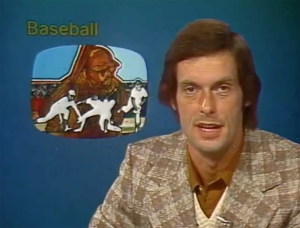

Since the age of eight, Pete Liebengood knew what he wanted to be: a sportscaster. Growing up in Santa Barbara, his heroes weren’t Maury Wills or Sandy Koufax but Vin Scully, the legendary play-by-play announcer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Liebengood even created his own baseball board game, using player trading cards, a sheet of butcher paper and a pair of dice so he could announce fictional games in his bedroom. The wannabe man-behind-the-microphone drove his parents nuts when he would yell excitedly calling a double play or a home run. Yes, the kid who would become a well-known Bay Area sportscaster knew just what he was going to do in life. And he did it, too, for 28 years — in spite of the spitball that was thrown at him.

Liebengood can’t pinpoint where his love of sports came from. Perhaps it was watching professional boxing in front of the local store at night with his dad. Television was still a novelty, and the manager would leave rows of TV sets on at all hours to attract customers, the tiny black-and-white screens glowing like a beacon to the future. Or perhaps Liebengood got the broadcasting bug listening to the radio, sprawled out on the living room couch, while Rocky Marciano pummeled his latest opponent. Somewhere along the line a seed was planted, because from an early age Liebengood realized he enjoyed listening to a sporting event more than watching it.

His family made the move from Pontiac, Illinois, to Santa Barbara when he was six years old. It was a dramatic change of scene, but trading the icy snow-covered fields of Illinois for the golden coastal hills of Southern California wasn’t such a bad deal.

Liebengood grew strong and powerful, becoming an All-American high school football player. When it came time for college, he sought only schools that offered a major in radio, television and film. San Francisco State not only was one of the few colleges that offered such a degree but also had a very good football team. It was a perfect fit, as Liebengood excelled in his studies, while becoming an all-conference offen sive tackle.

sive tackle.

After graduation and a six-month stint in the National Guard, he landed in Eureka for his first job, at KIEM television and KRED radio. “It was a double injection of learning how to do things in a hurry,” Liebengood remembers. “I did the sports on TV and read the news on radio.”

His stay was just 14 months; he was out of Eureka as soon as a job opened up at Sacramento’s 50,000-watt station, KFBK. Six months later, he moved on to KCRA, a larger Sacramento station where he got the opportunity to work multiple jobs: reporting, anchoring and sports. For seven years Liebengood did it all. And he loved it.

Then came the call from KRON-TV in San Francisco, another irresistible leap in Liebengood’s career. He was the dedicated sports guy with the occasional fill-in as anchor, but at the same time was given the flexibility to pursue outside freelance work, which included a full slate of play-by-play opportunities. Moreover, after his five-day gig concluded, KRON had no problem with his traveling to Canada to announce World Cup skiing, rodeos in Dallas for ESPN, or boxing in Atlantic City.

Liebengood was on a roll—until the realization he was missing out on watching his two sons grow up hit him. “That’s when I decided to pull way back.” After 12 years he left KRON to replace Jan Hutchins as news anchor at KICU, but not long after, he moved on to start his own production company.

However, in the beginning of his career, life threw a spitball, one that would probably surprise his fans as much as it did Liebengood.

“This is a part of my life I have never told anyone except my wife,” he says. “It first hit me at KFBK anchoring the news. I was 24 years old. Right in the middle of my three-minute newscast, my heart began to race, my knees to shake violently and I became so dizzy I nearly fainted. Thought I was having a heart attack—I had no idea what was happening to me. Thank God I somehow managed to muscle through it.”

Liebengood was experiencing an anxiety attack. And for years he dealt with these symptoms every time he placed himself in front of a camera or microphone—sometimes twice a day. ”Sure I considered giving it all up but I just loved what I did,” he says. “There wasn’t a day when I wasn’t excited about going to work. So I decided to fight it.”

Commuting from Walnut Creek to San Francisco meant daily crossing the Bay Bridge. Unfortunately, bridges are another trigger for his anxiety. “Basically, any situation where I feel trapped causes me anxiety. The one-way confines of a bridge offers no escape and so it is every bit as bad as being in front of the camera. I would tense up and sweat so badly it was a miracle that I never caused an accident . . . But once the red light on the camera went off, or I came off the bridge, the symptoms immediately departed.”

Interestingly, Liebengood managed to hide his disorder from family, friends and co-workers—something that amazes him to this day. “I became very good at disguising my condition.

“It wasn’t until 10 years later, when I was at KRON, that I went to a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. It could be that I suffer from a chemical imbalance or it could be something else. To this day I have no definitive answer,” he says. “Thankfully, the right meds help manage the intensity of the attacks, but they don’t make the symptoms go away totally. Still take them.”

In an attempt to slow down, at one point, Liebengood left television and began his own production company. “I also wanted to develop TV shows and had some success with one particular pilot we titled ‘Partners.’ The show centered on following pairs of police, fire and medical teams, among others, looking into their lives as a whole. It won a national Telly award and showed at the San Jose Film Festival but never made it to syndication.”

However, the effort wasn’t all for naught: It was while following one young police officer as he attended classes at Cañada College that Liebengood met Alicia Aguirre. “After filming the officer in class, I found what I really was interested in was his professor. So I asked him if he would inquire about her current relational status,” Liebengood recalls with a smile. “She thought the guy was asking for himself and got pretty upset until he quickly set her straight on who was really asking.”

A lunch was arranged and, as they say, the rest is history. Liebengood and Aguirre, a Redwood City Councilwoman and former mayor, have been married 19 years.

One day, Liebengood’s pace and method of dealing with anxiety caught up with him: He found himself on an operating table on the receiving end of a quintuple bypass. It was time to put the brakes on in a big way. He sold his production company and started “Fresh Takes,” teaching video production to high school-age students. He kept that up for four years until an old girlfriend he saw at his 40th high school reunion put him onto an idea that got his creative mojo going in a new direction.

The suggestion was that Liebengood should write a book about the San Marcos High School class of 1962. “Took me a few years to mull it over,” he says, “but then I got to work. It was total fiction, a murder mystery involving the graduating class of 1962.” He self-published the novel and gave it away at his 50th reunion. His old classmates loved it, which was all the encouragement Liebengood needed to start writing in earnest. To date he has written and self-published six novels: “The Class of ’62,” “Accidental Droning,” “Amen Corner,” “Honeyball,” “Mylovie.com” and “Rendez-vu.” “They are all mysteries with humor—I like to call it ‘mystery-lite’,” he says.

Liebengood has considered penning a work of fiction entitled “What a Panic!” that features a lead character who suffers from the same anxieties he does. Not to sensationalize the disorder but to let those who are suffering from anxiety and panic attacks know that they can overcome them. He is one of those fortunate enough to have fulfilled a lifelong career dream, though some would ask why he didn’t just give into the relentless disorder that plagued him and seek an easier path. It was certainly available to him.

Perhaps Liebengood kept hearing Vin Scully whisper in his ear, “Ignore the spitball.”

So far, tie game.