By Vlae Kershner

Everyone’s finally doing this electric car thing, right?

It’s been 31 years since the California Air Resources Board first voted to require the production of zero-emission vehicles. In those days, the main enemy was smog, while now it’s climate change due to greenhouse gases.

The regulations didn’t have many teeth until last September, when Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order requiring that all new passenger vehicles sold in the state produce zero emissions by 2035.

That mostly means plug-in electric cars, though hydrogen fuel cells qualify as well.

With its green mindset and temperate climate, Northern California has surged into the lead in EVs, with more than 327,000 registered in PG&E’s service area, about one-fifth of the national total.

San Mateo County, through the community-controlled Peninsula Clean Energy joint powers agency, has created a $28 million EV Ready Program that seeks to install 3,500 charging ports in the county over four years. “Our overall mission is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in San Mateo County. The biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the county is transportation,” said Jan Pepper, chief executive of the agency.

Pepper drives a Kia Niro. “It’s so much less expensive to operate. The fuel is way less expensive.”

Even under the 2035 regulations, Californians will be allowed to drive cars that run on fossil fuels and buy them used. That means EVs will have to satisfy consumers’ desires for the changeover to take full effect.

Barriers to Buying

According to a survey by cars.com, 66 percent of consumers in a national survey expressed a desire to buy an EV after hearing President Biden’s plan to invest $174 billion in the technology, but 81 percent saw barriers to purchase. The main ones were cost, limited range and a lack of charging stations.

The drawbacks are overstated, according to Carleen Cullen, founder and executive director of Drive Clean Bay Area, which runs weekly online seminars for potential EV buyers.

“The primary issue is consumers have not been able to keep up with the advancements. People don’t know there’s more than Tesla and the Bolt,” said Cullen, who has been driving electric for nine years and has a Chevy Bolt, Tesla Model Y and Kia Niro. Besides not pumping carbon into the air, advantages include “technology, cost, the fact that vehicles are fun to drive, being able to accelerate immediately merging into traffic. It’s kind of a no-brainer when people understand.”

So what’s keeping people from buying an EV? For many, it’s range anxiety.

Most new EVs come with a range of 250 to 300 miles. Since heat or air conditioning draws directly from the battery, it degrades range. A Car and Driver magazine test in Michigan showed a Tesla Model 3 Long Range lost over 60 miles with the seat warmers on and heat at full blast.

Consider this nightmare scenario: Driving to Tahoe in heavy winter traffic in a loaded SUV, shivering with the heat turned off to save the battery, and the range gauge (an estimate, not a precise figure) drops into the single digits.

Relief is on the way as the charging network gets built out. Maps on chargehub.com show dozens of ports in San Mateo County and along major highways. Along Interstate 80, stations are concentrated in Auburn and Truckee, with a handful at the exits on the climb in between.

Recharging on the Road

For road trips to Southern California or the Pacific Northwest, there are frequent charging stations on I-5 both north and south.

Charging comes in three levels.

Bare-bones Level 1 is sufficient for many people’s daily needs, said presenter Annika Osborn at a recent Drive Clean Bay Area online seminar. “If you are able to charge at home, the system that works is to plug into your standard 120-volt outlet,” with four to six miles per hour of charging. Since most Bay Area residents drive less than 35 miles a day, an overnight charge is sufficient.

“If you drive over 50 miles a day, you can charge at work or purchase a Level 2 charging system,” installing 240-volt outlets (like those used for home dryers) at the side of the house. This produces up to 22 to 25 miles of charge per hour, but may require upgrading the electrical system, especially in older houses. Most public charging stations are also built at Level 2.

Finally, there are Level 3 systems, also called Direct Current Fast Charging. Tesla operates its own Supercharger network, while other manufacturers use shared systems. These can add a 50 percent charge in 20 to 30 minutes, which makes them ideal for restaurant stops on road trips. Charging speeds vary depending on the battery.

Drivers will have to become accustomed to starting out with less than the equivalent of a full tank. Cathy Zoi, CEO of the charging network EVgo, told a Stanford Energy Seminar, “The difficult part in fast-charging is that the further the customer goes in charging, the lower the charge rate than results, and in fact when we go past 80 percent charging we’re effectively turning DC into something not much faster than a Level 2 charger. Fifty to 80 percent is the place where most people charge.” Charging only to 80 percent also protects the battery.

Access at Apartments

Charging at home can be tricky for apartment dwellers. University of California at Davis researchers found that 18 percent of all-electric EV owners went back to gasoline-powered vehicles, the main reason being lack of access to Level 2 charging at home.

This problem is being addressed, Pepper said. Peninsula Clean Energy provides technical assistance for apartment owners to build charging stations. In older apartments, only Level 1 charging may be possible because of the electrical limitations. For new buildings, PCE is suggesting municipalities require electricity for every parking space, including a number of Level 2 chargers depending on size.

Another big issue, costs, is headed in the direction of the EV.

Consumer Reports found that in most cases, EVs cost more upfront but save money over the lifetime of the vehicle, estimated at 200,000 miles. “For example, a Chevrolet Bolt costs $8,000 more to purchase than a Hyundai Elantra GT, but the Bolt costs $15,000

The American Automobile Association found over five years and 75,000 miles, “The overall cost of owning a new compact electric vehicle is only slightly more expensive—about $600 annually—than its gas-powered counterpart.”

The longer a vehicle is driven, the better the EV compares because of reduced maintenance and fuel costs.

New EVs are boosted by a federal rebate of up to $7,500. This is not available for Tesla or General Motors because they maxed out by selling 200,000 vehicles, but the ceiling would be raised under rebate extension legislation proposed by the Biden administration.

Finding the Incentives

Other incentives include a $1,500 state Clean Fuel Reward and reduced-interest loans for buyers with low credit. Consumers can see what incentives they are eligible for at ev.pge.com. The site also includes a comparison of ranges and costs for 71 battery electric and plug-in hybrid models.

Another benefit is a decal that allows single-occupant use of carpool lanes on Bay Area highways and bridges, with some restrictions.

Heavy incentives—including free parking and reduced road and ferry tolls—have been instrumental in making Norway the first country where more than half of all new vehicles sold are all-electric and most of the rest hybrid.

In California, EVs had about a 9 percent share of new car sales in California in the first quarter of 2021, but only account for a little over 2 percent of the 28 million vehicles on the road, Cullen said.

Nationally, battery EV is dominated by Tesla with a 70 percent market share in the first quarter, while Toyota commands the hybrid market, surprisingly led not by the pioneer 20-year-old Prius line but by the RAV4 Hybrid and Sienna.

Nearly 20 percent of those in the cars.com survey said a lack of SUVs in the current vehicle lineup was deterring them from buying. But new models are proving popular, with waiting lists for the Tesla Model Y and Ford Mustang Mach E. The Volkswagen ID.4, popular in Europe, is just coming on the market.

Behind the Wheel

A fun way to check out a variety of models is during National Drive Electric Week. Enthusiastic owners bring their vehicles and provide test drives. The shows went online only last year due to Covid-19 but are coming back, with one scheduled for Daly City on Sept. 26.

Drive Clean Bay Area partners with a car broker twice a year to offer discounts on a variety of models averaging $2,000 savings, Cullen said.

Another concern is availability of electricity. The state’s goal is to produce all its electricity carbon-free by 2045. To do that while also electrifying transportation and other sectors of the economy is expected to require nearly tripling the capacity of the electric grid.

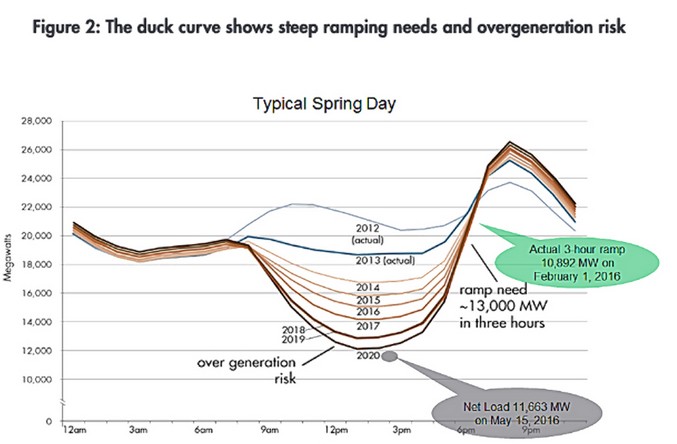

With solar production increasing rapidly, peak load on the system has moved from the afternoon into the early evening. The California Independent System Operator has labeled the phenomenon the duck curve because a graph of net electricity demand dips like the back of the waterfowl during peak solar hours before climbing like the neck as the sun sets. Twice during last August’s unusual heat wave, Stage 3 power emergencies forced outages in the 6 p.m-to-8 p.m. timeframe.

The duck curve means California generates more solar than it can use at times, especially cool spring days, requiring deliveries to be curtailed. CAISO spokeswoman Ann Gonzales said, “It’s too early to tell, but in general we recognize electric vehicles as a promising way to reduce oversupply in the middle of the day and curtailments.”

Peninsula Clean Energy is looking at adding battery storage to its 200 MW Wright Solar facility in Los Banos to capture the sunshine for evenings.

Power for Power

Further off are projects that will allow two-way power transfer. EVs would feed on cheap solar during the day, then disgorge it into the grid during the early evening, with the owners being paid. “Vehicle manufacturers aren’t there yet. I’m hopeful the day can come soon,” said PCE Director of Power Resources Siobhan Doherty.

PG&E offers special rates for EV charging at home, with overnight charging costing the equivalent of about $1.70 per gallon of gasoline. Under time-of-use rules being phased in, electricity will be most expensive from 4 p.m. to 9 p.m., especially during the summer.

Another way to shift the load is to encourage daytime charging at work. The seven-story government center parking structure under construction on Middlefield Road in downtown Redwood City is a prime example. Helped by a $248,000 grant from Peninsula Clean Energy, 124 charging ports are being installed, with pre-wiring allowing expansion to all 1,100 parking spaces if customer demand grows.

The parking center is expected to open in September. Stalls will initially be for government employees only but could be expanded to the public on evenings and weekends.

Beyond EVs, zero-emissions requirements can be met by hydrogen-powered vehicles, because fuel cells provide more energy density than batteries in a limited amount of space.

Forklifts in warehouses, where indoor air quality doesn’t allow for diesel or gas engines, have been moving from batteries to hydrogen because of faster refueling and less downtime, said Joe Powell, retired Shell chief scientist, in a Stanford talk. Those advantages could extend to other sectors.

“For trucking and heavy-duty, hydrogen is more cost-effective,” Powell said. In addition, “hydrogen storage makes sense for truck stops,” because it would be difficult to store enough electricity to overcome power outages and periods of low solar and wind.

Toyota already has a hydrogen car on the market, the Mirai, with range up to 402 miles. But fuel costs are higher than for battery EVs, and there are few hydrogen stations.

Most hydrogen today is produced either by reforming natural gas molecules or by electrolysis. Under the state’s Senate Bill 100 goals, 65 percent of retail electricity is supposed to be generated from renewable and non-carbon sources by 2030 and all of it by 2045.

“If you use excess solar for hydrolysis conversion, then you have hydrogen that’s totally renewable, no greenhouse gases,” Pepper said. “If you’re using natural gas to produce hydrogen, that’s not really moving in the right direction.”