By Cassandra Sweet

Throughout the Peninsula and into the South Bay, an anti-growth backlash appears to be gaining momentum. It has emerged in a variety of venues and jurisdictions, in many cases in the form of ballot box urban planning. The efforts have put local leaders in a position of trying to placate residents who are actively resisting change, while working to speed development of much-needed housing and responding to the constant demand for more office space.

Growth and all the issues that spin off from it will loom large in the coming Redwood City Council election. But the city is far from alone in dealing with the contending forces that are bringing so many good things – and so much controversy – to community after community.

In November, voters in Mountain View will decide whether Google and other large employers will have to pay a “head tax” on their employee head count, while San Mateo residents may be asked to approve or reject a proposal to restrict the size of all new buildings for years to come. These initiatives follow an ordinance the Palo Alto City Council adopted last April to limit new office development. That action, in turn, spurred a residents’ group to propose a further reduction, which may also appear on the November ballot.

The growth that some view as cause for concern and others see as cause for celebration isn’t slacking off. Far from it; hence, the backlash. Amid the noise is a growing concern that people may be taking the economic good fortune for granted and could hurt low- and middle-income families and kill the proverbial golden goose.

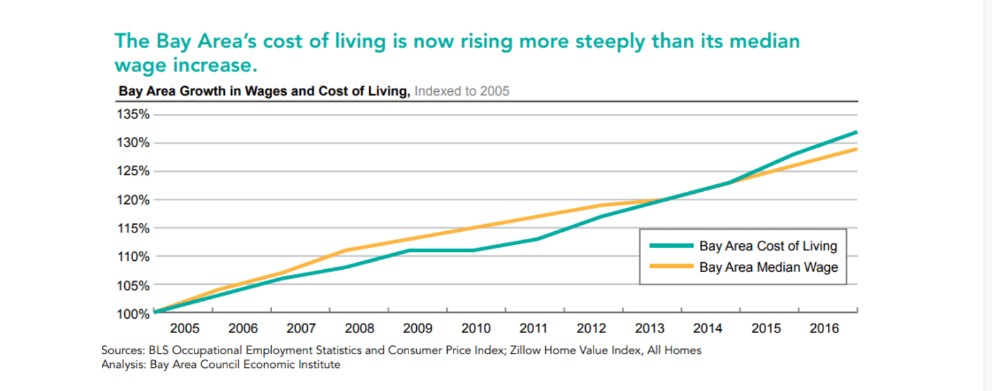

Indeed, the San Francisco Bay Area’s white-hot economy is growing faster than the U.S. economy as a whole, and it shows no signs of slowing down. The economic boost is creating a new world of jobs and opportunity, but it also is putting pressure on people who live on the Peninsula – or want to. Policy makers are grasping for ways to fix a housing crisis that has been decades in the making and seems to get worse by the day. Fierce NIMBY (Not in My Backyard) opposition to development adds a layer of difficulty to the problem.

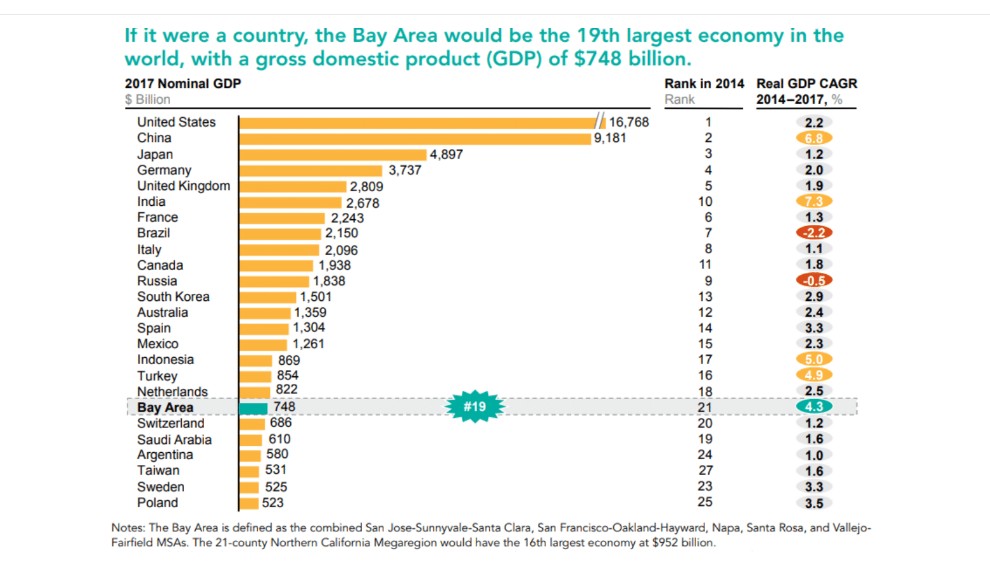

If the San Francisco Bay Area were a country, it would be the 19th largest economy in the world, with a gross domestic product of $748 billion, just after the Netherlands, and ahead of Switzerland, Saudi Arabia and Argentina, according to a recent report by the Bay Area Council.

Since 2011, the Bay Area’s nine counties have added 630,000 jobs. During the same period, however, local governments issued building permits for just 146,000 new homes. That’s 4.3 jobs per housing unit, far short of the 1.5 ratio that experts say is necessary to ensure everyone has a place to live.

Bay Area housing prices have skyrocketed out of reach for most people over the last few years. The median home price in San Mateo County is $1.6 million, up 8 percent from a year ago, according to the California Association of Realtors. Just 15 percent of the county’s residents can even afford that amount, because it requires annual income of at least $326,000 and monthly payments of more than $8,000, according to the group.

The average rent in the county for a three-bedroom apartment is more than $4,250, according to rentcafe.com statistics.

Rapid economic growth also has affected commercial office space, for which demand vastly outpaces supply, with only a 7 percent vacancy rate. Commercial rents in Menlo Park and Redwood City were nearly $6 per square foot earlier this year, 26 percent higher than nearby cities, due to high demand and a lack of available supply, according to a recent report by Avison and Young.

The shortage of available office space has put tremendous pressure on rents and has had impacts on small businesses that have seen dramatic rent increases, just as in the housing market.

In San Mateo County, 72,800 new jobs were created from 2010 to 2015, but only 3,844 new housing units were built, exacerbating the housing shortfall and creating a 19-to-1 ratio of new jobs to new housing, according to the group Home For All.

These pressures formed the backdrop July 16 for a highly charged San Mateo City Council meeting, where council members deliberated in front of a packed room over how to handle a residents’ proposal that would extend a 27-year-old height limit for new buildings for another 10 years.

Supporters of the measure collected enough signatures to qualify the proposal for the November ballot, but the measure had several legal and technical problems that prompted the City Council to defer action until the issues are resolved. The council plans to take up the proposal August 6, its last meeting before the deadline for deciding whether to approve it for this year’s election.

A few anti-development activists in attendance spoke about the need to keep San Mateo from changing. They were largely older, whiter and more housing secure than the dozens of young people who also attended the meeting and asked the council to kill the measure.

Susan Shankel, who supports the height-limit proposal, said she and her husband have lived in San Mateo for 26 years and don’t want it to resemble Manhattan. She and other development opponents repeatedly compared proposed developments to high-rise buildings in New York City and warned against the “Manhattanization” of San Mateo.

“Continued growth is unsustainable and building taller buildings is not the answer,” Shankel said.

The younger folks, many of them renters and “YIMBY” activists, (Yes In My Backyard), spoke passionately about how the lack of housing has ravaged their generation. They spoke of family and friends who have had to leave the area because of housing insecurity and how buying a house – at a median price of roughly $1.5 million – is out of reach. Rather than stop growth, the young speakers asked the council to address traffic by encouraging development of housing, offices and retail in areas that are well suited for growth, such as near transit hubs.

“My brother, my sister, my fiancé’s sister, the best man at my wedding, and three of my friends moved out because we’re not building enough housing here,” Kevin Burke, a young San Mateo resident, told the council. “If we don’t build more housing, more of my friends and more young people are going to be displaced from our city.”

Jordan Grimes, a lifelong San Mateo resident and member of Bay Area Forward, said that even though he works “in our booming technology sector, I can barely afford to live in the city that I grew up in.”

He urged the council to host a “thoughtful, intelligent discussion regarding our future, which all San Mateans deserve to be a part of,” and not let a small group of residents set policy. “Groups that routinely hold our council hostage to the whims of a few do not deserve your attention.”

Kelsey Baines, a young psychologist at the Palo Alto Veterans Administration Hospital, asked the council to allow higher-density housing, to combat homelessness. “The cause of homelessness is poverty and a lack of housing,” she said. “The solution to homelessness is housing.”

A San Mateo homeowner and mother of three spoke about the need to stem the outflow of teachers from city schools.

“Our district is bleeding teachers because they do not make enough to be able to afford the cost of living in San Mateo,” Jennifer Mayman said. “Building more housing is key in bringing down the cost of housing, and building high, dense housing close to transit is the smartest way to do it. When we impose restrictions on housing by measures such as height limits, we’re effectively saying that we want to exclude people from our community.”

Opponents were unpersuaded.

“I hope that no one believes that housing in Manhattan and Tokyo and other cities that have extremely high-density high-rise housing is somehow cheap,” Cupertino Council member Steve Scharf told the San Mateo council. “If you want to build affordable housing, you don’t build market-rate housing that costs $8,000 a month. You actually go out and build subsidized housing for the most vulnerable: for the teachers, for the service workers.”

In Cupertino, where the average home price is $2.4 million, according to Zillow, Scharf is fighting a proposed development that would add 2,400 housing units and 2 million square feet of office space, at the site of a vacant mall.

Mountain View is facing similar issues. But a pending proposal to make big companies pay a new head tax on every employee is a dumb idea, Palo Alto Daily Post Editor Dave Price contends.

Only $600,000 of the $6 million that the city would collect each year from the tax would go toward housing, which isn’t enough to make a dent in the crisis, he argues. Worse, the head tax would hurt low-wage workers, as it would create a disincentive for companies to employ them and an incentive to cut back on low-wage jobs and outsource them to an outside contractor or to automation.

“Head taxes aren’t anything new,” Price wrote in a recent editorial. “Chicago had one but decided in 2011 to eliminate it because it was, in the words of Mayor Rahm Emanuel, destroying jobs.”

Seattle recently adopted, then repealed, a head tax. The City Council last May adopted on annual tax of $275 per employee on large employers. The money would have gone to help the city house the homeless. A month later, however, the council reversed course and repealed the tax, under pressure from Amazon, Starbucks and other large employers.

The pressure is on in Redwood City as well, where job growth – from large employers such as Oracle, Electronic Arts and startups such as Box and Evernote — has outpaced new-home construction. And it’s not just tech companies that are adding jobs. Stanford University is building new office structures to accommodate 2,700 employees.

The pressure is on in Redwood City as well, where job growth – from large employers such as Oracle, Electronic Arts and startups such as Box and Evernote — has outpaced new-home construction. And it’s not just tech companies that are adding jobs. Stanford University is building new office structures to accommodate 2,700 employees.

Building new housing and other space near transit centers will be key to solving the housing problem without generating more traffic, according to Giselle Hale, a Planning Commissioner who is running in the November race for the Redwood City City Council.

“We need housing at all levels in order to retain the diversity in the city that we all value,” Hale said. “To get there, we have big questions to answer: What do we need from our infrastructure to make growth sustainable? Where should the growth go and how can we mitigate the impacts of traffic and parking? Whatever the solution, we must reduce traffic, it affects us all, daily.”

One example of this is the Greystar housing complex approved for construction along El Camino Real in Redwood City’s Downtown Precise Area, a swath of the city near the Caltrain station and far from single-family homes. The four Greystar buildings together would create more than 960 new housing units, thousands of feet of retail space and parking for several hundred cars and bicycles.

The new units will be nice, but pricey: studio apartments at Greystar’s 299 Franklin Street building start at nearly $3,000 a month. A two-bedroom can fetch nearly $7,000 a month.

The need for affordable housing is urgent, especially for low- and moderate-income families, said Diana Reddy, a social justice advocate who also is running for a seat on Redwood City council.

“The economic inequality causes me the most concern, not the growth,” she said. “When a city is not able to provide housing for its residents we need to consider out-of-the-box sorts of things to provide housing for people.

“Thousands of people have been displaced from Redwood City. The lower the income, the farther east and south they go. A lot of people who have had to leave are now living in Tracy, Livermore and Vallejo. People with lower incomes still have good jobs here, but their commutes are longer.”

Reddy noted the plight of low- and moderate-income parents who have been pushed out by high rents. Many of them work at big tech companies. Some who attend Cañada College sleep in their cars at school on weeknights so they can study rather than drive long distances every day to and from school.

San Mateo County experienced a net loss of more than 7,600 people from mid-2016 to mid-2017, accounting for more than half the county’s total net loss of residents since 2010, according to the U.S. Census. This happened even as births far outnumbered deaths and as more than 5,600 people from outside the U.S. settled in the county over the past year.

Adding affordable housing has been tough going, as neighbors fight to either block construction entirely or to reduce the size of new apartment buildings.

Habitat for Humanity’s proposal for a six-story apartment building at 612 Jefferson Ave. is a recent example. The project is planned with parking for 20 low-income families on a downtown lot zoned for dense housing and buildings up to 12 stories tall. Attorney Geoffrey Carr’s office is in a small building next door to the planned apartments, and he had filed an appeal to block the project. The City Council rejected his appeal and found that the project is consistent with the city’s Downtown Precise Plan and with state environmental rules. Carr sued to block the project, arguing that it violated the California Environmental Quality Act. The parties came to a settlement last month that will allow the project to go forward, but, prior to that, Habitat for Humanity had said the construction delays had increased the cost by nearly one third, to $17 million.

Promoting housing near transit is seen as one way to combat traffic congestion while helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. California is making headway in meeting its aggressive goals for reduction, according to a July report by the state Air Resources Board. But emissions from cars, trucks and other vehicles jumped by nearly 2 percent in 2016, after rising every year since 2013. At nearly 40 percent, rising emissions from transportation – the state’s biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions – could prevent the state from meeting its 2050 reductions goal.

A major cause of this is vehicle miles travelled, or VMT, a new metric used to evaluate the impacts of building projects. Enabling more people to live near transit hubs is one way to reduce VMTs and fight the rise in gasoline use. Many millennials don’t own – and don’t want to own – a car. Living near transit is important for the next generation, and it dovetails with local leaders’ choice to in-fill sparsely used land in downtown areas and near bus stops and Caltrain stations to simultaneously address the housing, traffic and greenhouse gas problems.

Older residents who bought their homes or small office buildings years ago benefit from the current scarcity of supply because it drives up the value of existing homes and commercial real estate. That, of course, leaves young people and newer transplants with fewer options for an affordable place to live.

The real estate market loves the Bay Area and its rising prices. With such a huge gap between supply and demand, prices are widely expected to continue to rise.

The greatest price pressure is on the lower end of the market. Since early 2016, the values of low-price tier houses have jumped 21 percent, compared to just 16 percent for mid-price tier houses and 12 percent for high-price tier homes, according to a May report by Paragon Real Estate Group.

Grouped together as “Silicon Valley,” Peninsula cities ranked second, behind San Francisco, in a global ranking by real estate market analysts Jones Lang LaSalle of cities considered the most likely to succeed in the short and long terms. The two Bay Area regions have the world’s largest number of startups and have also created the most tech unicorns — startups valued at more than $1 billion. They also have other qualities, such as innovation capability, talent, world-class higher education, and public infrastructure that will enable them to manage and benefit from the current rapid technological shift in the global economy.

Younger people and newer transplants are finding it tough going, and the high cost of housing is driving people away. In the last few years, migration patterns have turned negative and in 2017, the Bay Area lost more than 35,000 people, who left for other parts of California and the U.S, according to the California Department of Finance Demographic Research Unit. Some of those people are driving right back to Bay Area counties to work, in what are now called “mega-commutes,” journeys that take 90 minutes or more each way. Others are simply living in their cars.

“We don’t want to kill the goose that laid the golden egg,” said Rosanne Foust, president and CEO of the San Mateo County Economic Development Association, who also is a former Redwood City mayor and City Council member. “We want to keep the economy humming. That requires more housing and it requires everyone to be willing to give a little. It’s not going to get solved with one project, one development, in one community. It’ll require all folks to recognize that we need more supply at every income level.”

The upcoming November election could be pivotal for Redwood City and neighboring cities, as policy makers grapple with how to advance responsible growth against objections from residents who aren’t comfortable with the changes that have already been increasing densities on the Peninsula. City leaders will also be faced with the daunting task of trying to address a clear need for accelerated housing production at a time of a decidedly challenged city budget.

It’s common to hear long-time residents remark about how much San Mateo County cities are already changing, particularly as higher density projects have altered familiar landscapes. Though opponents may resist higher densities along transit corridors, the new buildings are helping to close the housing gap.

While there are good-sized redevelopment sites along the Peninsula, housing proposals near transit hubs often end up being whittled down to fewer units than the market demands. Redwood City, South San Francisco and Millbrae have upzoned areas around transit hubs, allowing taller buildings to be built in these areas. But proposals like the one in San Mateo would do the opposite: They would restrict the size of new buildings, constraining cities from gaining ground on the housing shortage.

Station 1300 is a mixed-use complex developed by Greenheart Land Company that is under construction in Menlo Park. The complex will include restaurants, shops, offices and 183 rental apartments on 6.5 acres, all near public transit.

The developer originally wanted to build a taller structure, with a lot more apartments. But local opposition stripped the building down to just four stories.

Opponents also organized a ballot initiative, Measure M, that sought to downzone the Downtown Plan to block construction of Station 1300 and other new developments, including Stanford University’s Middle Plaza mixed-use project on El Camino Real. Voters rejected Measure M. The ultimate cost of the fight shows up in higher prices that consumers ultimately pay.

Further north, in Brisbane, a developer wants to build 4,400 new homes and 7 million feet of new commercial space on a former railyard and landfill along the Caltrain tracks in a development called Brisbane Baylands.

Brisbane residents, who have expressed mixed feelings about the plan, are set to vote in November on a ballot initiative that would amend the city’s general plan and allow for up to 2,200 homes to be built at the site.

If voters reject the proposal, the developer, Universal Paragon Corporation, may have other options, including invoking a recent state law that allows developers to maneuver around restrictive local policies if half of their housing development is affordable.

Senate Bill 35, passed last year, streamlines the permitting process for proposed housing developments in most California cities that include at least 10 percent affordable housing.

The bill’s author, State Sen. Scott Weiner (D-San Francisco), is now pushing a second piece of legislation that would overhaul the state’s process for setting housing goals in each city.

“To reduce housing costs and end the displacement happening throughout our state, we need systemic changes in how we plan for and build housing in California,” Sen. Wiener said recently. “Too often, some cities manipulate our current laws to reduce their housing obligations to avoid building badly needed new housing, including affordable housing. Creating a more equitable process for setting housing goals ensures that all cities plan for and build the housing we need.”

Back in Redwood City, meanwhile, the decision by veteran Councilman Jeff Gee not to seek re-election means there will now be at least two new faces on the council. (John Seybert also chose not to seek re-election, and Vice Mayor Diane Howard is the sole incumbent who is running.) Both Gee and Seybert had faced criticism from people unhappy with the pace and nature of change in Redwood City, and Gee was targeted over his pro-growth votes.

Incumbents may be bowing out but growth — and all the benefits that come with it — are here to stay. Along with the challenges.