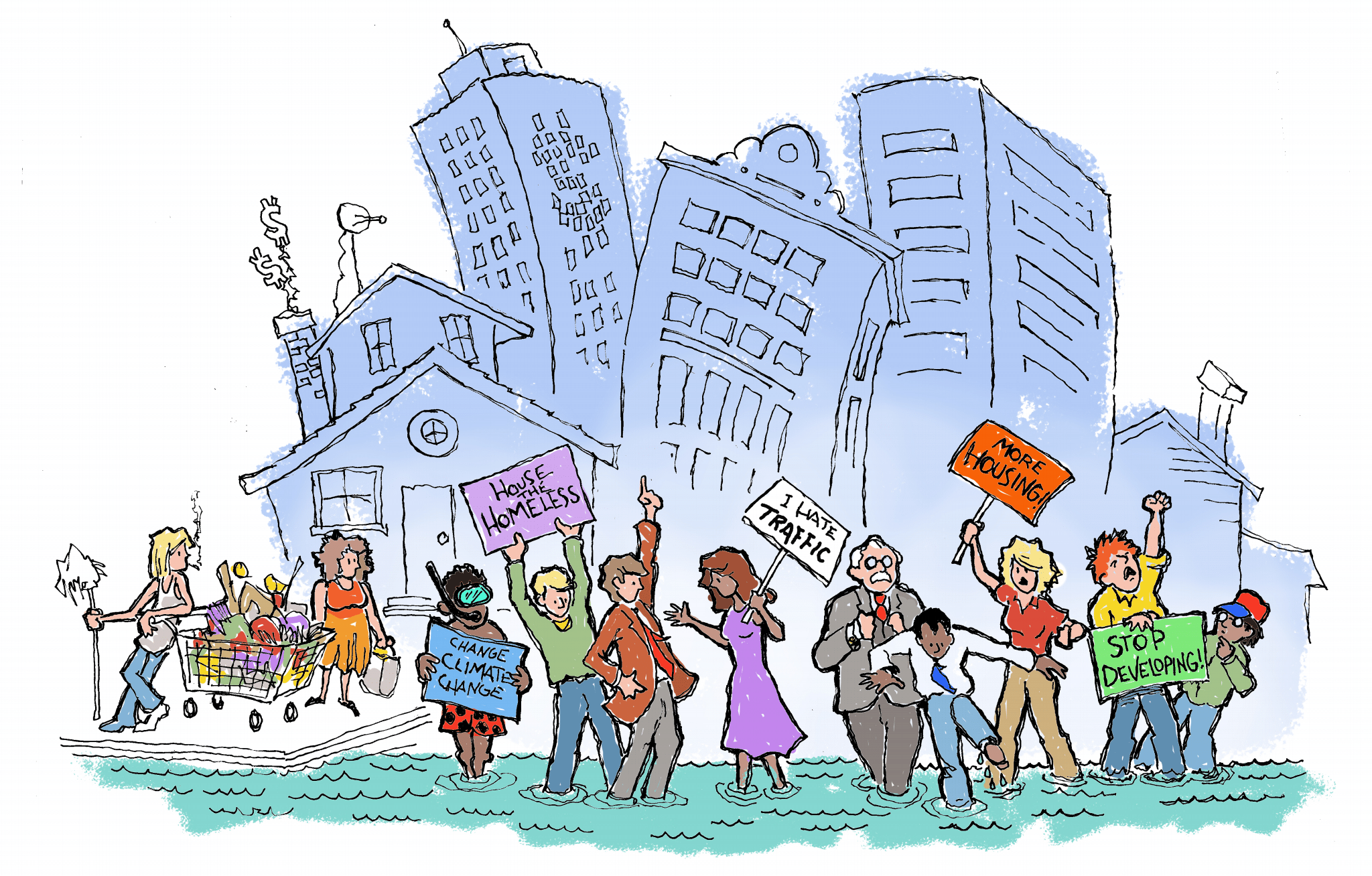

If any single Peninsula community is ground zero for the tensions that come with change, it’s Redwood City. The building boom of a decade ago transformed the town into a central gathering place for the region and shook off the mantle of suburbanism that prompted many to think of the Peninsula as a “hotbed of social rest.” But the transformative boom has caused significant alarm among many residents, precisely because it was transformative. They objected that the changes in Redwood City came at the cost of the community’s fundamental character. It was—still is—common to hear some people lament that they miss the Redwood City of 20 or 30 years ago.

Meanwhile, people on either side of Redwood City—in Menlo Park and San Carlos—frequently recoiled at the seeming explosion of high-rise, high-density commercial and residential development, centered, but not limited to, the city’s downtown core. It often is said in those other communities that “we would never do what Redwood City did.”

While this debate was evolving, a housing crisis unfolded and has proven just as much of a threat to the character of these local communities as any building boom. Similar battle lines were drawn between those who wanted to guard against a community’s becoming an enclave solely for the wealthy and those who wanted to preserve the suburban character that drew them here.

But the 2022 local election cycle may be the year when a middle ground has emerged.

With changing demographics, increasingly unforgiving state mandates and the growth of district elections, this year’s crop of candidates—new and returning—seems prepared to accept that more housing must be built, while still asserting that it can be done in a manner that retains the atmosphere many residents find fundamental.

With changing demographics, increasingly unforgiving state mandates and the growth of district elections, this year’s crop of candidates—new and returning—seems prepared to accept that more housing must be built, while still asserting that it can be done in a manner that retains the atmosphere many residents find fundamental.

Virtually all the candidates for the Redwood City and San Carlos city councils have adopted that sort of language. Menlo Park, however, remains a battleground. There, Measure V—a citizen-sponsored initiative that some consider draconian—could revive all the old conflicts. Measure V essentially takes away the city council’s land-use authority and requires a vote of the public to rezone single-family properties into multi-family lots. The effect could be to preclude higher density in residential construction.

Behind the measure is a sentiment by residents that they have been ignored by a progressive majority on a council that frequently splits 3-2 in favor of changes that many consider radical. If the initiative passes, it could spur similar attempts in other cities by residents who feel bypassed. If it fails, a new era of expanded housing may be in store for the Peninsula.

The controversy makes it worth remembering that the major changes that created today’s Redwood City encountered their own resistance.

“If you look with some historical perspective, we wouldn’t have had the Farm Hill area built out with housing,” says former Redwood City Mayor Jim Hartnett. “We wouldn’t have had Redwood Shores built. What does that mean about the changing character of our community? What it means is that change is constant.”

The degree of change local residents will accept is driving many city council races throughout the region. As election campaigns head into their final month, how will voters decide among candidates whose positions differ widely in some cases and relatively little in others?

Redwood City Council

District 2

Redwood City’s District 2 is currently represented by Councilmember Giselle Hale, who is not seeking re-election. The district includes downtown Redwood City and the large developable parcels east of Highway 101.

Candidates:

Margaret Becker, retired health professional; member, Redwood City Housing and Human Concerns Committee.

Alison Madden, housing attorney/businesswoman.

Chris Sturken, nonprofit events coordinator; member, Redwood City Planning Commission.

All three candidates are pro-housing. That befits a district where much building has taken place in the last 10 years, and where more could be on the way. The city’s housing plan, which carries the slogan, “Welcome Home, Redwood City,” has identified potential new homesites there.

Of the three, Madden may be the most outspoken on the issue, asserting that state housing mandates, as ambitious (or onerous) as they may seem, could be doubled. Reflecting her history living among and representing the quasi-transitory houseboat tenants of Redwood City’s Docktown, Madden’s emphasis is on homes for purchase.

“Home ownership must become a reasonable prospect; as a renter for over two decades and single working mother, I am committed to making progress on this goal,” Madden says. She adds that she will encourage “small, moderate-sized developers to build things that are available for affordable home ownership.”

If Becker and Sturken seem less aggressive, it’s by a matter of degrees.

“There is a misperception that we’re building too fast,” Becker says. “But we’re required [by the state government] to build to some extent, and we have got to get there somehow.”

Becker believes the challenge is to find a strategy that meets the state’s directives but also satisfies those who worry that the city’s housing plans represent too much change. The current city council has committed to 6,882 new units by 2031, which is 150 percent of the state’s requirement. The present situation will require “some sort of compromise, and consensus is going to have to be a part of it,” Becker says. “A lot of this has to do with very clear, open communication and making sure people feel heard. [But] not everyone gets what they want.”

Sturken’s focus is on making sure the whole city is part of the housing solution, “and not just in District 2.” Other neighborhoods can absorb more housing without damaging their local ambience, he says. The answer, as Sturken puts it, is “the path of least resistance:” Small, one-room units, known as Accessory Dwelling Units, or ADUs, in backyards.

“There are ways to make additional homes blend with existing structures … prioritizing or messaging it as homes for families, for teachers, for aging relatives and reminding residents that it won’t change the look and feel of their neighborhood,” Sturken says.

“Change is good,” he adds. “With anything, when it comes to messaging and marketing, people need to hear it seven or more times before it finally sticks. It’s taking time for people to adjust after so many years of not increasing density.”

Or of height. Sturken says he is “comfortable” with buildings higher than five stories—which seem to be the upper limit in some cities—in the transit corridors of El Camino Real and Woodside Road.

District 5

The district straddles Woodside Road from Woodside Plaza to El Camino and extends to Redwood City’s southern border.

Candidate:

Kaia Eakin, nonprofit executive.

In the pre-district elections era, when candidates ran citywide, Eakin would have been the quintessential “establishment” candidate with connections and credentials from decades of civic and nonprofit activism. Probably for the same set of reasons, she is unopposed in this new district.

“The strength of Redwood City,” Eakin says, “has always been its diversity, from our founding days in the 1860s. … It always has been working class and it has always been welcoming and inclusive.” She adds that, historically, 30 percent of the city’s residents have been immigrants.

—

This story first appeared in the October edition of Climate Magazine

—

Eakin says she understands and shares the concerns of those who fear losing the essential Redwood City, but adds that there are ways to “be smart about where you can build.” El Camino and the Woodside Road corridor seem well-suited for high-rise, high-density residential buildings, she says.

Much of the city’s current profile stems from the postwar building boom of the 1950s, when a car-oriented lifestyle was supreme and one-story commercial and residential construction dominated a landscape notable for its abundant, inexpensive land. But today, Eakin notes, open fields available for construction are increasingly the stuff of nostalgia.

“I love milkshakes and ‘Happy Days’ reruns,” Eakin says. “But I think a lot of people realize it’s not the 1950s.”

District 6

The district is bounded generally by Whipple Avenue, Alameda de las Pulgas, Woodside Road and Hudson Street.

Candidates:

Diane Howard, city councilmember and nurse.

Jerome Madigan, minister and businessperson.

Howard is seeking her seventh term, and is running in a district for the first time. She was elected initially in 1994, served four terms and left the council in 2009. She was again elected citywide in 2013 and re-elected in 2018. She was part of the council that pushed through the reinvention of Redwood City’s downtown area and the construction of high-rise housing in the area.

As the city grapples with commercial and housing growth, Howard says experience is crucial. Of her six council colleagues, two are leaving at the end of this year, another will depart in two years, one is a first-year member and a fifth was appointed to fill a vacancy last month.

She is, she says, someone “who understands how things have been done and [is] open to change.” There are “all these little things” about which she believes she can mentor new councilmembers, such as the importance of serving on regional boards and commissions, how a council meeting is conducted and how to work with city staff.

“There is going to be a learning curve, and I want to help us come together and move forward,” she says. “I’m willing to listen and bend a little. … I feel like I’m a really important piece of this city at this point.”

Madigan has served as a pastor at several local congregations, currently at First Baptist Church in San Carlos. He has worked with youth groups throughout the community, and is also a licensed Realtor.

Madigan says he respects Howard and what she has done for the city, “but we’re looking at many years of a budget deficit, [and] we need new and innovative ways to find revenue. I think it’s time for a new voice. The world has changed so much that it’s time for a fresh approach.”

Howard says she already has a record of supporting the housing projects that have been built or are under construction, adding that she remains sensitive to established neighborhoods and residents who want to protect them.

“You almost have to look neighborhood-by-neighborhood,” she says. “Where can we find space, where can we find room for ADUs? … Some neighborhoods are bungalows, Crafstman, and a predominant number are both styles. Is there something that would complement the neighborhood? How can we make a neighborhood more cohesive?”

She says she supports building in transit corridors and constructing high-density housing on remaining major sites, including Sequoia Station and the location of the former Mervyn’s department store, east of El Camino. Still, she says, “I’m not looking to fill every nook and cranny in Redwood City with housing.”

Madigan says he wants to build “thoughtfully, sustainably and with the community in mind. I’m neither pro- or anti-development. I’m anti-bad development.”

He also believes the city can demand more improvements from builders. “We need to negotiate great deals with developers. … I don’t feel like we’ve done a great job of that,” he says.

In addition, he says, he “would not put height off the table. … I’m not in a rush to take away height restrictions. But as I look at the long view of the Peninsula, we have to see that up is one of the only directions we can go.”

Menlo Park City Council

San Carlos and Menlo Park are at either end of the district election spectrum, and the salient debate of the day over housing.

Menlo Park was one of San Mateo County’s first cities to enact district elections. In a sweeping turnabout four years ago, a status-quo majority was cast aside by what many observers consider one of the most progressive majorities on any council in the county.

Councilmembers Cecilia Taylor (District 1) and Drew Combs (District 2) are unopposed, leaving Mayor Betsy Nash the only incumbent with a challenge—from former Councilmember Peter Ohtaki. He lost to Nash four years ago in a 25-point landslide. Since then, Ohtaki has twice run unsuccessfully for the state Assembly as a Republican.

He is hoping to catch a presumed wave of dissatisfaction with a Nash-led 3-2 majority that has been criticized for its policies on housing growth, as well its reluctance to fully fund the police department and its attempt to repurpose the city’s utility user tax, among other complaints. Ohtaki has embraced Measure V on Menlo Park’s ballot as an expression of discontent that includes a sense among some that their concerns are not being heard.

San Carlos City Council

In San Carlos, five candidates are running for three seats. San Carlos still operates under a citywide election system, which might seem to favor incumbents Sara McDowell and Adam Rak, each seeking a second term. That leaves three challengers—Pranita Venkatesh, John Durkin and Alexander Kent—fighting for the remaining seat.

Venkatesh operates a local daycare center and serves on the city’s Economic Development Advisory Committee. To some, she fits the mold of an establishment insider more closely than the other two candidates.

Durkin works in finance and accounting in retail corporate offices. He also has been an active volunteer in a host of city traditions, including the recently revived Hometown Days.

Kent declined to be interviewed for this story, although he did offer to speak anonymously after the election. Kent ran for the Burlingame City Council in 2013 and was rejected in a bid for the Belmont Planning Commission in 2016.

All four candidates who consented to interviews described similar opinions about housing—more needs to be built, but the community’s character must be preserved—and no one is wandering off the beaten path in the City of Good Living.

“We must balance quality of life with the need to increase the housing supply and affordability,” Venkatesh says. “Our housing is not sustainable if teachers, police officers, retail employees, even biotech workers can’t afford to live in San Carlos.”

Durkin says, “I do wonder how much impact I [would] have on housing as a councilmember. I do question the big houses that are being built” and how they affect traffic congestion and the character of neighborhoods. He says he would support partnerships with local nonprofits that identify empty bedrooms as opportunities for rentals.

The Parlance of Politics

Admittedly, these are political campaigns. Candidates try to win over voters, not alienate them. The common course of action is to seek a rhetorical middle ground. Campaigns do have the capacity to gloss over more deep-seated disagreements.

There is a fair distance, for example, between Howard’s desire to avoid filling “every nook and cranny” and Sturken’s assertion that all of Redwood City, and not just District 2, needs to share the burden. His support of ADUs seems to be precisely a strategy of filling available nooks and crannies. But beyond that, there appears much agreement, at least at a high level, because San Mateo County has been changed profoundly and irreversibly by an intractable economic reality.

A county that once boasted little more than bedrooms and hometown retail stores has become a juggernaut—a center for employment at the highest levels as measured by sheer numbers of workers and their average incomes. Residents have enjoyed the prosperity that has come with the county’s economic transformation. And many have acquired considerable wealth through the county’s tenfold increase in home values over approximately the last 40 years.

Today, many homeowners and landlords are fearful their property values—sometimes leveraged into other investments and often inflated by anti-growth policies that have restricted the supply of housing—will be undermined by an increase in residential construction. Others rue the potential loss of a suburban lifestyle that grew out of low-density neighborhoods filled with one-family homes. Still others oppose (and frequently moved away from) “bigness” in general, preferring the village-like feel of small houses and the one- and two-story businesses that still predominate in shopping districts such as Laurel Street in San Carlos and Santa Cruz Avenue in Menlo Park.

Nonetheless, for a growing number of leaders along the Peninsula, the question no longer appears to be whether to build or not to build. It’s how, and how much. This November, amid all the rhetorical back-and-forth, the real issue on the ballot may already have been acknowledged—the reality that change is always a constant.