A rusting hulk on the mudflats off Redwood City is the tombstone for an unheralded class of ships that sailed in harm’s way during World War II. It’s true that the ship itself, the destroyer USS Thompson, didn’t see combat. Nevertheless, it had brushes with history, among them when it escaped from one of the worst peacetime disasters in navy annals.

The destroyer that lies near the mid-bay boundary with Alameda County served in the war as the target for dud bombs dropped from airplanes during practice runs. While the Thompson served as a floating punching bag, other ships of its class, obsolete for years, were fighting the Axis powers in both the Pacific and the Atlantic.

One, the USS Ward, sank a Japanese submarine at Pearl Harbor moments before the naval base was bombed early in the morning of December 7, 1941. The Ward was sunk in 1944—on December 7, 1944, to be exact. Coincidence? Here’s a better one: The Ward was so badly damaged by the Japanese that it was abandoned and later sunk by an American ship commanded by the same captain who had been in charge of the Ward at Pearl Harbor.

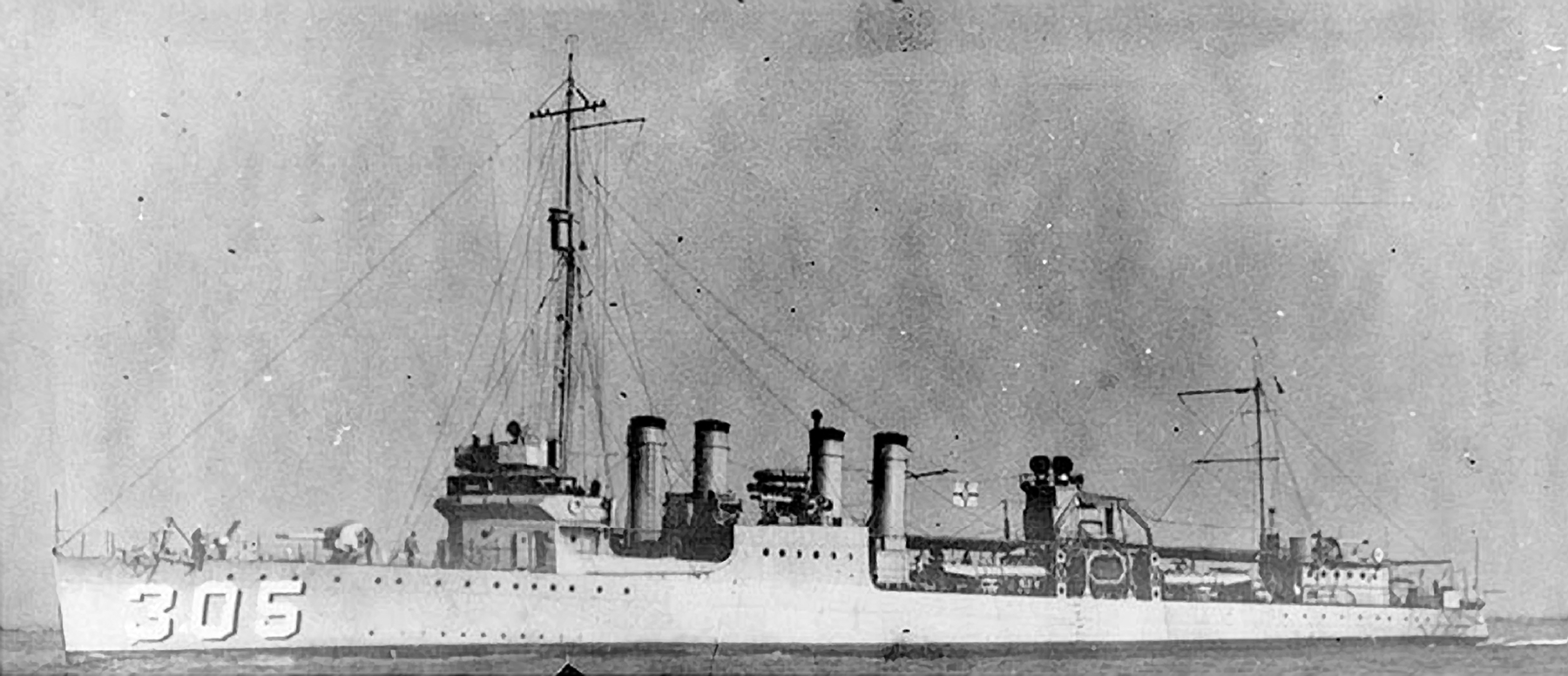

Today, the wreckage of the Thompson, a 314-foot Clemson-class destroyer built in 1918, can be visited by intrepid kayakers who paddle the six miles from Redwood City.

Local resident Jerry Pierce is one of them.

—

This story first appeared in the February edition of Climate Magazine

—

“It is first visible as we leave the Port of Redwood City, and a small bump on the horizon toward Fremont is our guide to the wreck,” Pierce told the Journal of Local History in 2018. He added, “If weather is nice and the tides are good, it takes a little over an hour” to reach the vessel.

The Thompson was one of scores of “four-piper” destroyers, a name that stemmed from the number of smokestacks that dominated their silhouettes. Even before Pearl Harbor, the ships played a key role in World War II. In 1940, the U.S. provided 50 of the “mothballed” aging vessels to Britain, which was already battling Nazi Germany.

The Thompson’s main claim to fame came when it was part of a flotilla of 14 destroyers sailing from San Francisco to San Diego on September 8, 1923. The lead vessel made a wrong turn and smashed into jagged rocks near Point Conception in Santa Barbara County. Seven ships were lost and 23 sailors killed. The Thompson was last in line, and its skipper avoided the fatal maneuver.

Today, however, little is left. According to a 1976 story in the Redwood City Tribune, the ship was “attacked relentlessly by Army Air Corps P-38s, P-51s [and] Navy Corsairs” during bombing practice.

Peter Evans, an emeritus UC Berkeley professor, penned an extensive article on the Thompson for the May 1997 issue of the sailing magazine Latitude 38. He said the Navy decommissioned the ship and then repurchased it in February 1944 for one dollar. The Thompson, Evans wrote, was used for target practice “for the rest of the war and probably sometime thereafter.”

Evans said a local man, who did not want to be named, recalled how he conducted informal salvage operations on the Thompson when he was a student at Sequoia High School in the early 1950s. He said he sold as much as $300 (a lot of money then) in materials in a day to a scrap dealer. The man said he and his friends also held parties on the Thompson.

“They still had the canvas bunks below, and even magazines left behind by the last crew,” he said. “We made fires on the deck to roast hot dogs and generally partied it up, sometimes for whole weekends. The old ship was good to me.”

Even before, the Thompson had a reputation as a party boat. Stricken from the Navy list in 1930, it was initially sold for scrap. But awhile later it was still active—as a restaurant and bar during Prohibition.

The Thompson isn’t the only World War II-era destroyer that sits on or near San Francisco Bay. The USS Corry, sold by the Navy in 1930, became stranded on the Napa River during its voyage to the scrapyard. The wreckage is widely known to boaters. Other such vessels also could still be afloat, according to Commander John Alden, warship expert and author of “Flush Decks and Four Pipes.” Noting the ships’ versatility, he wrote in his 1965 book that “perhaps even now one survives as a barge.”

Or at least a venue for a floating bachelorette party.