It all started when a gust of wind blew Kathy Kopf’s hat into Lake Tahoe.

Not only did Kopf lose her favorite chapeau, made for her by a friend. She also realized she had inadvertently contributed to the scatter of debris accumulating at the bottom of one of California’s best-loved destinations.

The sting of losing to the breeze gradually wore off. But Kopf still found herself bugged by the deeper issue. How much junk was down there, up to 1,645 feet below Tahoe’s surface? How was it affecting the lake’s ecosystem? And what was anybody doing about it?

Tons of Trash

Like many fellow residents of the Peninsula, Kopf and her husband, Jamie, had been vacationing at Tahoe for decades. They met there at a family July 4 celebration 48 years ago, just after Kathy graduated from Woodside High School. Four-and-a-half years later, after college and Jamie’s army service, they were married there. Today, they own a home there. And they have both become heartsick watching a splendid resource gradually devolve into one big trash heap.

“It’s terrible,” Jamie says. “People come up for the day and leave all this junk on the beach, and it all rolls off into the lake.”

Eventually, their annoyance spurred them to action. In 2020, even as Covid shut down most of the world, they recruited their 31-year-old daughter Lindsay and formed a foundation to clean up the lake bottom. The nonprofit organization, called the Restoring the Lake Depths Foundation, aims to pick up all the debris on Tahoe’s lakebed — for a start. The long-term goal is to do the same with every navigable lake in California and Nevada.

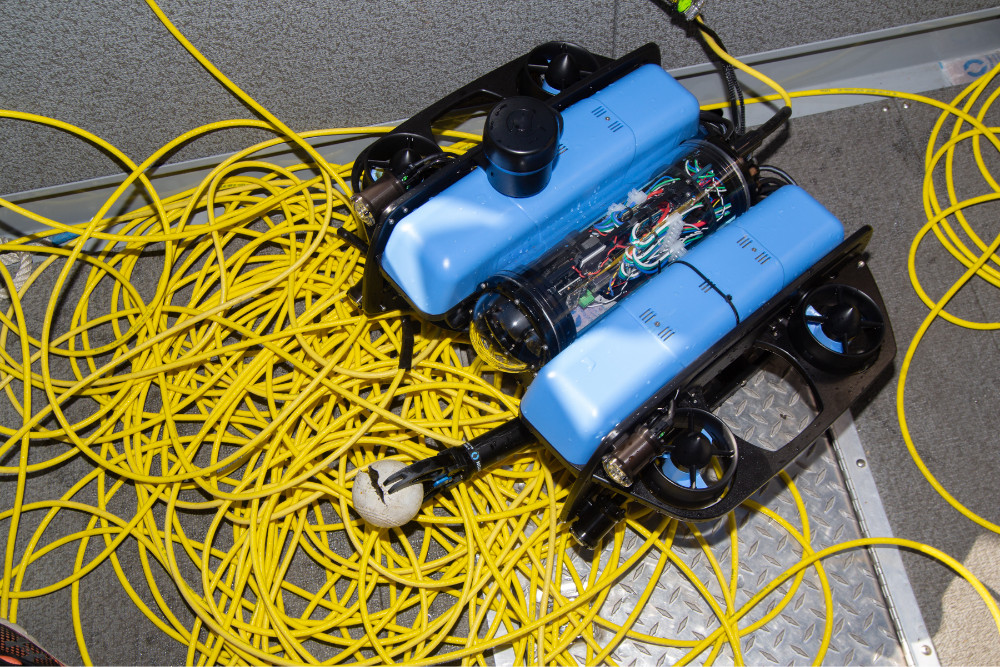

Seed money from Jamie and Kathy bought a 21-foot outboard aluminum cruiser and the core of the operation, a light blue “remotely operated vehicle,” or ROV, equipped with what amounts to an oversized pair of pliers. Operated with a small, handheld device that looks and works just like a video-game controller, the ROV dives below the surface and grabs trash from the lake bottom.

Others at Tahoe, notably a group led by a local scuba diver, are also working to glean trash from the lake. Their efforts, however, are limited to areas close to shore and only up to around 25 feet deep. The Kopfs believe their organization is the only one in the West that’s using an ROV to retrieve lake trash at depths of up to 100 feet.

An Early Start

At 7:30 on a cool, cloudless morning, the foundation’s boat and another craft bearing a photographer are the only vessels visible on the vast, deep blue lake. The granite peaks of the surrounding mountains soar about the timberline as the boats race from Tahoe Keys Marina, on the California side, to Nevada waters just beyond the state line. (The foundation is licensed to operate in Nevada, but still must leap a few bureaucratic hurdles in California. The Kopfs hope to be working in the Golden State by next year.)

—

This story first appeared in the August edition of Climate Magazine

—

Driving the lead boat is Scott Fontecchio, a robotics expert and retired Tahoe business owner who is now the foundation’s operations director. While he steers the boat, Operations Assistant James Tisdell prepares the ROV, a model BlueROV2 manufactured by a company called Blue Robotics, to go underwater. His pre-dive procedure includes using a vacuum pump to check for leaks; if water were to seep into the ROV, it could foul the electrical system and a $20,000 piece of equipment could go belly-up.

Lindsay Kopf, meanwhile, sits opposite Fontecchio and describes how she came to be the foundation’s executive director. Two years ago, she was working as the compliance officer for various car dealerships, including the Kopf family’s Boardwalk Auto Mall in Redwood City. Her job focused on making sure people observed governmental regulations and other rules covering all aspects of the business. That sometimes led to unwelcome conflict. As Lindsay says, “People don’t like to be told when they’re doing something wrong.”

When Jamie and Kathy approached her, she thought, “Hmm. Work in a stressful job where people hate to see me come around, or live at Tahoe and try to do something good for the world?” She’s glad she chose the obvious. “I don’t have to be rough and tough anymore,” she laughs.

Crew-cut and clad in shorts and a T-shirt, Fontecchio shifts to the back of the boat and carefully slips the ROV into the water. Floating on the surface, it looks for all the world like a very expensive bathtub toy. “In a very big bathtub,” Lindsay quips.

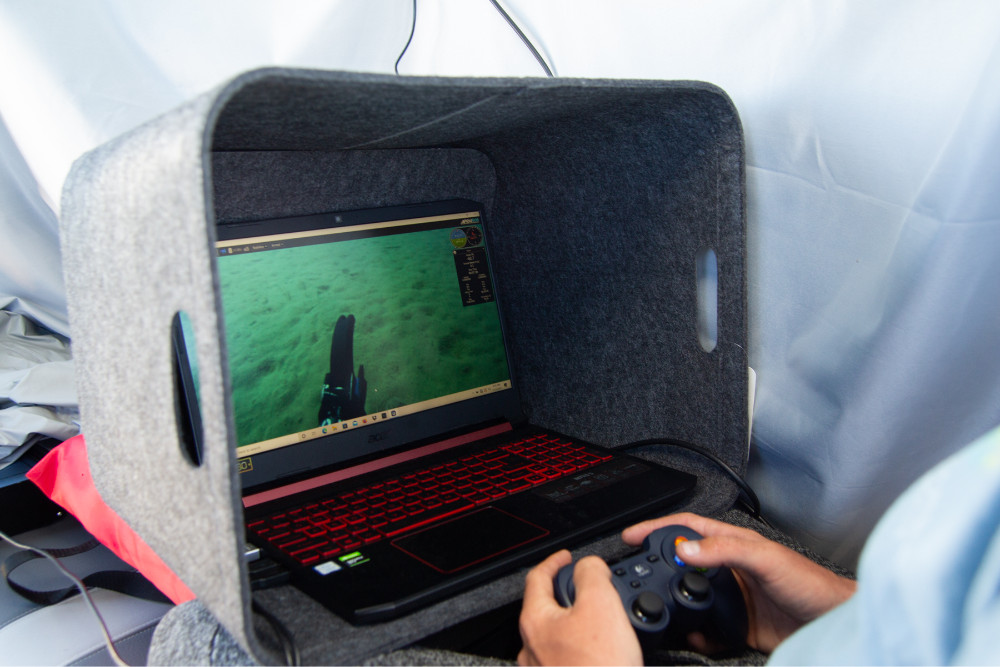

Attached to the ROV is a 300-meter-long yellow cord that contains the eight wires connecting the device both to the controller and a laptop that displays the video images the machine transmits as it descends and then hovers above the lake floor. As Fontecchio pulls the cord from a large spool and feeds it into the water, he looks exactly like the fly fisherman he is. Tisdell sits amidships under the boat’s canopy, facing the stern and gazing at the laptop, whose stiff, gray fabric hood blocks the daylight so he can see the screen.

Powered by a lithium-ion battery, four small thrusters move the ROV up, down and around as Tisdell manipulates the controller. The underwater apparatus heads straight for the bottom, 73 feet down. There, it will cruise at 1.5 meters per second, a foot or two above the lakebed to avoid stirring up clouds of sediment.

Deepwater Angling

Now, the search begins. In a sense, it’s just high-tech fishing, with a light and a video camera instead of a sonar-based fish-finder. (The foundation recently obtained sonar equipment, which will be employed in deeper water too dark for the videocam.)

During the five days a week when the boat is operating, Tisdell logs every “catch” from the 6- or 7-hour voyage. On a recent day, the take included a plastic cup, two pairs of sunglasses, a hair scrunchie, a watch band, scraps of cardboard and a large, red tarp, presumably a boat cover. Jamie says sunglasses and baseball caps are the items most often found. Perhaps the strangest discovery: A lawn mower. That led to a joke about fishing for dorado but catching an El Toro.

The team also frequently hauls up small, personal video cameras. Tisdell says they’re his favorite finds, explaining, “We get plastics, batteries and electrical components all at once.”

On this warm Friday morning, with the boat anchored and the ROV sending its video images, the pickings at first appear slim. The machine glides through the deep, displaying only pictures of the sand below. Short, irregular ridges make the lake bottom appear a bit like the surface of the moon. Then, finally, a small dark spot shows up on the computer screen. Tisdell directs the ROV closer, and in this land of towering lakeside casinos, the team anticipates a payoff.

No dice. It’s a pinecone.

On the one hand, it’s disappointing because it isn’t trash. On the other, it’s reassuring because the cone is part of nature. It will stay.

The hunt resumes. A minute or two later, the video stream reveals a small, white sphere, settled against a log. There’s just one problem. Beside it lies a jumble of rope that could snare the ROV’s cord.

“Too small – throw it back,” Tisdell says.

“Catch and release,” laughs Fontecchio, the fly fisherman.

Then they reconsider. Tisdell maneuvers the ROV to the other side of the log. Now the target sits between the log and the rope. Fontecchio encourages Tisdell to try if he thinks it’s safe.

“It’s going to be a tough grab,” Tisdell muses aloud as he lowers the ROV from above the log. Nudging the controls to squeeze the mechanical jaws, he eases the object from the floor of the lake. When the ROV surfaces, it’s grasping a slashed, rubber-covered baseball.

“I can’t believe I got that,” Tisdell exclaims.

“Nice job,” says Fontecchio, in a genuinely congratulatory tone that nonetheless implies they do it all the time.

And, generally, they do. By Fontecchio’s estimation, they’ve come up empty just once in two years. “But that’s good news,” he says of being skunked. “It means there’s not a plethora of garbage down there.”

Still, there’s enough to bother not just Fontecchio, Tisdell and the Kopfs, but others from the Peninsula who call Lake Tahoe their second home.

“It’s the place that I go to for peace and quiet and nature,” says Susan Kimmel, who with her husband Brian owns Clock Tower Music on Laurel Street in San Carlos along with a house near Tahoe’s North Shore. Kimmel has been going to the lake regularly since her youth in the late 1970s. Lounging in the water, she says, is “just like being a kid again. You’re out there just splashing around and having fun.”

Dwindling Clarity

With that in mind, she’s concerned about Tahoe’s water quality. “It’s incredibly important that the lake stay the way it’s been over all these years,” she says. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reports that the lake’s clarity has declined by around a third since 1968. According to a recent article on SFGate, scientists mainly blame sediment carried by melting snow from the mountains that ring the lake. Despite a reported $2.6 billion thrown at the problem over the last 20 years, annual measurements during that time show average visibility leveling off at between 60 and 70 feet below the surface, compared with 100 feet more than a half-century ago.

Even so, San Carlos engineer Fernando Bravo says the Tahoe Basin “feels like paradise.” Bravo enjoys hiking and mountain biking, as well as playing golf on the region’s many courses. He especially likes to swim in the Trans Tahoe Relay, an 11.5-mile race from Sand Harbor in Nevada to Dollar Point in California. Sponsored by San Francisco’s Olympic Club, the event last year reportedly drew more than 1,200 competitors.

Bravo says his favorite part is the last leg, where the water gradually becomes shallower and the lake floor emerges into view.

“As you come in, the whole bottom of the lake just becomes clear,” he says. “It’s just such a beautiful transition.”

From time to time, Bravo says, he has seen sunglasses, plastic bottles of sunscreen and other refuse on the lakebed as he has finished the race. He thinks it detracts from the experience.

“It happens in the forest, as well,” he laments. “Any time I see debris, I just feel so bad because it’s such a beautiful environment that you want to keep it pristine.”

Informed of the foundation’s work, Kimmel and Bravo immediately offered to volunteer. “I love lakes,” Bravo says. “And the Tahoe lake is just one of our world’s most valuable treasures. We want to maintain it for our future generations. It’s wonderful what they’re doing.”

Volunteers — and money — will be needed for the foundation to reach its ambitious goals. Soon, Lindsay wants to acquire an additional two boats and ROVs, and hire two more crews. The foundation’s webpage, www.restoremylake.org, reports $60,000 in recent contributions. Come this November, when operations shut down until the spring, Lindsay will switch into fundraising mode.

She estimates that, ultimately, the foundation’s mission to clean every navigable lake in California and Nevada will cost millions. According to various sources, California holds more than 3,000 lakes. Nevada has 36, including Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the U.S. (The foundation might get by with a vacuum cleaner on the cracked, muddy bed of Lake Mead, whose shrinking waters have reached a record low.)

Climbing Uphill

Just tidying Tahoe is a Sisyphean undertaking. In Greek mythology, a king named Sisyphus (SIS-a-phis) was sentenced by Zeus, the chief god, to roll a boulder up a hill in the underworld, only to watch it tumble back so he could push it up again — for all eternity. Lindsay has divided Tahoe into a huge grid and marks off each square as it’s cleaned. Still, in the lake’s own watery underworld, debris settles almost as quickly as the foundation can pick it up. Says Jamie: “This is going to go on forever.”

No doubt it will, if a sizable number of Tahoe’s 15 million annual visitors keep strewing their garbage. San Francisco television station KRON reported on July 6 that the annual, all-volunteer Keep Tahoe Red, White and Blue Beach Cleanup collected 3,450 pounds of rubbish the day after the Fourth of July.

Last May, another group called Clean Up the Lake said it had finished the initial segment of a planned circumnavigation of shallower waters along Tahoe’s shoreline. On 189 expeditions covering 72 miles, scuba divers retrieved nearly 25,000 pieces of litter that together weighed approximately the same number of pounds.

The daily breeze helps the trash find the lake. Famed for its calm surface and excellent water skiing in the morning, Tahoe gets windy and choppy by midafternoon. The wind blows articles from boats, beaches and lakeside picnic areas into the water. Beyond paper plates, napkins and newspapers, plastic items such utensils, cups and bags make for a growing concern.

Unease Over Microplastics

Wind, waves and sun all cause plastic to degrade. As they weaken, plastic sunglasses and beer cups, for example, can break into tiny chips called “microplastics.” (Certain microplastics, such as the tiny beads used in cosmetics, are manufactured.)

Microplastics contaminate not only water but also the land and the air. According to the British scientific journal Nature, microplastics have been found in the atmosphere, as well as destinations as diverse as shellfish, beer and rainwater. In 2021, environmental scientists led by Dr. Albert Koelmans at a university in the Netherlands estimated that, in the worst cases, certain people might be eating and breathing the equivalent of a plastic credit card every year.

That said, the jury’s out over whether microplastics are harmful to humans. As of 2021, the only widely known published studies involved mice, with artificially high exposures. But with worldwide plastic production expected to double by 2050, Koelmans has described the potential problem as “a plastic time bomb,” adding, “If you ask me about risks, I am not that frightened today. But I am a bit concerned about the future if we do nothing.”

Indeed, doing nothing may prove a poor choice. From Lake Tahoe’s only outlet, the Truckee River rolls northeast and provides 85 percent of the Reno area’s drinking water before emptying into 112,000-acre Pyramid Lake on the nearby Pyramid Lake Indian Reservation. In addition, both the river and Pyramid Lake support irrigation. Beyond that, the lake, home to the famed Lahontan cutthroat trout, also brings considerable revenue from visiting anglers, according to Donna Marie Noel, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe’s natural resources director.

Whether it consists of miniscule scraps of plastic or baseballs or flipflops, Lake Tahoe’s growing garbage pile may threaten not only an environmental gem, but also the area’s lucrative tourism economy. In 2019, U.S. News & World Report ranked the entire lake region as the nation’s third-best small town to visit. That opinion may not last if increasing numbers of tourists double as chronic litterbugs. But even as more people descend on the Tahoe Basin, in many cases leaving their rubbish behind, the Kopfs’ foundation and other volunteers will follow and smarten things up.

And who knows? Kathy Kopf may finally find her hat.

More information about the Restoring the Lake Depths Foundation: www.restoremylake.org