Every year, retired newspaperman Bill Shilstone tells himself the same thing.

“I always say I’m never going to do this again,” he says of the holiday letters he drops off at the Palo Alto post office. The trouble is he’s managed to make the droll updates focusing on the doings of his eight grandchildren entertaining enough that he has amassed an array of non-social-media likes and followers.

A quiz. Funny quotes from the grandkids. A family scorecard that toted up weddings, engagements and new arrivals (one each) versus trips to Europe (zero). He’s used them all to elevate his annual communication about everything Shilstone into a distinctly amusing missive.

“People look forward to the letter,” he admits. “So, year after year, I’ve got to come up with some angle.” And as his wife, Judy, reminds him, he can’t disappoint his fans by stopping now.

Shilstone isn’t the only one who might be battling writer’s block this time of year. Across the country, a blizzard of annual cards and letters will go out in coming weeks, many of them addressed to the Big Guy up north. Not just for Santa, but for many people, however, it will be the one time during the year when they receive an individually addressed, stamped letter. It’s a bit ironic, in fact, when so many struggle to come up with a gift for that person who “has everything” that the lowly letter could be a master stroke of the pen, unrecognized.

Spreading Happiness

Only 11 years old, Emilia Priest, the daughter of Sequoia High School Principal Sean Priest, is wise to the value of letters and sends out five to 10 a month. She picked up the practice because “when I read a letter, I feel happy and I want people to feel the same way. I like writing thank-you notes and birthday cards.”

Ideally, a mailed letter produces a response in kind—a letter in return, a note or at least a call. Emilia recently sent letters to Starbucks and the makers of Cheez-Its and Oreos, and was eagerly waiting to hear back. She told Cheez-Its that “I was like their number one fan” and was eating Cheez-Its while she wrote. “I’m really waiting for those companies hopefully to send me back something,” she adds.

Letters of important people can live on in biographies or command huge sums at auction. Letters have inspired scores of song titles (“Love Letters Straight from Your Heart;” “I’m Gonna’ Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter;” Elvis Presley’s hit, “Return to Sender;” and Bob Dylan’s “Dear Landlord,” to name a few). Handed down as family heirlooms, letters can even attain a kind of immortality. Sometimes the most treasured are also the most private—love letters that allow grown children to eavesdrop on their parents’ blossoming romance.

In the case of one couple, a larger audience might get to hear, as well.

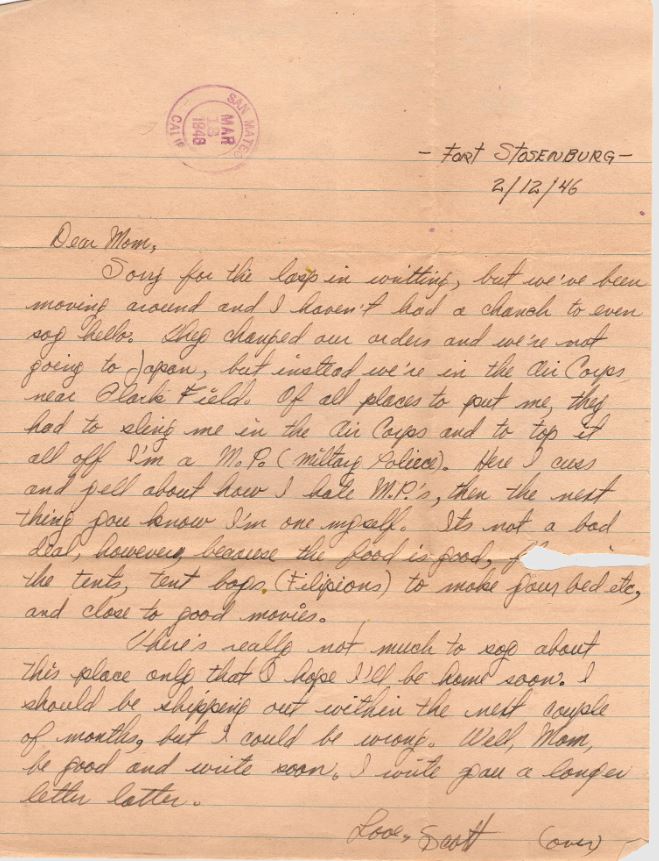

Shilstone’s younger brother, Mark, and his wife, Adrienne Laurent, grew up in Redwood City a few blocks from each other and met in college. Mark went on to a career in theater and taught speech while Adrienne became a television news anchor. Now living in Salinas, the couple has Adrienne’s father’s World War II letters to his mother, and Mark’s father’s letters to his future wife. They are assessing whether to turn them into a theatrical production entitled “Letters from Our Fathers.”

If it were to be produced, Adrienne would read from her dad’s Navy-censored letters about shipboard life. Mark would be the voice of Burton Shilstone, a railroad sales rep who was courting the girl who in 1939 became Suzanne Shilstone. The challenge, Mark says, will be to contextualize the letters with music from the time and maybe digital images to make them compelling theater for the public instead of just interesting memorabilia for the family.

Those letters, of course, rose from a pre-internet age, which lacked the instant efficiency of firing off an email or a text, plus the variety of methods social media offers for easy communication. In the World War II era and for decades to come, long-distance calling was so expensive that people wrote letters instead. Today, in contrast, who leaves the house without their phone?

Changing Times

Ken Perkins, a member of the Sequoia Stamp Club in Redwood City, draws an analogy between the factors that long ago made letter-writing—and later electronic communication—catch on.

“The advent of the Penny Post in Britain in the early 19th century, which coincided with Britain’s issuing the world’s first postage stamp, resulted in an immediate huge increase in letter-writing,” he says. “The pre-Penny Post rates, which were based on the distance the letter had to travel by mail coach, were terrifically complicated and very expensive. The Penny Post enabled ordinary Britons to write at least the occasional letter to friends and relatives every year.

“It strikes me that the development of email and its relatives, coupled with the ubiquity of smart phones, has caused a similar order-of-magnitude increase in person-to-person communications at the expense of the written version,” the Belmont resident continues. “I can now, for example, communicate with my son, who’s in Finland, in real time via either texting or phone call, at no charge [beyond the basic rate].”

For Jim Giacomazzi, 80, who grew up in the Salinas Valley, snail mail was worth the wait. His thrifty mother had lived through the Depression, but just preferred writing and receiving letters to talking on the phone. “We lived in a rural area, so our mail was delivered twice a week,” the Redwood City resident recalls. “Tuesdays and Saturdays were anxiously awaited because those were the days that our Star Route mail was delivered.” (“Star routes,” now known as “highway contract routes,” cover often-remote areas and are serviced by contractors to the postal service.)

When he went to college and then the Peace Corps, Giacomazzi responded to his mother’s weekly letters (although less often), with ones he thought were “rather mundane and uninteresting, but they must have meant a lot to her. While going through her things after she passed away, in a box along with a diary, I found that she had saved every letter that I had written to her.”

Giacomazzi went on to a 30-year teaching career at San Carlos and Sequoia high schools. Like Perkins, he also became a stamp collector. He nevertheless has reluctantly concluded that letter-writing is a lost art. Last year he bought his granddaughters writing paper, envelopes and stamps for their Christmas stockings, “but they still prefer to phone or use email to communicate. It seems that people today cannot spare the time or effort that is required to write letters.”

A Death Greatly Exaggerated

Not so, insist Gwen Gasque, owner of the 40-year-old Letter Perfect store in Palo Alto, and her employee, Sylvia Gleason, who has been writing letters since she was 5. Gleason started at the store as a customer and went on staff 14 years ago.

“Oh, letter-writing is thriving. Oh, yes,” she says. Customers buy not only specialty paper but also pens and ink so they can create calligraphy, combining beautiful paper and artistic writing. At the holiday season, Gleason says, the store sells most of its stationery and all its bordered papers. She adds, “We even have kids 10 to 12 who order their own personalized stationery.”

Marilyn Territo of Redwood City is naturally gifted with beautiful handwriting, and she takes letter- and note-writing to a high art. Always on the lookout for pretty, blank cards, she wields one of her three-dozen calligraphy pens to craft a personal note—even when she’s just paying a bill. A store clerk looking at one of her checks once told her she should create a new font for Microsoft.

She often hears from people who want to send a thank-you note for her own virtuosic thank-you notes. The husband of one of her good friends keeps a box with all the cards he has received from Territo. So does a local attorney, who tells her that when he’s having a down day, he pulls out one of those cards ornamented with flowery writing and “it makes him feel good. … It’s just what I do,” says Territo, whose sister, Paula Uccelli, is also a prodigious card-sender.

—

This story first appeared in the November edition of Climate Magazine

—

“I don’t care if people think it’s cumbersome even for them to get it,” Territo, 77, says. “I want to do it. Usually, I do get a good response from it.”

The arrival of electronic communication was a motivator for her. When texting and email came on the scene, “I was horrified to see that people were writing complete sentences in lowercase. I know a lot of people don’t put periods in their text messages. But I did not want to lose the art of proper writing in the Queen’s English. … I knew if I didn’t write the way I wanted to write that I would lose that.”

She recognizes, with a laugh, that “There’s a whole younger generation that probably can’t read my handwriting. I mean, let’s face it. They can’t read it.”

Problem Penmanship

By contrast, former State Senator Jerry Hill’s handwriting was never something to write home about.

“I’ve always been somewhat embarrassed by my handwriting,” he says, and that included his signature, which he didn’t think looked very professional. But after 30 years signing “Jerry Hill” to thousands and thousands of letters and documents, “My ‘Jerry Hill’ has a flair to it today that it didn’t have.” The signature, though, “is the only thing that got better.”

A former San Mateo mayor and a county supervisor, Hill says he “read every letter that came in … and some of the handwriting was not the easiest to read.” He’s not one to mourn the “death” of the old-fashioned letter and considers electronic forms of communication much better at letting elected officials hear from larger numbers of constituents.

“I don’t see that we have lost anything other than we have lost the reflective nature of someone sitting down and writing a letter,” he says. “I believe it can be a more thoughtful process than doing a quick email.”

For historians, the switch to electronic communication has complicated their task. A letter is tangible—as opposed to a tweet or an Instagram that vanishes like a dandelion puff. A letter is also a valued primary source that documents what someone said, and is not filtered, commented on or subject to massive re-tweeting, notes Mitch Postel, president of the San Mateo County Historical Association.

And there’s often not much wheat among the digital chaff.

“We know that there are emails and tweets and that kind of stuff that do have consequences and do stand out,” he says. “I think the challenge for historians is that, maybe in the old days, you’d look at 100 letters and you’d be able to pick out 10 [that had significance]. … But with emails you can go through a couple thousand emails and not find anything of consequence … because of communication that is so voluminous now.”

Coming off a week’s vacation, Postel was plowing through his inbox. “And they even tell you what to say. You come to the end of an email, and they give you suggestions how to answer it: ‘Okay!’ ‘That’s fabulous!’ … The response is there. All you have to do is hit the thing—‘Absolutely!’—and then you’re finished with it.” By contrast, in the letters of old, long periods of time went by before people saw each other, so they labored over their comprehensive updates.

Good Therapy

Several people interviewed for this story remarked on the emotional power of letters they’d received. Redwood City Vice Mayor Diana Reddy says getting a note in the mail from a resident is “very personal and it represents the time that someone took to write that message and put a stamp on it and put it in the mail. It’s like a small gift.”

On the advice of a mentor when he started his teaching career, Sequoia High School’s Sean Priest started a file of letters from students, families and colleagues. “And am I glad I did,” he says. “It’s sort of a ‘break-glass-in-case of emergency’ resource when I need a shot of affirmation. Revisiting people’s kind words has lifted many a dark cloud over the years.”

Menlo Park resident Jane Molony had been a letter-writer for many years, but her motivation intensified after she and her husband lost their first child through a miscarriage. “Several people,” she says, “took the time to write a note and each note kind of made it better.… That got me going on [sending] not only letters but get-well and sympathy cards.” When friends are having a rough spell, she puts them “on card therapy.”

Molony loves going to the mailbox to see if there’s anything handwritten. “I call it ‘my good mail’—something besides the requests for money or junk mail or whatever.” The Molonys send a “spring letter,” when life isn’t as hectic as at the year-end holidays. Molony says the couple always gets positive feedback.

Perhaps with technological changes, it may be all over for the old-fashioned letter. But not for everyone. “It may be passé,” says Molony, “but it’s always nice and it’s always appreciated.…It still matters.”