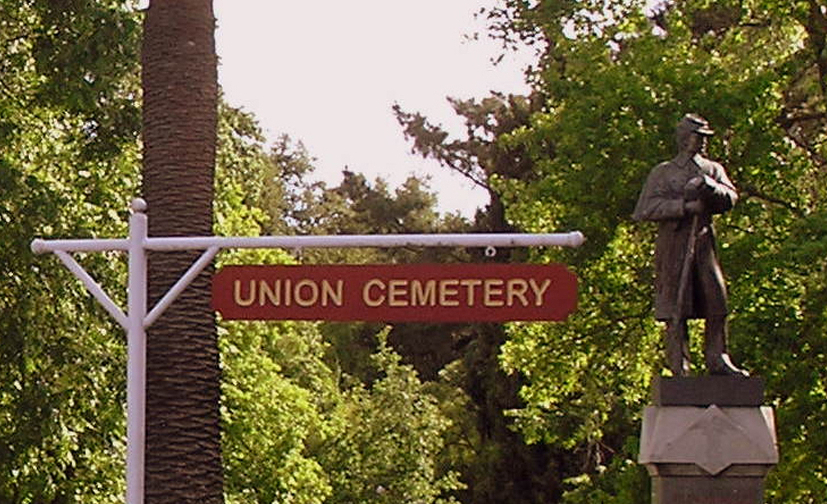

Union Cemetery in Redwood City is an urban oasis of contemplation and consideration for those from our community who died in service go our country, dating back to the Civil War.

Each Memorial Day, the Historic Union Cemetery Association conducts a ceremony to honor those who have fallen on our behalf.

This year, was no exception and so, on Monday, about 200 people gathered at Union Cemetery to hear patriotic songs, a poem and to stand together to in remembrance. What made the event of particular gravity for me was that I was asked to deliver the keynote address. It was a chance to dig into some of the issues that have dominated my life and, I believe, the life of a generation. The speech seemed to be well received, so I provide it to you here.

MEMORIAL DAY REMARKS: Thank you for the distinct honor of speaking to you today and to be part of this day in which we memorialize those who gave, as Lincoln said, the “last full measure of devotion” in service to our nation.

I have significant doubts about my qualifications to speak to you today, having never served.

Who am I to be speaking on behalf of those who died for my right to speak – to hold our nation together, to end slavery, to save the world from enslavement?

Indeed, not only did I not serve, but I actively sought to be excluded from military service.

We are all a product of our times and my time was dominated by the Vietnam War.

My brother Rick served there, stationed at Da Nang air base where, apparently, he flew radio spy missions over China. His best friend, Mark Sprague, rather than serve in Vietnam, left the country for Canada, and never came back.

There were demonstrations and marches. My Skyline Community College newspaper shared a print shop with the Black Panthers.

These were the times.

By the time I came of draft age in 1969, I had to face some difficult, sobering questions.

Should I serve? Should I fight? Should I find a way out?

What would it say about me as a principled human being if I avoided service, while others, often those without means, were doing the dirty work of fighting and dying?

In reality, I didn’t want to kill anyone. And I certainly didn’t want anyone to be shooting at me.

It was an uncomfortable time.

The war was wrong – misguided, dishonest, misled and unfair – and I developed an abiding sense that all war is wrong. I became, and remain to this day, a pacifist.

I decided I would refuse to serve.

I let my student deferment lapse. In a moment of significant anguish for my parents, I was prepared to go to prison rather than be drafted.

Then came the draft lottery.

I vividly recall sitting in my backyard with my best friend, Ed Sessler, listening on the radio while in Washington they pulled ping pong balls out of a basket.

My number came up – 278. At the time, they were drafting no higher than up to 60.

In an instant, the entire moral and practical dilemma passed.

I stayed in school. I studied journalism. I spent countless hours covering antiwar protests and marches – never as a participant, always as an observer.

But over the years, I pondered: What do I say to those who did serve? Did I stand aside and let them do the dirty work for me? Am I no different than those who paid their way out of the Civil War?

Well, I found some answers to these difficult questions.

I am a storyteller by nature and profession, so let me tell a few stories.

In 1982 – an incredible 36 years ago – I was in Washington, D.C., on Veteran’s Day – the day they had chosen to dedicate the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

As part of the day, there was a long parade and prominently featured in it was a group of Vietnam Vets from the Menlo Park Veterans Hospital suffering from PTSD before we even knew what it was. They were in-patients at the hospital and as part of their therapy, they had formed a chorus. They were on a truck bed in the parade, singing at the top of their lungs.

I met up with them, interviewed them and got to know some of them, including an Army captain who had commanded an armored unit.

The day after the parade, the Menlo Park vets gathered together and went as brothers in arms to the memorial.

I walked toward the memorial with the captain. He began to tell me his story.

His unit had been overrun, they had abandoned their vehicles and they were running for cover.

There were five of them. First one was hit, and the four of them were carrying their wounded buddy to safety. Then another was hit and three of them were carrying the two wounded. Then another was hit and then another.

In the end, all five were hit. Wounded himself, the captain dragged each of his comrades to safety. He won the purple heart and the silver star. The others died.

At the memorial, the names are grouped chronologically in the order of the reports of their deaths.

As the captain arrived at the memorial, he saw the names of the other four, in order, one after the other. He grabbed me, buried his face on my shoulder and sobbed.

Later that day, as a group, they stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and sang America the Beautiful.

Five years later, I had befriended B.T. Collins, the former Green Beret who became the first head of the California Conservation Corps, was Gov. Jerry Brown’s chief of staff, served in the state Assembly and lost a leg and an arm in Vietnam when he fumbled a live grenade.

He was a larger than life character with a hook on his right arm he liked to extend to you when you first met him. He used to describe himself as six feet two on the left and three feet four on the right.

His Assembly office door featured a poster from the move Hook.

He also was a prime mover in the funding, design and creation of the California Vietnam Veterans memorial, dedicated to the more than 5,800 Californians who died in Vietnam. It’s a wonderful memorial and if you haven’t seen it, I urge you to do so.

There, the names are organized by hometown and I decided to write a series of stories about the young men from the Peninsula who are listed there.

So, there I was in the living room of an East Palo Alto mother, talking to her about the loss of her son, a twin.

She said the loss never goes away. Sometimes, she said, when the front door opens, “I look up and expect to see him walk in.”

Just then, the front door opened, and her other son, the lone remaining twin, walked in. Both of us began to cry.

My generation still talks about the lessons of Vietnam, a loaded phrase that can mean widely varying things to different people.

Here’s the lesson I learned from Vietnam, from these forever-young Peninsula men, from their grieving families and their stories.

They went to war for different reasons.

Some of them had no other prospects – they couldn’t stay in school or didn’t want to.

Some thought it would be a way to change their lives. Some went out of duty and some just let themselves get drafted.

But they all served. They all went.

And they went, often, for the finest of reasons – out of duty, out of love of country, out of a desire to be of service to our nation and its ideals. And they fought and died, as soldiers always do, for their brothers in arms, for those at their side.

And this is what, ultimately, I learned and what gives me some solace as I try to reconcile their experiences with my own.

I can oppose war and still honor those who are willing to put their lives at risk to fight.

I honor their desire and their willingness to serve.

I honor their love of country and their willingness, no matter how reluctant, to do their duty.

And I believe the best way for us to honor them is to value their willingness to serve, to not squander this dedication and devotion.

That if we send our young people to fight and die for us, that we do so with honesty, with clarity of moral purpose and in the name of the finest of our values – freedom.

It has been my distinct honor to be with you here, on this day. Thank you.

Contact Mark Simon at mark@climaterwc.com.

*The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Climate Online.