By Kevin Kaatz

The year was 1990, and the man standing before the front desk at the Redwood City Library didn’t want to give his name. He handed the librarian, Jeanne Thivierge, a cardboard box that he said contained more than 2,000 letters and financial documents. He told her the management of Wells Fargo Bank had asked him to destroy them, but he thought they might have historical value.

He was right.

At first glance, the paper records looked nothing more than ordinary—receipts, tax bills, powers of attorney. But then there were the letters. As Thivierge read them, a rich history began to unfold about a remarkable man who consistently went out of his way to help his neighbors, American citizens of Japanese descent who had been removed from their homes and businesses in Redwood City and sent to prison camps early in World War II.

FDR’s Exclusion Order

On February 19, 1942, just a little more than two months after Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. Through broadly worded, the edict was employed to send West Coast residents considered Japanese—including U.S. citizens—far inland for presumed security reasons.

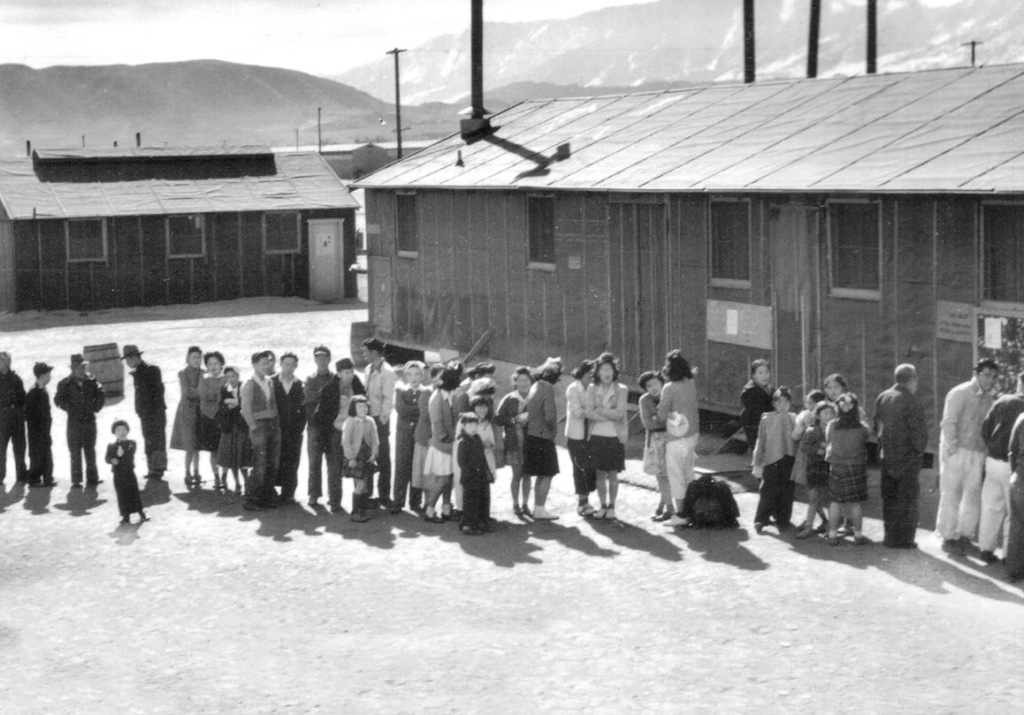

They were given just a few days to sell, rent or simply abandon their property, including houses, shops and small farms, before reporting to “assembly centers” at locations such as the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno. From there, they were shipped on trains to 10 detention camps at remote points in California and Utah as well as Arizona, Wyoming and Arkansas. The lucky ones came home starting in 1945. Others never came home at all.

For many in Redwood City, a man named J. Elmer Morrish was their banker. A vice president of First National Bank (later Wells Fargo) at the corner of Broadway and Main Street, Morrish was widely known among local Japanese-Americans. Before being shipped out, numerous clients assigned him control over their accounts so he could pay invoices—especially tax bills—that would enable them to keep their homes and businesses.

Over the course of three years, from 1942 to 1945, Morrish did that and much more. The correspondence in the box revealed relationships that extended far beyond routine transactions. Often, the letters demonstrate the trust Morrish had earned and the affection he shared with his neighbors.

Many Japanese-Americans in the area grew flowers, especially chrysanthemums. Minutes from a special meeting of the Peninsula Flower Growers (headed by a man named William Haruo Enomoto) gave Morrish full power to take care of the members’ businesses, except for conveying or mortgaging them. The document was signed on March 24, 1942, a month-and-a-half before Redwood City’s Japanese-American residents were forced out. Even though Roosevelt’s decree referred only to “any and all persons” who could be removed from “military areas,” clearly the flower farmers knew what it meant.

Other letters were more personal. On June 26, 1942, a Miss Adachi sent this note to Morrish: “We at Tanforan are fine and looking forward for brighter days. Deep in our hearts there is that deep appreciation for everything that you have been doing for us, but very hard to find the right words to express this thought.”

Two years later, on June 23, 1944, Morrish wrote to Miss Adachi in what appears to have been a fond and continuing exchange. “I have heard somewhere that you have married,” he said, “but I hardly believe that is true because you haven’t written to me to ask if it was all right.” Composed decades before emojis, the line can only be assumed to be playful. Morrish wrote again in October, saying he hoped all was well and that he had not heard from Miss Adachi in months.

Still more communications were serious, even urgent. Morrish often kept track of people’s property, monitoring empty homes and renting them when he could. Occasionally, there was vandalism. Regarding one such occurrence in November 1943, a frantic Mr. Nakano sent Morrish a list of personal possessions in his house along with a drawing of where things were, and asked him to check his belongings.

Mr. Nakano wrote, “Wife was quite alarmed over the incident because of some of the things she left at home that we should have taken greater precautions of security for them but at the time of evacuation our activities were so jumbled and curtailed by the thoughts of impending evacuation that we didn’t do many things that we should have done to protect our property.”

Decades-Old Memories

In oral histories recorded in 2003, members of Redwood City’s Japanese-American community remembered Morrish, who died in 1957, with respect and thanks.

“He was a prince of a gentleman,” said second-generation nurseryman Harry Higaki, who eventually resided in Hillsborough and lived to age 101. “He personified the meaning of the word ‘gentleman’ because he offered all of this to us. …Those were the times of tension and, I guess, you would say, discrimination. But yet he rose above that. He treated us the same, before and after. I just couldn’t believe how he was so kind and generous in helping our family. … I’ll never forget him. [I am] eternally grateful to him.”

A woman named Ruby Inouye told an interviewer, “Mr. Morrish took care of everything … He did a lot; [it was] personal—I mean, it was outside of the banking thing … He took it on his own to see what was going on at the nurseries …”

Added another woman named Teru Tamura Mitsuyoshi, “My dad always mentioned Mr. Morrish and had nothing but good things to say about him and how helpful he was. … He was always so good to [people].”

Appalling Conditions

The same could not be said of the U.S. government when the internees arrived at the camps. There was window dressing—a band played as they climbed down from the train in Topaz, Utah—but the ensuing reality was anything but melodious. At Topaz, what was to pass for housing hadn’t yet been completed. When it was, it consisted of tarpaper shacks built hastily with freshly cut wood that shrank over time, causing structural problems. Many accommodations lacked roofs and working bathrooms. People became ill with colds, the flu and more life-threatening illnesses, and the facilities weren’t set up to provide adequate medical care.

Then there were the not-so-subtle ironies. While living in converted racehorse stalls at the Tanforan assembly center, the detainees were encouraged to buy U.S. war bonds. The advertising mentioned that the funds would not only help the country fight the war but also keep the assembly centers going. Meanwhile, tax bills reminded people that they were paying government officials to retain homes and businesses from which they had been evicted.

Coming Home

Finally, in early January 1945, the government started allowing its citizen-prisoners to return. Morrish wrote that housekeeping jobs around Redwood City were plentiful but housing itself was scarce. He suggested that people wait “a few months.” Even those who owned property found difficulty removing tenants and squatters.

Over the next few months, however, residents began trickling back. The correspondence with Morrish stops by mid-1945, around the time the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August. Japan officially surrendered on September 2, 1945.

From all that seems to be known, Morrish may have done his work quietly. It was 1956 before Mayor Bill Royer declared him Redwood City’s Citizen of the Year. Even then, the honor came for Morrish’s leadership of the chamber of commerce, the Kiwanis Club, the community chest, the YMCA and a regional bankers’ association. No official mention has been found of his help to the city’s Japanese-American community.

But people remembered. In 1957, local Japanese-Americans pooled their money and bought Morrish an around-the-world ticket for a long tour that included Japan, where their family members met him and showed him the sights. Not surprisingly, the nonstop letter-writer mailed back numerous accounts of the trip.

The extended sojourn represented more than just a warm gesture. In a way, it was a culmination. Less than two months after he returned, Morrish died on October 31, 1957. He was 71 years old.

His memory remains alive in the Morrish Collection at the Redwood City Library’s Karl A. Vollmayer Local History Room. In 2003, Jeanne Thivierge—the librarian who had accepted the mysterious box more than a decade before—and Gene Suarez, another library employee, organized a memorial and the oral histories of local families.

It’s often said there is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for a friend. True, J. Elmer Morrish didn’t make the ultimate sacrifice. But for three years in a tumultuous time, softly, deftly, unassumingly, he simply did what needed to be done.