By Elizabeth Sloan

Remember the day the sky turned orange? Across the Bay Area Sept. 9, the sun disappeared, temperatures dropped, and it got dark—really dark. Streetlights came on at midday. The world took on a burnt orange hue. It was strange and unsettling, and on top of a global pandemic, economic fallout, social unrest, political division, and raging wildfires, it made some people wonder: What next? Locusts? Raining frogs?

Anybody with a smartphone and a couple of minutes could figure out the culprit. Particulate matter from the California wildfires, snuggling down on top of a layer of marine air, can turn normal sunlight into apocalyptic orange skies. But what if that explanation hadn’t been readily available and people were left to their own dark imaginations about the end of the world?

That’s what happened in 536 A.D., when an inexplicable, choking fog blotted out the sun, plunging Europe, Asia and the Middle East into 24-hour darkness—for two years. Crops failed, famine spread, and then—after extended cold and starvation—bubonic plague followed. This one-two punch, climatic and pathological, wiped out 100 million people. Only recently did scientists determine the likely cause: an Icelandic volcano that spewed tons of ash into the sky.

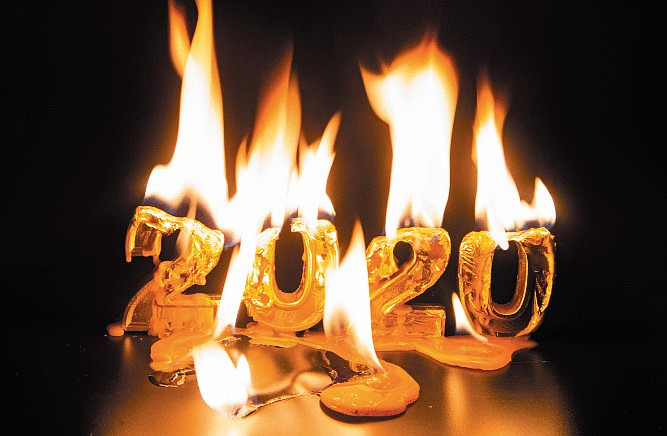

Putting 2020 in Perspective

2020 has been an extraordinary year, to be sure. Nobody is trivializing the impacts: lives and livelihoods lost. Food and shelter insecurity. Upended patterns of working and learning. Zoom fatigue. Life milestones canceled or deferred. Social isolation and loneliness.

But is it the worst year ever?

Objectively, globally; probably not. Most historians give that undesirable distinction to the year of the Icelandic volcano. But there are other contenders closer to home. Many Americans of a certain age remember 1968 fondly—the Summer of Love, the moon race, the civil rights movement. But 1968 had Vietnam, rage and protest filling the streets, shocking assassinations. For anxiety and social upheaval, it rivals 2020.

As devastating as Covid-19 already is (more than 1.3 million deaths globally by mid-November), other pandemics will exceed it. The Black Death (bubonic plague) took 200 million lives in the 1300s. Spanish Flu (erroneously named—it didn’t start anywhere near Spain) killed an estimated 50 million people from 1918 to 1920. Almost no family escaped those scourges. And in those pre-modern medicine, pre-information ages, nobody understood them either.

If 2020 is not the worst year in history, why are so many calling it that? For starters, this year has been plenty bad. But there are also social, emotional, and biological forces at play in how humans interpret the events of their lives.

“When you talk about assaults on lives, these things are real,” says Stanford psychiatrist Dr. Mickey Trockel. “This is the worst year in many people’s own experience, in their personal recollection. (They think) ‘It certainly feels bad to me.’”

Beyond personal perspective, evolutionary biology plays a part.

“We are wired to be vigilant,” says Trockel, “and that works re-ally well when we are facing a threat that is real and immediate. We are poorly adapted to an environment where we are constantly bombarded by false threats, or exaggerated threats. That’s just a recipe for anxiety.”

So, being chased by a saber tooth tiger? Real, immediate threat. The possibility of getting Covid, or losing a job, or watching kids fall behind in their learning? Definitely real, but not as immediate. Even unrealized dangers, though, can unleash a flow of stress hormones to fuel a physical reaction like fight or a flight.

A World Upside Down

For insults to normalcy, 2020 has been unusual for its sheer number of challenges, their simultaneity, and how quickly they transformed everything. For Mike Callagy, the day of transformation was March 3.

“The year started with such high hopes,” says Callagy who as San Mateo County manager leads a staff of 5,500 and a $3.7 billion organization providing safety net services, health, parks, public works and public safety programs for 760,000 residents. “The budget was outstanding. We had a thriving economy. We had plans to do so many great things.”

Then came the county’s first confirmed case of Covid.

“We needed to shut things down immediately, open the Emergency Operations Center, and respond to so many things—all without a real blueprint,” he says. “You can rely on your emergency training, your instincts. But until you have been through it, you cannot begin to understand the complexities.”

Securing supplies of personal protective equipment for the county kept Callagy up at night.

“We knew what it meant for the health and safety of our frontline workers,” he says. “Our people were on the phones day and night, calling all over the world—only to hear: ‘Sorry, you got out bid.’ Or,’ We can get it to you in four months.’ It was crazy.”

Shortages eventually eased, helped in part by donations from local companies. The county and its public health officer, Dr. Scott Morrow, have been praised for their response but Callagy says everyone involved deserves credit.

“I am so proud of how everybody came together—our employees, our elected officials, our health people–and our residents. We had 1,500 volunteers who signed up to do anything we needed.”

While the crises have been brutal, says Callagy, invaluable lessons could not have come without them.

Unexpected Changes

For Dr. Elina Hudson, a physician with the Palo Alto Veteran’s Administration Medical Center and mother of three school-aged boys, the transformation took a few weeks, but was just as dramatic. Speaking with medical colleagues around the world in early March, Hudson was not alarmed.

“We learned about this virus in medical school 25 years ago,” she says. “It was not considered a big danger. ‘How bad can it be?’ we were asking each other.”

Soon they had their answer.

“We started watching New York,” she says, “the pictures of overwhelmed medical people, the morgue trucks lined up outside the hospitals.”

The VA completely transformed its operations, pooling resources and creating response teams—waiting for the surge they all assumed was on its way. Hudson worked in the urgent care and Covid clinics, treating patients, attending endless meetings. “We were ready to be overwhelmed,” Hudson recalls. “There was a lot of anxiety.”

The surge never came, though case numbers have recently been on the rise. Hudson says as she treated patients, “I got to know more about how this disease worked, how it progressed, who was at risk, who would likely do well and who wouldn’t.”

Trockel, who specializes in physician wellness, says people have also experienced a psychological impact this year from feeling that they were accomplishing less.

“It’s important to think about how we see ourselves,” he says. “Early on, when everybody was transitioning to remote working and being alone at home, the change in venue meant a loss of efficiency. It feels harder to get same amount done. And it’s easy to get down on yourself.”

Stress with Doing Less

Hudson saw the same thing in her practice.

“There are so many Type A people here, and they are all going 150 miles an hour,” she says. “Along with the isolation, being less productive makes people very stressed.”

Her own household hasn’t been immune, although her husband Greg Hudson was already managing shopping, meals and childcare when the pandemic hit. But their high-energy boys were used to going to school, being with friends, playing soccer, and doing lots of physical activity outside. Remote learning did not work well and by June, “They seemed drained of energy, fatigued,” she says. “Almost like a sub-depression. It was alarming.”

After a chance encounter with a dog owner at a park, Hudson told her husband: “Okay, it’s time for either a shrink or a puppy.” Three days later, an exuberant German Shepard joined the household.

“It made all the difference,” she says.

Psychological wellbeing is affected by the news, and how people consume it.

“Social media expose people to information individually tailored for them,” Trockel, the Stanford psychiatrist, observes. “It’s a simple business practice—selecting items they think will interest you specifically, in order to sell you more stuff.”

The selection, he says, skews negative, for neuroscientific reasons.

“It’s no secret that YouTube videos that are most disseminated and most watched are the negative ones. Bad news is viewed more extensively. It’s more grip-ping. We watch it all the way through. It renders more value for advertisers.”

The Economy

It’s a little early to predict Covid’s eventual toll on the Bay Area economy. Suffice it to say: 2020 was very tough on local businesses.

In January, Angelica’s in downtown Redwood City seemed poised for a different kind of surge.

“We had events booked out through the year—many of them sold out,” says Angelica Cuschieri, who co-owns the restaurant with husband Peter Cuschieri. “We’d have 200 people here on a weekend.”

When the restaurant had to close in late March, the federal stimulus loan helped keep things going. The couple partially reopened in late May, but the takeout style that was allowed at the time didn’t fit their operation well. Aside from indoor dining, “we were mostly about business catering and events,” Peter Cuschieri says. “All that was gone.”

Street protests and smoky skies kept customers away, and costs for everything—food, gloves, masks, special sanitizing equipment–all got higher while revenues shrank.

The Cuschieris’ normal recipe for success built around the food, service, ambiance and live entertainment needed a new ingredient in the Covid era: customer confidence that an evening at Angelica’s was safe. Now restaurant staff sanitizes like fiends and is strict about distancing and masks. The menu has been reimagined to bring in younger people (who are more likely to go out to eat now) and Angelica’s outdoor spaces have been a plus.

The couple also credits their landlords and Redwood City for helping them survive.

“It is teamwork and tenacity that keep us going,” Peter Cuschieri says.

Three of the couple’s eight children work in the restaurant while attending college: Krystal is general manager, Angel runs the bar, and Mary Elena handles front-of-house duties.

“We are optimistic about the future,” says Angelica Cuschieri, though she wonders how things will do during winter weather. “I think it will be May before things start to turn around.”

Economic recovery—for individual owners and the region at large—remains a daunting challenge as the year closes.

“We talk about this all the time,” says County Manager Callagy. “We created the Covid Compliance Team to work with businesses, offering carrots rather than sticks. But this is a deadly disease. We cannot fill restaurants and stores. We have to do it in a strategic way. Wearing masks is critical. Everyone will have to sacrifice to save lives.”

Look for the Up Side

In the midst of the storm, are there silver linings? Absolutely, say Bay Area residents.

Many report a sense of solidarity, of “being in this together.” People shared coping strategies, created social pods, swapped recipes and TV recommendations, traded everything from childcare to haircuts. Sheltering in place brought a return to hearth and home. Families spent more time together. Previously unaquainted neighbors got to know each other on the endless walks everyone seemed to be taking. People got creative and developed new hobbies. Others reported a sense of relief that life got less busy.

On the plus side, Hudson was freed from juggling three sets of soccer schedules for her kids. She wonders if post-pandemic, the go-go Silicon Valley could retain its newfound sense of time and space. Her family, from the former Soviet Union, was deeply imprinted with the ravages and deprivations of World War II.

“Maybe this experience could bring Americans a little more patience and gratitude,” Hudson says.

Faced with the prospect of canceling milestones and celebrations, people had to come up with “Plan B’s.” Weddings that could no longer be held in a church had to downsize, becoming more intimate with less emphasis on “the party.”

Zoom calls sprouted among families and friends who never talked. Video chat became a new venue for weddings, bar mitzvahs, funerals, graduations and live performances, rendering geography irrelevant and often producing, for some, a surprising verdict: That was so much better than I expected!

Telemedicine is also on the rise; even online psychological counseling seems to have advantages—lowering barriers of access for people seeking help.

Will the changes of 2020 last? Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom says working from home will continue to grow, with caveats. Not everybody can work from home, which could generate economic inequality. For it to work well, people have to choose it. A hybrid seems best, with at least some days in the office.

Stanford historian Walter Sheidel has studied how past pandemics have changed societies. The Black Death, he says, led to collective bargaining and weakened feudalism. But a pandemic has to be so big, so painful, that change becomes the only alternative. For all its destruction, it’s not clear yet if Covid-19 rises to that world-changing, history-altering level.

Gratitude and Compassion

What will not change is the need for human resilience, which can be cultivated, according to Trockel.

“There are two qualities that resilient people seem to have: Gratitude and compassion. If you have the capacity to notice and appreciate what is good in your life, there are demonstrable mental health benefits … When we start with empathy for others, we cultivate better brain chemistry in ourselves. Engaging with others with an intention to help—to alleviate their suffering–activates a set of neural pathways that trigger pleasure centers in our own brains.”

Short of cultivating these qualities—an ongoing project, surely—what can people do to cope with a year which, if not the worst ever, is still plenty challenging?

Trockel points to the list of recommendations published by the California Surgeon General for keeping stress in check during Covid: plenty of aerobic exercise, good eating habits, consistent sleep patterns, meditative practices and social support.

And one last RX, he adds: “Go on a media diet. Turn off the devices.”