I eagerly awaited a recent television documentary about Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman named to the Supreme Court of the United States. I fully expected to hear the narrator mention that Redwood City played a role in O’Connor breaking the so-called “glass ceiling.” Not a peep. Instead the PBS documentary focused on jobs she didn’t get in her early career. Needless to say I was disappointed, but I will say it anyway. I was disappointed. O’Connor started her legal career in 1952 when she was hired by San Mateo County. It must be conceded, however, that when she broke gender barriers, “glass ceiling” literally meant a skylight.

Sandra Day graduated from Stanford in 1952 in a class that included William Rehnquist who would go on to become Chief Justice. The class also included John O’Connor whom she married six months after graduation. At the time, the only jobs in law offices open to women were apparently for office secretaries. In a 1999 interview, O’Connor said she was told at one firm “We’ve never hired a woman, and frankly, I don’t think we ever will.” In her 2004 commencement speech at Stanford, O’Connor had more to say about the gender barrier that stood in her way in private practice. She said discrimination was “more easily hurdled in the public sector” where she found “encouragement from good mentors who were more genuine.”

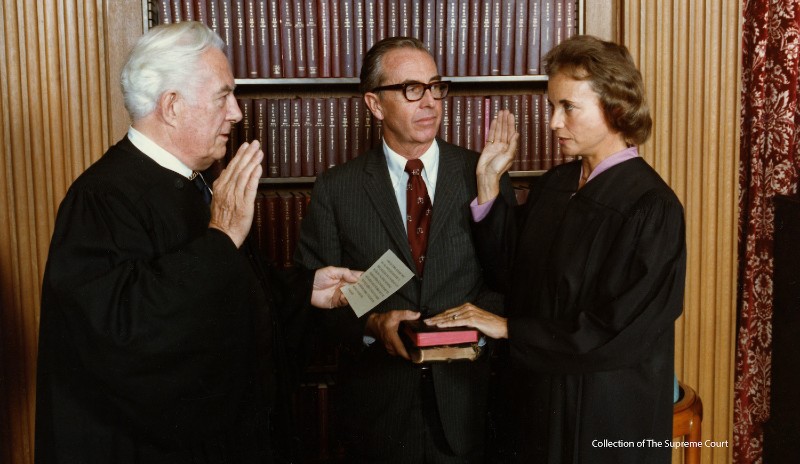

Mentoring a Future Judge

Those mentors included San Mateo County District Attorney Louis Dematteis, whose prestigious career garnered headlines for his crime-busting efforts against entrenched illegal activities, including gambling. He was also known for fairness in hiring, having already added a female attorney to his staff. In a television interview in 2002, O’Connor, who served on the Supreme Court from 1981 to 2006, called Dematteis “a wonderful man” who “once had a woman on his staff, a lawyer, and I thought, ‘well, if he could have one, he could have another.’”

Dematteis’ son Lou said his Italian-American father knew what being discriminated against was like. A Dematteis family treasure is a framed portrait of O’Connor that was presented to Lillian Dematteis. It is signed “For Lillian Dematteis, whose husband gave me my first job as a lawyer.”

Another of O’Connor’s mentors was Keith Sorenson, her immediate supervisor. Then deputy district attorney, Sorenson moved up to DA when Dematteis became a superior court judge. O’Connor resigned from her job in the county courthouse in Redwood City in 1954 and moved to Germany with her husband, who was then a lawyer with the U.S. Army. Once in Germany, she became a civilian attorney for the Army.

Learning to Work Hard

O’Connor’s autobiography was published in 2002, but rather than a snappy legal phrase or pun, the book is entitled “Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest.” She grew up branding cattle on the family ranch in Arizona, an experience that developed her faith in hard work, eventually leading to securing a judgeship and election to the Arizona Senate.

Her friends from ranching days included the late Karma O’Dell, a member of a writing group at the Redwood City Veteran’s Center who passed away in 2008. O’Connor’s name popped up during a discussion at one session, according to a member of the group who quoted O’Dell as saying “Oh, I know Sandra Day. She’s just the nicest girl. Not stuck up at all! We went to school together and still write occasionally.”

A letter O’Connor wrote when she learned of Odell’s death is a cherished item in the writing group’s scrapbook: “We were good friends as children in El Paso. Although we did not often meet as adults, she was a cherished friend. She brightened many lives.”

In 2018 O’Connor wrote a letter addressed to her “friends and fellow Americans” in which she disclosed she was “diagnosed with the beginning of dementia, probably Alzheimer’s.” O’Connor, who was inducted into San Mateo County’s Women’s Hall of Fame in 2015, was born in 1930 on the 26th of March—Women’s History Month. She and her husband, who died in 1981, had three children.