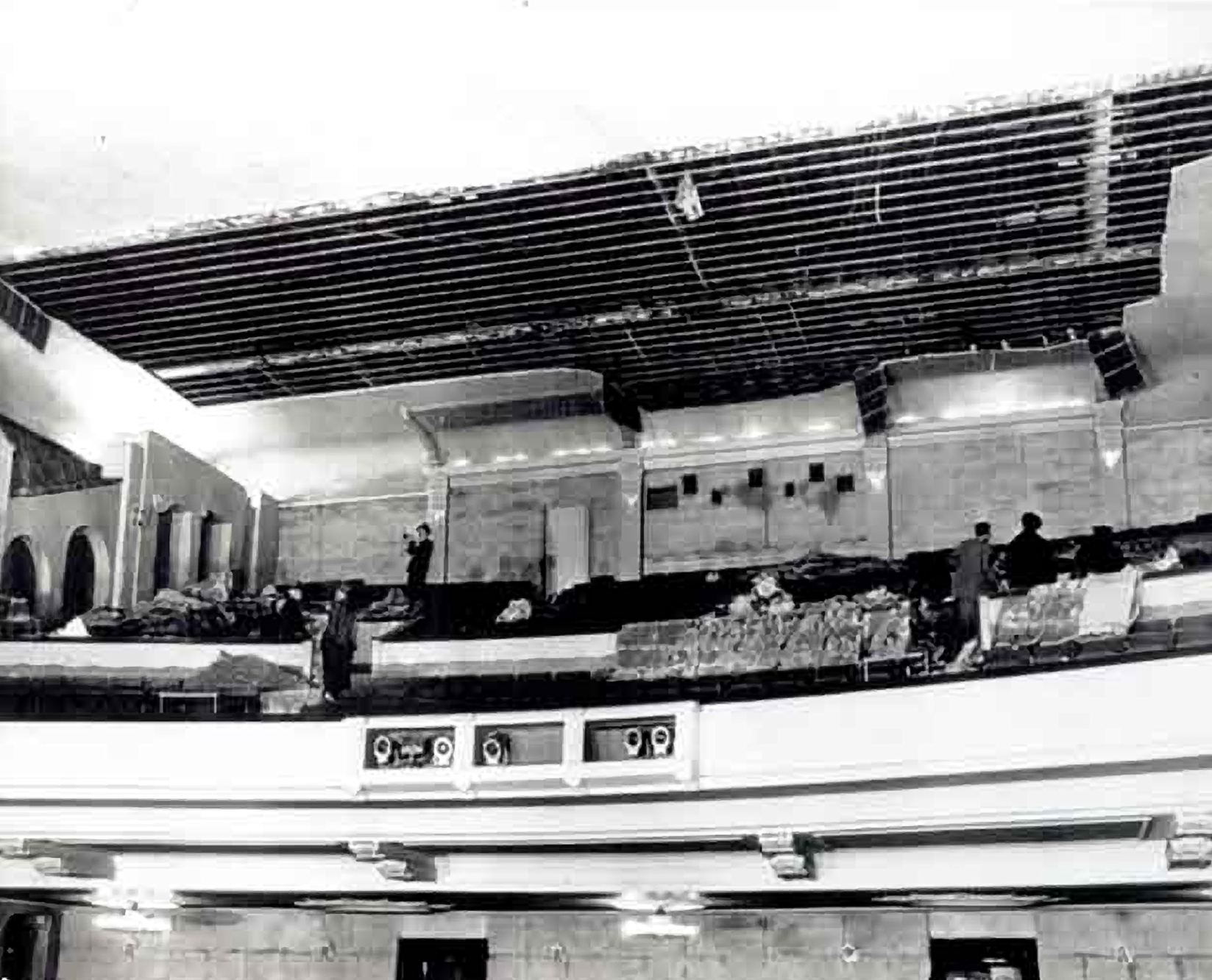

In 1950, the balcony ceiling collapsed at the Sequoia Theatre in Redwood City, injuring 27 people. After a long hiatus, the building reopened with a new interior and a new name – the Fox.

Without warning, at 11:30 p.m. on June 21, plaster fell on patrons watching The Gunfighter, a western starring Gregory Peck. The most seriously injured was a woman named Evelin Case, who suffered a skull fracture when she either jumped or fell to the main floor, according to a 2005 article in the Archives News, published by the history room at the Redwood City Library. Most of the injuries were minor wounds to the head, chest, back, arms or legs. Case was released from the hospital after a two-day stay. Fourteen lawsuits were filed, but only four were awarded judgments. The others were dismissed.

Investigators concluded that nails, which were about an inch short of what they should have been, were loosened by vibrations of trains that had passed nearby for decades. The cave-in closed the theater for three months.

Adding a touch of irony, the Sequoia was famous for the starry night experience it offered the audience. A machine projected moving clouds and twinkling skies across the ceiling, giving customers the feeling that stars were gazing down on them. That part of the ceiling was covered up during the restoration; to see what little is left, it is necessary to climb ladders and walk across catwalks.

The 1929 opening of the Sequoia, which replaced the original and much smaller Sequoia cinema located nearby, was big news. The Redwood City Tribune reported every detail, including a 10-paragraph story on the show house organ alone. Patrons imagine “they are in a street in a town somewhere in Spain,” the paper said in reporting on the 1,200-seat theater’s Moorish interior.

The walls consisted of a series of archways that indeed resembled a courtyard in old Spain. An estimated 3,000 people attended the debut on January 5 to see “Three Week-Ends,” starring Clara Bow. The theater also had a stage and dressing rooms for vaudeville acts. In addition to viewing the movie, the opening night throng was entertained by a band as well as dancers.

The opening was “a big event in town,” Louie Dematteis, an usher who went on to become San Mateo County District Attorney, recalled in an interview in the 1990s. “They had searchlights. It was like a night at the opera in San Francisco.” He added that some of the vaudeville acts were “terrible.”

Reopening Night

The reopening on September 15, 1950, came after extensive remodeling by designer Carl Moeller, whose style was described as “Art Moderne meets Streamlined.” The marquee, terrazzo tile in the foyer, a mirrored entrance and ornate gold leaf combined to form a near-classic example of 1950s Art Deco. Even though Moeller covered up or replaced much of the interior, the lobby, with arches that line the walls, still has the feel of the original.

More than 2,000 people turned out to see the renovated theater, which was described as “completely remodeled and shining from a giant-sized portion of gold paint.” The film offering was “My Blue Heaven,” starring Betty Grable. There was plenty of entertainment outside, a warmup for the first showing since the ceiling had come down. Crowds began gathering in front of the Fox more than an hour before the outdoor festivities. Temporary bleachers were packed as the throng watched dancers, heard singers and was introduced to visiting celebrities. The big names included actors George Jessel, Howard Keel and Roddy McDowell.

The show was a benefit for the Korean War effort, and customers had to buy a bond to get in. Patrons entered under a marquee that assured them “Movies are Better Than Ever,” a slogan Hollywood hoped would wean viewers off the new medium of television.

The advent of TV wasn’t the only reason the original Sequoia was a tough act to follow. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1948 led to the breakup of big movie house chains. Many movie palaces built in the same era went under, but the Fox survived.

Why? There’s probably no one reason, but in 1995 a survey found that 96 percent of those interviewed felt the Fox should become a “social and cultural hub.” Today it anchors one end of Courthouse Square, known to many as “Redwood City’s living room.” Maybe movies and television can coexist after all.