Fifty some years ago, Rafael Garcia made the journey from Mexico to Redwood City to grab hold of the American dream. Over the decades, generations of émigrés from his village of Aguililla in the state of Michoacán have made the same migration to Redwood City, many of them settling in the North Fair Oaks neighborhood. Like them, Garcia arrived eager to work — in car washes, in kitchens — whatever it took to secure a rung on that fabled ladder of success.

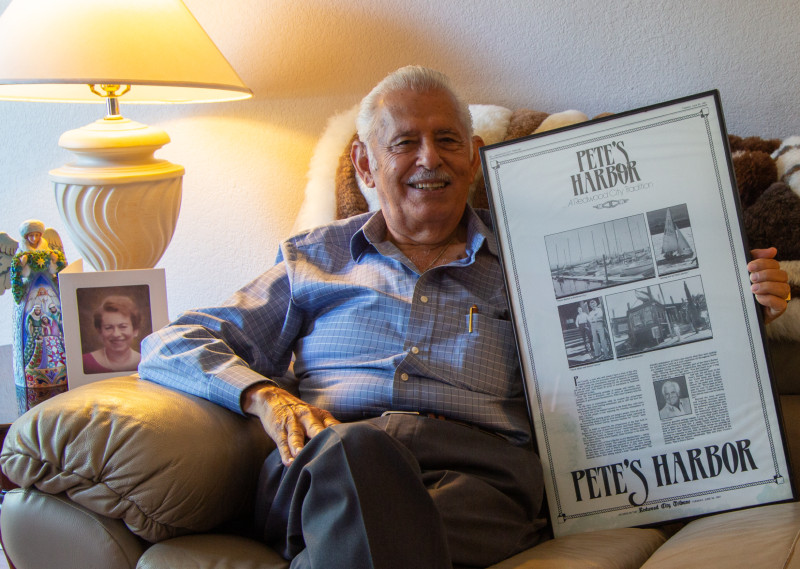

He made it. Today, age 78 and comfortably retired, Garcia can look back on a life of remarkable achievement, especially for someone who had had to quit school after the third grade to work fulltime on his dad’s farm. An unwavering work ethic and an ability to listen were crucial. But Garcia also got a lucky break, when Pete Uccelli, owner of Pete’s Harbor, spotted him and mentored the young immigrant. Uccelli eventually made Garcia a partner in his waterfront restaurant, where they worked side by side serving good food – with a side of hospitality.

“I have been very fortunate in my life overall,” Garcia said, “but meeting Pete Uccelli was a gift from God.”

His opportunity to go to work with Uccelli was all the result of a chance encounter in 1972, when Garcia was working at one of his restaurant jobs, busing tables at Scotty Campbell’s in Atherton. The harbor owner would often come in for dinner.

“Pete saw something in Rafael that he thought amazing,” Paula Uccelli, Pete Uccelli’s widow, recalled. He asked the personable, hustling busboy to come work for him at Pete’s Harbor and run what at the time was a small hamburger shack at the marina. “That was a big decision for me to make,” said Garcia. “It was a little place and I had to quit my job at Stickney’s Restaurant to work there.”

Ordained the cook, Garcia protested, “But I don’t know how to cook.” To which Uccelli replied, “Me either. Let’s learn it together.”

This challenge left Garcia unfazed. “I was always willing to learn and wasn’t afraid to ask questions. When I came to the United States, I learned English one word at a time and was never afraid to be wrong. All of the trade abilities I have picked up I learned by doing them.”

The youngest of 12 children, Garcia learned the value of hard labor, working fulltime on his father’s farm. But he dreamed of opportunities found in the United States of America. With a cousin already established in Palo Alto, Garcia, then 20, traveled to Mexico City and applied for a passport and visa. It took a year but he secured the proper documents and in 1964 made his first trip to the promised land.

Working Two Jobs

Garcia lived with his cousin and got his first job at a carwash, earning $1.50 per hour. Before long he added a second job, bicycling between them and working 14 hours or more a day. The determination to earn and save came with a purpose: to return home and marry the girl he left behind.

There was a Sunday night mating ritual in Aguilillia’s town plaza. The girls would form a ring and move clockwise. The boys made an inner circle, walking counterclockwise, carrying a flower. If a fellow spotted the girl of his fancy he would offer her the flower. Acceptance indicated a mutual attraction. The promise of romance.

“But sometimes they said no,” Garcia said, “and you had to go around again and give it another try.” Some girls would keep their would-be suitor spinning for several laps before accepting the offering. The apple of Garcia’s eye, a young beauty by the name of Carolina, took the flower on the second pass. To further solidify the union, she gave him a flower as well, signifying the intent for a relationship.

After 10 months in Palo Alto, he’d saved enough to marry Carolina and bring her with him to start a life together in a rented apartment. He continued working back-to-back shifts at restaurants for the next four years, all the while keeping a sharp eye out for a better opportunity.

In addition to Scotty Campbell’s and Stickney’s, Garcia also worked in the Stanford Hospital kitchen and had studied what chefs did. When he came to work for Uccelli, the first menu contribution he cobbled together was a Thousand Island dressing (onions being the key ingredient) applied to the burgers. The shack wasn’t serving more than 16 people a day and Garcia worried how Uccelli was going to pay him based on such a small clientele. “I was thinking I had made a mistake going to work for Pete.”

Customers liked the burgers. Then Garcia added a weekly “Mexican night” special to change things up. Business at the shack suddenly began to pick up — so much so that Garcia had to hire more cooks. He and Uccelli were struggling to keep up, Garcia recalled. “That’s when Pete decided to build the restaurant.” Located at the end of Smith Slough and Redwood Creek, the Harbor House restaurant opened in 1973 and for decades was a popular community haunt.

Family Responsibilities

Meanwhile, Garcia’s responsibilities were growing at work and home. By then, he and Carolina had two children: Caroline and Bobby, with a third child, Laticia born that same year. By 1975 the family would round out with a fourth child, Jaime. Still, after working in the kitchen from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m., Garcia would hang up his apron, pick up a hammer and help Uccelli add onto the Harbor House.

“My father was always busy working,” said daughter Caroline Gomez. “He worked from 7 a.m. till 11 p.m., so we didn’t really see him until Sunday, which was family day. Then we would drive up to the mountain, beach or park, have lunch and play. Sunday was an important day for us because he worked all the time.”

One day Pete Uccelli turned to Garcia and said, “You’re the one making this business grow, how about becoming a partner?”

Over the years other partners would come and go: restauranteur Leo Giorgetti; Mario Biagi, a Redwood City mayor; Chuck Major, formerly with the city’s police department; and nephew Scott Uccelli. But Garcia was a constant at the Harbor House for 26 years.

Though he felt best-suited for overseeing the kitchen staff and planning the menus, Uccelli wanted Garcia engaging the customers. “Look, Rafael, you need to be in the front so you can see what is going on,” he said.

“Rafael was congenial as hell and easy to talk to. Just like Pete. From the first time I met him I could tell he was a go-getter,” said John Copeland, an old friend and longtime Harbor House customer.

Uccelli also mentored Garcia in money matters. “He was always telling me to invest in some kind of property,” Garcia said. “He saw my growing family.”

Money Talks

“One time we went with him to Mexico to look at property,” said Paula Uccelli. “He had to open an account at the bank and asked Pete, ‘Can you come with me to the bank to make sure I open the right account?’ Pete asked him if he had a relationship with this particular bank, to which Rafael said, yes, that the tellers even called him by his first name. Pete told him, ‘After you make this deposit they will be calling you Mr. Garcia.’ And that’s exactly what happened.”

Garcia owns a home in Mexico and recently sold his 150-acre farm and ranch there. With contractor friend Danny Wong, he also purchased a condemned historic building in Morgan Hill. Together they renovated the structure, which today provides Garcia with retirement income.

Once Paula Uccelli got angry with Garcia at his daughter’s graduation. “Laticia was on stage receiving her diploma with honors from Santa Clara University,” she said. “Rafael turns to Carolina and says how amazing it was that their daughter could be so smart coming from two stupid Mexicans. That’s when I said, ‘You may not have a formal education, Rafael, but you are not stupid!’ Rafael is so good at listening. He took every opportunity to learn from others and he’s incredibly smart. I wasn’t going to let him get away with that comment.”

After retiring from the Harbor House in 1998, Garcia finally found time to travel with Carolina. Pete Uccelli died in 2005, and the Harbor House closed its doors in 2011. Today the Blu Harbor apartment complex occupies the site where the restaurant and marina used to be.

Carolina Garcia died in 2016, and after 52 years of marriage Rafael struggles to fill the void. “My mom was everything to my father,” Caroline Gomez said. “He misses her — he’s just not the same without her.” That said, she added, he is hardly idle in retirement, and always has a project to work on.

A U.S. citizen since 2003, Garcia can reflect with gratitude on being able to come to America with nothing and “make something of myself. I never took that for granted.” The majority of would-be immigrants today, he believes, “are simply trying to make a better life for themselves. This great country was built on the backs of people like me: hard-working Mexican, Irish, Italian or whoever. So, I don’t understand those who say they don’t want us here … But I always got along great with the customers at the Harbor House. They never treated me badly.