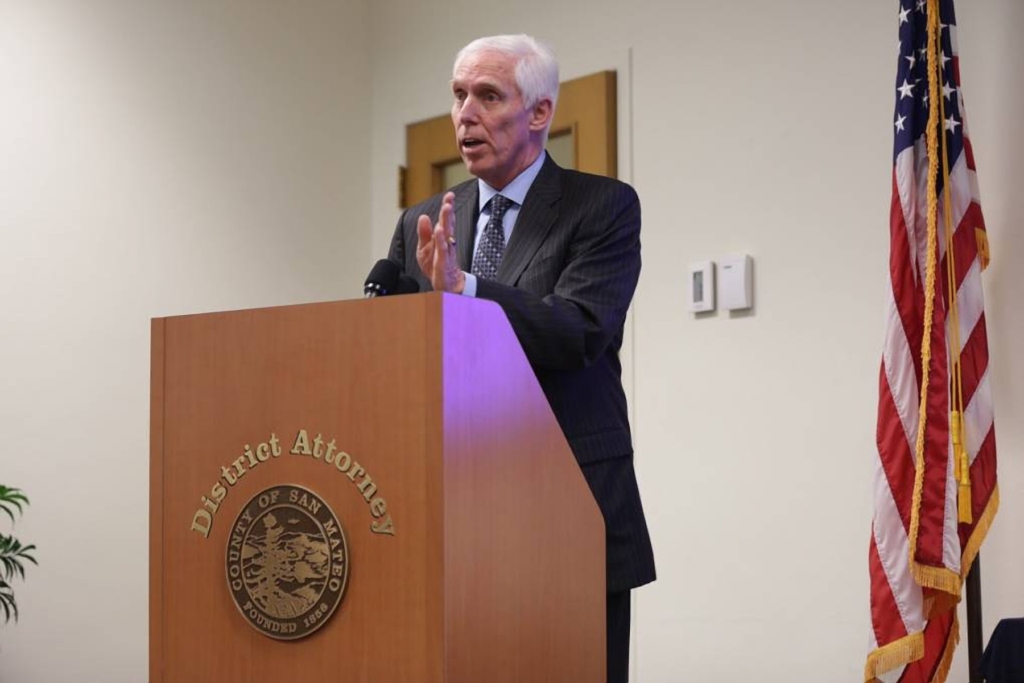

San Mateo County District Attorney Steve Wagstaffe is ever mindful that he walks in the footsteps of history. Son of local civil attorney Gerard “Gerry” Wagstaffe, Steve followed his father into the legal profession after graduation from the University of Notre Dame and Hastings Law School, then took his first and last job as a lawyer in the San Mateo County District Attorney’s office in 1977.

In 2011, 34 years and 34 murder prosecutions later, Steve Wagstaffe was sworn in as the county’s top prosecutor at the old courthouse in Redwood City—the same spot where his father’s law partner and local legend Joe Bullock retired as San Mateo County District Attorney, 100 years earlier.

When Wagstaffe begins his fourth (and what he says will be his final) unopposed term in January 2023, he will mark 70 years of leadership by only three top prosecutors. It’s a record unparalleled in the state. There have been only three district attorneys in San Mateo County since 1953: Keith Sorenson, who served seven terms; followed by his chief deputy, James Fox in 1983, who also served seven terms; who was in turn succeeded by his chief deputy, Steve Wagstaffe, in 2011.

This record of leadership could only be sustained, in Wagstaffe’s view, by a reverence for justice. “We try to treat everybody fairly,” he says. “Prince or pauper, cop or criminal, we treat them all the same. It’s a good standard for this community. That’s why we’ve only had two elections in the past 69 years.

—

This story appeared in the March edition of Climate Magazine.

—

“Keith and Jim were the best prosecutors I met out of thousands,” Wagstaffe continues. “They set a standard for high integrity, high ethics. They wanted a county where people were accountable for their conduct. I am just trying to follow what they taught me.”

Viewed from the wrong side of the law, San Mateo County has a notable distinction, according to Wagstaffe. “Number one,” he says, “criminals know that in this county they’ll be held accountable. In San Francisco or Alameda, they’ve got so much murder, rape, and robbery, that they honestly don’t have the resources to pay attention to the quality-of-life crimes. Here we do.”

One thing most law enforcement professionals seem to agree on is that the criminal justice system follows public sentiment, much like a pendulum.

Crime, especially homicides and violent crime, has soared throughout most of the country in the past two years. George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis policeman sparked months of anti-police protests and riots in 2020. Occupy zones sprang up in Portland, Ore., Seattle, Wash.; and elsewhere. The subsequent calls to defund police and DAs declining to prosecute led to elevated public concerns about a state of lawlessness not seen since the early 1980s.

An Eye in a Storm

San Mateo County may be the outlier. It is California’s 15th largest by population and second wealthiest, yet remains the second safest per capita, despite troubling incidents of crime and disorder that have rocked other localities around the Bay Area and urban areas nationwide. Anti-police brutality protests which took place in San Mateo County were peaceful. And, the recent, organized smash-and-grab gangs haven’t looted high-end stores and malls, unlike in neighboring counties.

“Criminals may not be the smartest bears, but they know they’ll be held accountable in San Mateo County. We set a high standard,” Wagstaffe says, by way of explanation. Sheriff Carlos Bolanos agrees. “We’ve actually had criminals tell us this: ‘We don’t want to come to San Mateo County to commit crimes, because law enforcement will catch us, and the DA’s office will prosecute us.’”

Though police and prosecutorial overreach may make the headlines, less noticed is the long-term trend in law enforcement in favor of rehabilitation and diversion programs for non-violent crimes over incarceration. “There will be accountability for conduct,” Wagstaffe says. “The other side is compassion. You have to have compassion. Only a very small percentage of the criminals we deal with are evil. Most we can help, so no more people will become their victims.”

Wagstaffe served eight years on the board of the California District Attorneys Association and as president from 2016 to 2017. In that capacity, he has worked with other top prosecutors, both state and federal, in supporting a number of criminal justice reforms.

But not all. Wagstaffe was a vocal opponent of Proposition 47, a ballot initiative which passed in 2014 that, among other things, reduced certain felonies to misdemeanors. Prop. 47 passed despite warnings by every top law enforcement official in California that it would lead to higher crime, a warning that many say has been proven true. (Others contend that a cause-and-effect relationship can’t be documented.)

Alternatives to Jail

Creating alternatives to incarceration may seem incongruous for a prosecutor, but it is consonant with Wagstaffe’s upbringing and Catholic education, as well as his childhood impressions of how the law is practiced. “Watching my father, what he was doing for people … I could see how the people really respected him, and my original plan was to go into practice with my father,” Wagstaffe recalls.

“When I was 14, I used to ride my bike to Redwood City to watch trials, and I remember a special murder trial. The man was convicted of killing his girlfriend and burying her body up on Skyline. That to me was fascinating.” The prosecutor in that case was a fellow named Bob Bishop who later became the Chief Deputy DA—and Wagstaffe’s first boss.

Wagstaffe prosecuted many types of crime through his career as a trial lawyer, but homicides continued to fascinate him, and became his specialty. Winning election to the top job took Wagstaffe out of the courtroom and he devotes his time to administration of a multi-faceted, high-profile department. Since his election in 2010, he has only prosecuted one murder case. That was the retrial of Mohammed Haroon Ali, convicted in the 1999 murder of Tracey Biletnikoff, the 20-year-old daughter of Oakland Raiders Hall of Fame wide receiver Fred Biletnikoff.

“I tried the original case and convicted the guy,” Wagstaffe says. Though the conviction was sustained through nine years of appeals, eventually a federal panel ordered a retrial. Wagstaffe continues, “I always get to be very close to the victim’s family, and what mattered to me was being there for the Biletnikoff family.” Today, the murderer is serving 55 years to life in prison.

Wagstaffe keeps a picture of Tracey Biletnikoff in his office, as he does for all the victims of murder cases he prosecuted. “Everything for me is victim-focused. I’ve gotten to get to know their families and worked to give those people a feeling of justice.”

Asked which he values most—mercy or justice—Wagstaffe doesn’t hesitate: “There is a place for mercy. Justice is in every case.”

One of the most consequential prosecutions that has come out of his office has been a recent one, a massive case of fraud. It began with a jailhouse telephone conversation, overheard by one of his investigators, which unraveled a conspiracy to swindle state government out of $20 billion in pandemic-related unemployment claims. Wagstaffe quickly notified the state’s Economic Development Department, other DAs, jailers and state and federal prison authorities, launching a major prosecutorial effort led by former U.S. Attorney McGregor Scott.

“Steve’s office was really on the front edge of this thing, way back 15 months ago,” Scott says. “He had one of the first real prosecutions around the EDD fraud.” Prosecutions of 21 San Mateo County residents (including 11 inmates) and dozens of others across the state, the nation and the world are continuing, although according to Scott “only pennies on the dollar” will be recovered.

As DA, Wagstaffe oversees a budget of $47 million and an office involved in approximately 20,000 cases a year, everything from traffic infractions to felonies. His staff of 129 includes attorneys, investigators, program administrators, support staff and victim advocates. Local prosecutors may also bring actions under consumer and environmental laws, and the DA’s Victim Center provides crisis intervention and emergency assistance, including helping victims apply for compensation for crime-related expenses through the state’s Victim Compensation & Government Claims Board.

A Road Not Taken

Though he came from a family of lawyers (two brothers also followed their father into law), there was a time when Steve Wagstaffe might have chosen a different career path. After graduating from a six-day-a-week college prep school run by Benedictine refugees fleeing Soviet expansion into Hungary, Wagstaffe headed off to Notre Dame. Inspired by President John F. Kennedy’s famous injunction, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country,” and with an extra day on his hands; he began volunteering at a residential hospital for kids with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

His volunteer work evolved into a full-time job, and Wagstaffe seriously considered remaining a special education teacher. “I just loved it, loved the kids,” he says. That job is also where he met his future wife, Susan. Married 48 years, the Wagstaffes have two sons (one a prosecutor in Alameda County and the other a high school dean) and four granddaughters.

Wagstaffe still volunteers to help kids and the community as a whole, serving on boards for the YMCA of Silicon Valley, the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Activities League and the Service League of San Mateo County. In 2014, he served as president of the 100 Club, which provides financial assistance to families of fallen police officers. He is also involved with several criminal justice task forces.