By Jim Clifford

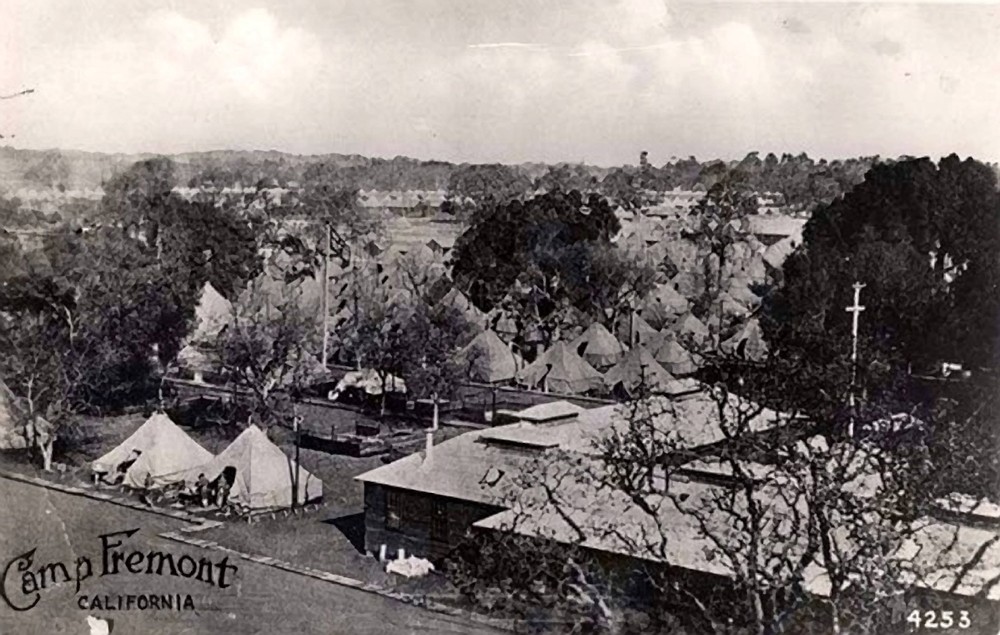

Even with war raging in Ukraine, few people today may remember that American troops once fought in Russia — Siberia, to be exact. About 3,000 soldiers from Camp Fremont, a sprawling World War I training camp that occupied parts of Menlo Park and Palo Alto, served in one of the strangest and least-known chapters of American history.

Most accounts of Camp Fremont note that the vast majority of men who trained there arrived in France too late to fight in a war that bled Europe for three years before America joined the Allies in 1917. Although few Camp Fremont soldiers saw action on the Western Front, at least 353 American troops died in the little-known Russian campaign, according to the website, The Great War 1914-1918 (www.greatwar.co.uk).

One of the best accounts of the American troops’ experience in Russia is, “Golden Gate to Golden Horn: Camp Fremont, California, and the American Expedition to Siberia of 1918.” It was written by Col. William S. Strobridge, a military historian who died in 2006. There’s a copy in the San Mateo County History Museum, on Courthouse Square in downtown Redwood City.

“Siberia had none of the aura of France,” Strobridge wrote. “November’s armistice on the Western Front increased a sense of isolation among men living in box cars along the Trans-Siberian Railroad after marching so recently in San Mateo sunshine.”

There’s little left of Camp Fremont, where more than 42,000 soldiers went through basic training. The camp hospital is now part of the Veterans Health Administration complex on Willow Road. The camp YMCA building was moved to El Camino Real and became the Oasis Beer Garden, now closed. The best-known remnant is the MacArthur Park restaurant, off El Camino near Stanford. Designed by famed architect Julia Morgan, the structure was once a “hostess house” where soldiers could visit relatives.

According to Barbara Wilcox, author of “World War I Army Training by San Francisco Bay: The Story of Camp Fremont,” traces of the camp’s training trenches can be found today. “They practiced trench warfare on a maneuver ground, complete with dugouts and underground galleries on the site of today’s Stanford Linear Accelerator Center National Laboratory south of Sand Hill Road,” she wrote. Wilcox added that trenches and dugouts “emerge after heavy rains,” and ammunition still turns up. An unexploded artillery shell was unearthed in 2010 by a crew digging a swimming pool near the Palo Alto Hills Golf and Country Club.

Why were men sent to fight in a virtual wilderness? Historians have debated that question ever since America’s soldiers returned from Russia in 1920. The usual answers have included protecting American property, keeping the railroads working and helping trapped Czech troops who wanted to continue fighting the Germans after Russia pulled out of the war. Other nations, including England and Japan, also sent troops to Russia. Communists regarded it as an “invasion” designed to crush the Russian Revolution.

According to the U.S. Militaria Forum (a website devoted to all things military), Gen. William Graves, who commanded the American forces, tried to maintain “strict neutrality” when it came to clashes between the White and Red armies. (During the civil war that followed the revolution, the Red Army was communist and the White Army was anti-communist.)

The general’s policy was probably wise. A commentator on the website notes that only around 8,000 U.S. troops were in Siberia at any time, so the Americans would have had a hard time “fighting in anything larger than a minor skirmish.” The author adds that the White forces’ personal conduct was little better than that of the Red Army, and “in some cases (was) much more violent and cruel.”

Graves, who was the commanding officer at Camp Fremont when he was named to head the force in Russia, wrote a book entitled, “America’s Siberian Adventure,” published in 1931. He reported that most Russians, except “the autocratic class,” appreciated that his soldiers avoided taking sides. However, he said offensive behavior by troops of other nations placed the mass of Russians “solidly behind the Soviets.”

(Note: While researching this article, I realized I had a brush with history. My family owned an American Remington rifle that was made in 1917 and was supposed to go to the Czarist forces but was never shipped to Russia. The gun, stamped with the Czar’s crest, belongs to a relative who test-fired it a year or so ago and reported it “in fine condition.”)