By Kathleen Pender

For millions who worked from home the last two years, the dress code was anything goes. On Zoom meetings, they might don a dress shirt or blouse, maybe even earrings and makeup. Otherwise, sweats all day were okay, even PJs. Now, workers heading back to the office, at least part-time, face the age-old conundrum: what to wear. The same goes for social events, which are coming back. Can they resurrect those dresses and suits from the back of the closet, or is it time to spring for something new?

No one has more riding on these answers than apparel makers and retailers. The fashion industry underwent an unparalleled makeover during the pandemic. While esteemed retailers such as Brooks Brothers and Neiman Marcus filed for bankruptcy, “athleisure” brands like Lululemon and Nike were off to the races. Shoppers turned to the internet for retail therapy, and online apparel sales swelled.

After plunging in 2020, U.S. garment sales picked up in 2021 and ended the year ahead of 2019. The recovery, however, was led by a small group of leading brands. Many companies are still struggling to survive. “The few brands that outperformed either played into the needs of the moment — comfort, outdoor activities and online shopping — or appealed to wealthier cohorts who were able to better weather the impacts of the crisis,” consulting firm McKinsey said in its 2022 State of Fashion report.

Dayna Marr, who owns the Pickled women’s boutique in downtown Redwood City, survived the early days of the pandemic by ramping up online sales. Her stylists FaceTimed with customers and would drop off packages at their door. “It was all sweats and comfort clothing,” Marr said.

Her lowest point, however, came this January, when the Omicron strain was at its peak. “That was the most painful month I’ve had in my 30 or 40 years of retail,” she said. “People had Covid, were afraid of getting Covid or quarantining because they’d been exposed.” If they came in to return Christmas gifts, they made it clear they weren’t there to browse.

Night and Day

Things started picking up just before Valentine’s Day. Then on Feb. 16, San Mateo County lifted its indoor mask mandate, and it was like someone flipped a switch. “I have people coming in daily saying they need a closet update because they haven’t really shopped in a couple years. People are getting together socially, wanting to go back to work.”

They’re looking for denim, high-waisted pants, dresses and sneakers to wear with them, shorter crop tops, resort wear and jewelry. “The more color, the better,” Marr said. “When you do comfort clothes for so long, people want to dress up more, feel a little more put together and back to normal,” she said. “People are not afraid to spend money.”

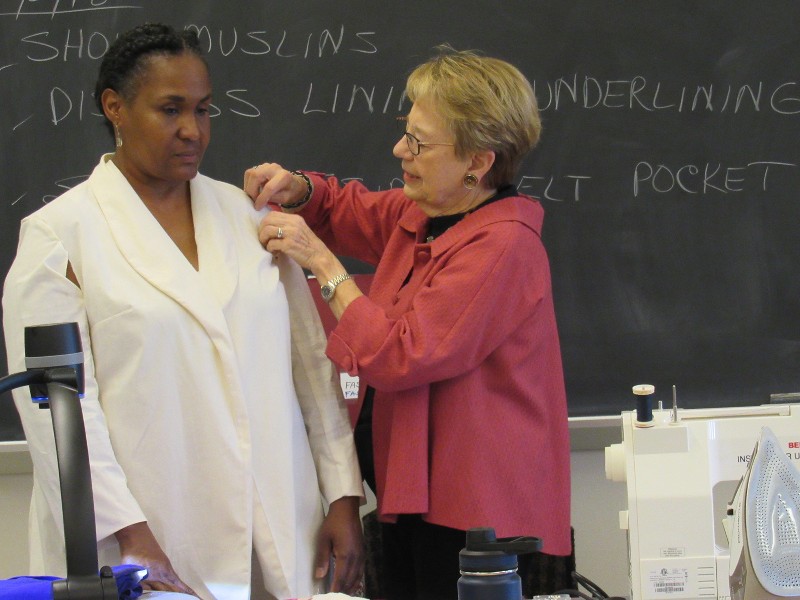

Indeed. Americans as a whole have never been richer, thanks to government stimulus, rising home and stock values and not having spent much for two years. Many people are eager to update their wardrobes with fresh styles and bright colors. “After about a year and a half of the pandemic, people were making appointments with their personal shoppers,” said Ronda Chaney, coordinator of the fashion design and merchandising department at Cañada College.

—

This story appeared in the May edition of Climate Magazine.

—

But they’re not always finding what they want. Apparel is a complex global industry, facing supply-chain disruptions, rising shipping costs and staff shortages. Susan Marquess of Mountain View needed travel pants for some upcoming trips. Nordstrom’s website said they were in stock at the Palo Alto store, but when she got there, no pants. The salesperson’s response: Look online. “It’s frustrating, she said.

Three Trends

Fashion experts say three trends that accelerated during the pandemic – online shopping, more-casual dressing and sustainability – are likely to continue. And shoppers seem more willing than ever to pay up for high-end goods.

Last spring and summer, Chinese consumers released from their strict lockdown went on a spending spree, nicknamed “revenge buying.” Their penchant for luxury goods helped fuel a surge in sales for the French firms LVMH (owner of Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Fendi and other high-end brands) and Kering, whose fashion houses include Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent.

Their 2021 revenues were up a striking 44% and 35%, respectively over 2020, but a significant part of those gains stemmed from price increases, said Andrew Tam, an analyst in London with CFRA, an investment-research firm. “Their kind of customers have been less impacted by the pandemic.”

A growing secondary market for things like Swiss watches, Birkin bags and other designer goods is also fueling sales. “We’ve heard that in places like Russia, where the ruble has plummeted, they have been buying luxury goods as a way of getting something tangible,” Tam said. (Many stores have since closed their Russian locations.)

A stroll around Stanford Shopping Center in Palo Alto on a warm Sunday afternoon in March highlights the uneven nature of the retail recovery.

Brooks Brothers and Burberry were nearly empty. But there were eight people waiting to get into the Louis Vuitton store, which serves only two customers per salesperson at a time, an employee said. Lululemon had seven people in line for the cash register, proving one can never own too many yoga pants.

A Wave of Bankruptcies

J.Crew and its younger sister company Madewell were busy, even though their parent company was the first major retailer to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy after the pandemic. It was followed by companies such as J.C. Penney, Neiman Marcus, Lord & Taylor, Stein Mart, Brooks Brothers, Tailored Brands (parent of Jos. A. Bank and Men’s Wearhouse), Francesca’s, Lucky Brand, True Religion and Ascena Retail (owner of Ann Taylor and Lane Bryant).

All of these companies are still operating, in some fashion. Most were either sold or exited bankruptcy after having been reorganized. Lord & Taylor and Stein Mart returned only online.

To survive, companies have had to adapt. Zegna’s, which sells expensive menswear from Italy, revamped its product line in favor of casual wear, with splashes of bright green, yellow and royal blue, said Francesco Carugati, manager of the Stanford location. Before the pandemic, about 70% of the store’s apparel was formal wear; now it’s 30% to 35%. Sneakers have vaulted from 35% of its shoe line to 85%.

By mid-2021, the store’s sales were back to pre-pandemic levels, even though foot traffic is still down by double-digits. The key was developing closer relationships with customers – even those who had moved to Montana – by showing them merchandise on FaceTime, shipping it to their homes and letting them return whatever they didn’t like. It’s also spending more on tickets to sporting events and restaurant dinners for clients.

Even before the pandemic, if people bought a suit from the store for work, it was because they were traveling to the East Coast or Europe. “Our business is related to the social life of our clients,” Carugati said. And that’s coming back strong. “Weddings are a big part of our business, and we have huge demand for June 2022,” Carugati said.

Investing in a Dress

More than ever, people are looking at luxury goods as an investment, said Francesca Sterlacci, CEO of University of Fashion, an online library of fashion design videos. She was surprised to see items from Supreme – which sells limited-edition streetwear to a cult-like fan base – at a Sotheby’s auction. A plain white t-shirt with a Supreme logo was listed on Sotheby’s website in March for $2,200.

Retail consultant Ken Hewes knows people who calculate the resale value of an item when they buy it. “It allows them to buy more luxury goods,” said Hewes, president of Mod Advisors.

Many consumers are selling, buying or renting designer duds – and more mainstream brands – on websites such as StockX, Rent the Runway, Poshmark (based in Redwood City), thredUp and The Real Real (both based in San Francisco) and of course eBay (based in San Jose). Poshmark’s hot trends for spring include vacation wear, bridesmaids and prom dresses and “dopamine dressing,” the post-pandemic term for bold, vibrant colors.

Online resale appeals to budget-minded fashionistas and the growing number of people who want to reduce their environmental footprint. When Sterlacci lived in Portola Valley, she loved going to second-hand shops in Palo Alto, where “wealthy Silicon Valley ladies” put clothes on consignment, sometimes shoes they hadn’t even worn. “Now you see these same rich ladies shopping there, as they become more sustainable-minded,” she said.

Thrift-Shopping

At Cañada College, which offers 37 classes in fashion merchandising and design, “People are really caring about sustainability,” said Ronda Chaney, the fashion department’s coordinator. “They are talking in our classes about where they purchase clothes and how you determine if they are sustainable. They are thrift shopping more.”

College students Penelope Alioshin and Abigail Walker, who grew up in Palo Alto, haven’t bought new clothes since junior or senior year of high school. They do buy new shoes, because the ones donated to Goodwill are usually worn out.

“We thrift almost everything,” Alioshin said. In San Luis Obispo, where she attends Cal Poly, “they have Goodwill bins where they sell clothes by weight. You have to have time to sort through them, but it’s kind of a fun activity.”

Walker, dressed in a pair of jeans she’s had since seventh grade, said she tries to buy pieces that will last longer. She attends the University of Texas at Austin, where she is doing research on ethical garment production and consumption. “Companies have found that they can market sustainability,” Walker said.

But garments marketed as organic, recycled, vegan or carbon-positive usually cost more, and it’s hard to know they are, in fact, environmentally friendly. Many retailers are jumping on the sustainability bandwagon by taking back old clothes that they promise to recycle, resell or reuse. In exchange, they usually offer customers a discount toward the purchase of new clothes, which could end up in a landfill. Some consider this practice “greenwashing,” or conveying a misleading impression of one’s environmental practices, Sterlacci said.

Some new designers are taking sustainability one step further by using 3-D design software to create prototypes. Instead of getting samples shipped, buyers can see the design on a digital avatar, Sterlacci said, and ask the designer to make changes on the virtual model.

Disposable Clothes

While many younger buyers are thrifting, others are gobbling up throwaway fashions from companies such as Shein, the world’s fastest growing e-commerce company. The privately held company sells cheap togs – such as $11 dresses and $13 swimsuits – over the internet and ships them directly to customers from its factories in China.

Alioshin said Shein (pronounced She-In) is popular on her campus. Even her friends who thrift will buy “cute little tops for going out,” she said. “At the end of the quarter you find bins where people who are moving can donate clothes. They are full of Shein – St. Paddy’s Day shirts or something they wore to one party.”

Experts predict that online apparel sales will continue to grow, but not like they did in 2020 when consumers couldn’t or wouldn’t visit brick-and-mortar stores. It turns out clothing is one thing many shoppers still like to see and feel. Ruthie Lax, a senior at Sequoia High School, said she shopped online a lot more during the pandemic, but bought fewer clothes because you can’t try them on first “and it’s a hassle returning things.”

So as people emerge from their pandemic cocoons, how will they dress? For work, the consensus is that they will dress pretty much like they did before the pandemic, but a little more casually. What that means varies by location. In central London, “People are back to wearing suits,” Tam said. “It might be without a tie, but they still wear suits.” However, most will continue to work from home part-time, and that means they will only need two or three suits, not five.

Trending More Casual

In the Bay Area, casual Fridays turned into casual everyday years ago. “Silicon Valley led the way in this respect and inspired change in a lot of other professions. Even in pretty conservative professions such as law, jeans and a sports jacket are fine, said Richard Ford, a Stanford University law professor and author of “Dress Codes,” a book on fashion history. “Casual clothing in Silicon Valley signals two things: Someone is a free spirit and a free thinker.”

As workers return to the Stanford campus, “I haven’t seen a huge change” in their attire,” Ford added. “I do think it will be more casual. That doesn’t mean there will be no dress code. There will still be very specific ways that people dress for specific professions.”

Before the pandemic, the “midtown uniform”– button-down shirt, slacks and a fleece vest, preferably from Patagonia – was the standard outfit for finance bros. “It’s casual but it’s still a specific type of clothing that all of these bankers wear,” Ford said.

In Silicon Valley, “creative types dress differently than coders. VCs dress differently than executives,” he said. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s signature hoodie said he was too focused on his job to worry about clothes, but a hoodie with a sports-team logo “doesn’t read professional.”

For socializing, Ford and Tam said people may want to dress fancier, in more brand-name clothing, than they did pre-pandemic.

During the lockdown, people dressed up to take out the trash. “They’d bring a bottle of wine and stand around with their neighbors in cocktail attire,” Ford said. They were also interested in “shows that revolved around clothing, like “Bridgerton” and “The Queen’s Gambit.” I think people are hungry for that.”

What they’re not hungry for is rising prices. Fashion executives’ biggest concern, according to a McKinsey survey, is that supply-chain disruptions could send prices even higher and choke off demand. China, a major clothing supplier, has reimposed some lockdown restrictions.

CFRA analyst Zachary Warring predicts that value and luxury retailers “will hold up best over the next 12 months as inflation hits lower- and middle-income families hard, pushing them too off-price or discount retailers and impacting high earners to a lesser extent.” McKinsey reached the same conclusion, adding that the “the mid-market will be squeezed.”