By Jim Clifford

Eerily, the recent flu outbreak occurred during the 100th anniversary of the deadly “Spanish Flu” that devastated much of the world’s population during World War I. Redwood City, with a population of around 2,500 at the time, lost 10 men in the war, more than any city in San Mateo County. Nearly all died of the influenza.

In 1919 the Sequoia High School yearbook featured five pages about former students who served in uniform. Lloyd Thrush was among those who died in the influenza pandemic that claimed more lives than combat. Thrush, an Army captain, was described in the 1919 yearbook as “a superior student in all lines of school work.”

Thrush’s death was front page news in the Redwood City Democrat on Oct. 17, 1918. The paper reported he was the first former Sequoia student to die in the Great War. Three other Redwood City men died earlier in the war, one in the crash of his fighter plane, one from “disease” and the other from “pneumonia.” The use of such a non-specific word as “disease” gives the impression that authorities didn’t sense the horror of the flu or, if they did, didn’t want the public to know how serious the situation was, even though the same paper carried an ad for Foley’s Honey and Tar mix under a bold headline simply reading “INFLUENZA?”

Apparently, the only Sequoia High grad to die in combat was Army Corporal James Wilson, who was killed in the Meuse-Argonne battle in France, a major offensive in which 26,000 U.S. soldiers died. The local Veterans of Foreign Wars post bears his name.

According to the National Archives, the flu killed about 50 million people in 1918. The war claimed an estimated 16 million lives in four years.

“Within months, it had killed more people than any other illness in recorded history,” the archives reported in a summary of the deadly virus it said attacked one fifth of the world’s population.

“Some victims died within hours of their first symptoms,” the report said. “Others succumbed after a few days, their lungs filled with fluid and they suffocated.”

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, there were 53,402 American battle deaths in WWI and 63,000 non-combat deaths, most from the flu that came to be called “the Spanish Flu.”

Flu historian Diane Rooney, who lost a relative in the outbreak, was asked about the Spanish connection when she spoke recently at the San Mateo County History Museum. Spain, she said, was neutral during the war and was able to report on the pandemic without fear of military censorship.

“Most people,” she said, “assumed the flu originated in Spain, which was not the case.” According to Rooney, the latest theory is that the flu originated near Fort Funston, a training camp in Kansas, now known as Fort Riley, and was spread by American troops.

The title of Rooney’s talk was “And the Plague Broke Upon Them.” Indeed it did. Officials estimate that 25 percent of the population of the United States was stricken.

“The plague did not discriminate,” the National Archives said in its aforementioned summary. “It was rampant in urban and rural areas, from the densely populated East coast to the remotest parts of Alaska. In one year, the average life expectancy in the United States dropped by 12 years.”

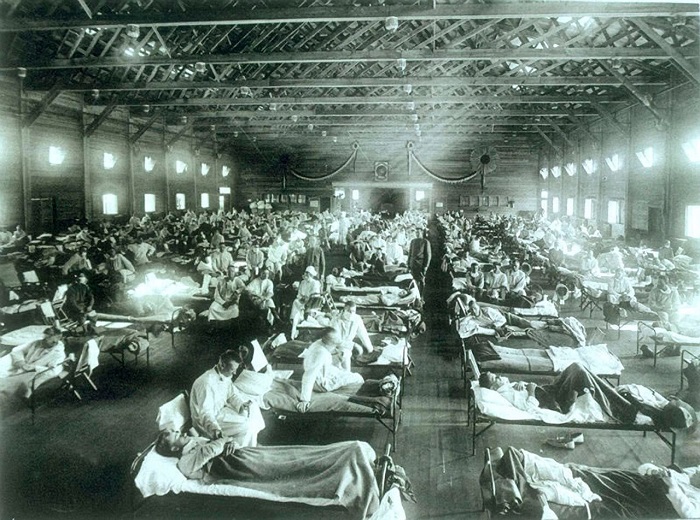

Surprisingly, young adults, usually unaffected by infectious diseases, were among the hardest hit groups. That segment of the population included soldiers, among them the soldiers at Camp Fremont, the sprawling Army training base at Menlo Park. In December of 1918, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that within six weeks after the outbreak there were 147 deaths at Camp Fremont among 3,000 cases. The publication emphasized that the estimate was “conservative.”