Scottish American naval captain John Paul Jones earned fame during the American Revolution when, during a battle off the northern coast of England in 1779, he responded to a British suggestion about surrender by retorting, “I have not yet begun to fight.” (Jones’s fleet ultimately prevailed, against heavy odds.) Jones also was involved in asking France to aid the Americans; during the discussions, he vowed “to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast; for I intend to go in harm’s way.”

Today, navigation charts of San Francisco Bay warn of a shipwreck near Redwood City that’s about all that’s left of a fast ship sent into harm’s way during World War II. The remains are those of the USS Thompson, which I have written about in The Journal of Local History. I decided to delve further into the history of this class of ship after reading the obituary of Carl Clark of Menlo Park.

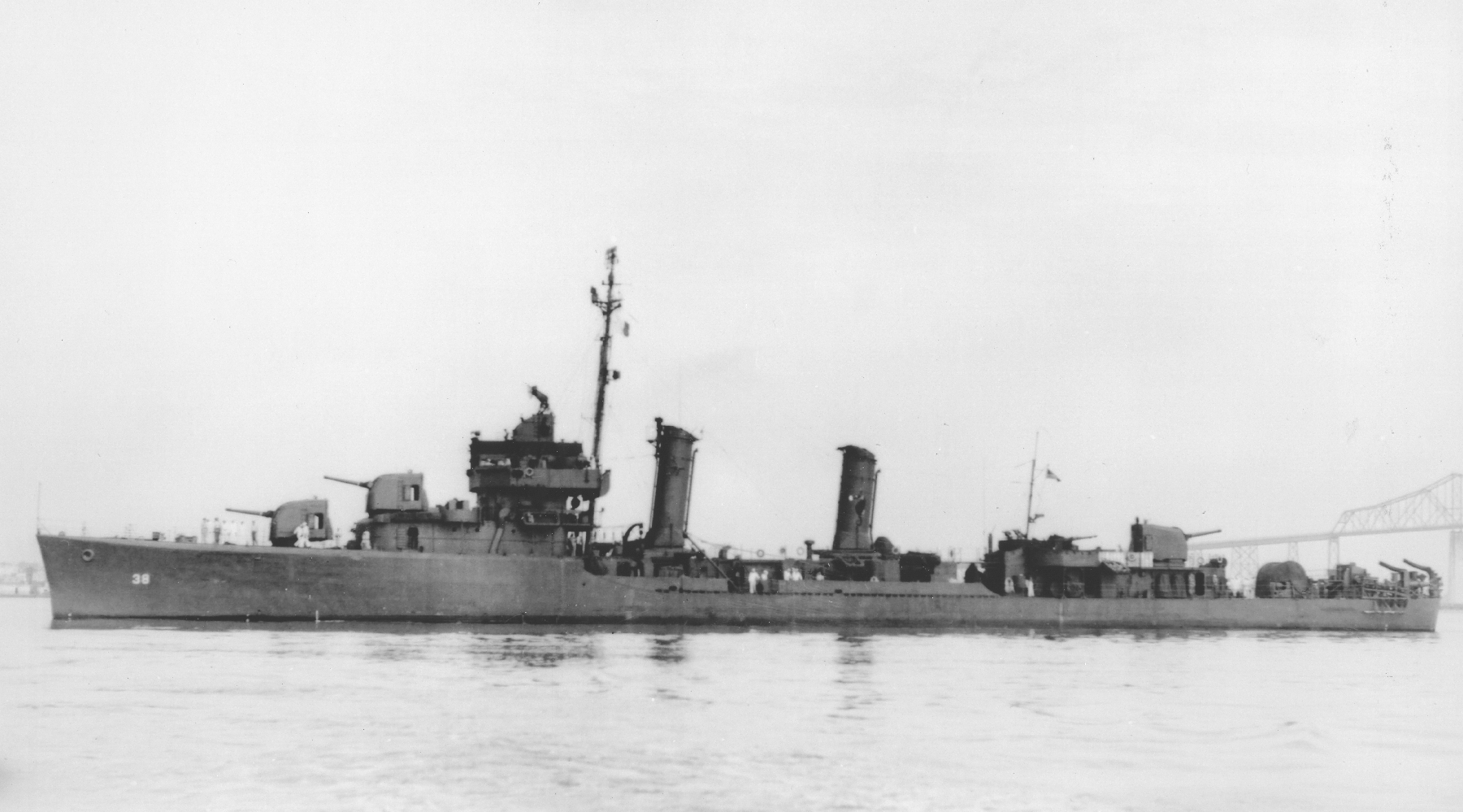

Clark, who died in 2017 at age 100, served aboard the USS Aaron Ward, a destroyer similar to the Thompson. None of the obituaries about Clark that I read gave any history of the Ward, so I opened the always captivating book, “Warships of the World,” published by Cornell Maritime Press and written by Roger Kafka and Roy L. Pepperburg.

I got an eye-opening naval education. It was so fascinating that my attention strayed from the Thompson, about which I will write more next month. It, too, has an intriguing story. But for now, the USS Aaron Ward.

The 1946 edition of “Warships of the World” reveals that the Ward sank a Japanese submarine at Pearl Harbor more than an hour before Imperial Japan attacked on the morning of December 7, 1941. The Ward wiped out the sub at 6:30 a.m. According to the book, the destroyer’s crew notified the base, which was hit beginning at 7:48 a.m.

The Ward was built at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo in 1918, too late for World War I. The ship made up for its lack of combat experience in that conflict by seeing plenty of it in the next war.

—

This story first appeared in the January edition of Climate Magazine

—

After Pearl Harbor, two of the Ward’s four smokestacks were removed as part of its conversion to a “fast transport” that faced danger many times in earning 10 battle stars, including in the Solomon Islands and at Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. At the 1944 Battle of Ormoc Bay, an extension of the huge Leyte Gulf confrontation, torpedoes damaged the Ward so severely that U.S. forces themselves sent it to the bottom. The Ward’s end came on December 7, 1944, three years to the day after the vessel fired the first shot of the war.

The larger (and greatly decisive) Battle of Leyte Gulf was the biggest naval clash in World War II, and depending on how it’s viewed, perhaps in history. Fought during four days in late October 1944, it engaged more than 200,000 naval personnel. According to the website of the U.S. Navy’s Naval History and Heritage Command (available at www.history.navy.mil), the battle “completely destroyed the strategic threat posed by the Imperial Japanese Navy.”

Pentagon records show the U.S. lost seven warships to Japan’s 26. For Japan, the losses of vessels and crew were its greatest in history. The human cost was staggering—more than 23,300 U.S. soldiers and sailors killed and an unfathomable 419,912 Japanese dead and wounded.

The battle began after Japanese commanders, anticipating the Allied attack to re-take the Philippines after Japan captured the U.S. commonwealth in 1942, prepared what the U.S. Navy’s website describes as “a desperate, multi-pronged attempt” to devastate U.S. naval forces and intercept the Allies’ amphibious landing, which started October 20. Raging from October 23 to 26, the naval clash—in reality, a widely dispersed series of smaller conflicts—involved battleships, destroyers, cruisers, PT boats, aircraft carriers and numerous fighter and bomber squadrons.

Included were U.S. Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet and Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet; despite being outnumbered, just three vessel groups from the Seventh Fleet turned back Japanese naval forces on the morning of October 25. By the next day, the Allies had established sea and air control throughout the region for the duration of the war.

Next month: The story of the USS Thompson and how it came to rest off Redwood City on the mudflats of San Francisco Bay.