My mother, Barbara, was heavily involved in San Mateo County politics as an operative, campaign worker and campaign manager, which means I grew up surrounded by political discussion, debate, campaigns and candidates.

The first candidate I met was Leo Ryan, who was in my living room, conducting a campaign coffee, when I came home one afternoon from the fourth grade.

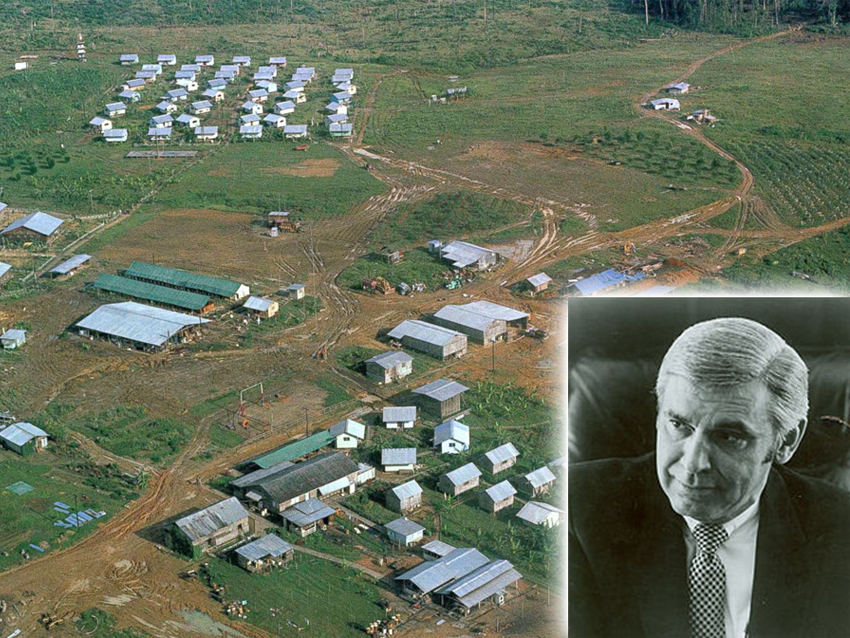

The 40th anniversary of Jonestown has generated an expected and understandable series of news stories about the horrendous tragedy in that distant jungle.

But it always has felt to me that Leo was an overlooked part of this story, not only because he was the catalyst for what was an inevitable march toward madness and mass murder, but because of who he was – a true maverick, a rule-breaker and a bold personality.

So, in observance of the 40th anniversary of his death, consider this a tribute to a man – frequently and flamboyantly flawed, but one of us, our congressman, our homegrown politician who was, in many ways, truly larger than life.

In addition to cluttering up my living room one fall afternoon, Leo was an English teacher at Capuchino High School in Millbrae, and he led the school’s famous marching band to Washington, where it marched in President Kennedy’s inauguration parade. My brother, Rick, was part of that expedition.

Even then, he was angling for higher office and the legend goes that while the high school band toured Washington, Leo was roaming the halls of Congress, paving the way for his future career.

He served on the South San Francisco City Council at a time when the politics of that city were thoroughly dominated by the Italian-American community, and his election remained a source of resentment among those who thought his seat should have been theirs.

This resentment extended to his election to the state Assembly, representing the northern half of San Mateo County.

By the time he was elected to Congress, he was easily the most dominant political figure on the Peninsula. In one of his elections, he secured the Democratic and Republican nominations and he appeared on the November ballot as the sole candidate.

LEO. JUST LEO: You may have noticed that I’ve been referring to him as Leo, rather than his last name or his title. Everyone knew him as Leo. He was everywhere – speaking to local groups, talking with local newspapers, and gaining headlines for his “investigative representation,” in which he would go places and confront issues.

That was his trademark. He served as a substitute teacher in Watts after the riots there, posed as an inmate at Folsom Prison, and confronted pelt hunters slaughtering baby seals in Newfoundland.

He believed that bringing attention to issues and conditions would spark public policy to address those issues. If, along the way, he gained attention for himself, well, it was only a reasonable result of the risks he was willing to take.

Only one member of Congress has come close to matching Leo’s unique ability to generate publicity that addressed critical issues and raised the member’s profile. That’s Jackie Speier, Leo’s protégé, whose own ability to pull an issue into the spotlight has made her a figure of national reputation.

Leo looked like a congressman. He had silver hair, carefully coifed, and a booming voice. He was well over six feet tall, his face had strong and distinctive features and he could dominate any room he entered.

He was not a team player in Congress and a number of insiders dismissed him as a lightweight, but he didn’t care. He had his own agenda and it wasn’t the classic mindset that you had to go along to get along.

He was proud of his local roots, however, and what was said about him locally mattered to him a great deal. He once sent a handwritten note to my mother, apologizing for a disagreement. As a political reporter, I covered his last campaign for Congress in 1978, and I recall him calling me into his office and conducting a detailed and loud critique of one of my stories.

COME TO JONESTOWN: All that means I was well acquainted with Leo, not just as a political reporter, which I was in 1978 for the Redwood City Tribune, but as a family friend.

On election nights in San Mateo County, it was customary in those days for candidates to make personal appearances at the offices of the county Elections department in Redwood City, where they could get the latest results and speak with the press.

Covering the election for the Redwood City Tribune, I bumped into Leo in the Elections office and, leaning against a row of three-drawer filing cabinets, we talked about the election.

Then he turned the topic to his upcoming investigative trip to Guyana to check on the Peoples Temple. He said something about doing so on behalf of some constituents.

Familiar with Leo’s crusading, some would call it grandstanding, I was skeptical that this was anything more than a junket, and I said as much to him.

I told him I thought he would spend an hour in Guyana and then zip off to some exotic island.

No, he said, this is serious, and he said I ought to join the group of reporters also making the trip. I told him he needed to talk to my editors.

Apparently, he called them the next day and urged them to send me on the trip. They declined. The Redwood City Tribune was a small newspaper that lacked a lot of resources, and they had spent a good chunk of change earlier in the year sending me on a two-week trip around the state with Jerry Brown and Evelle Younger, covering the governor’s race.

Some days later, of course, we got the news about Leo and the Jonestown massacre, which included the shooting of several of the reporters on the trip.

We met in the Tribune newsroom the next day and Managing Editor Glenn Brown, City Editor Bruce Lee and Editor Dave Schutz decided to send me and Bill Shilstone to Washington in time to cover the return home of Leo’s body and to do what reporting we could on those who were returning from Jonestown.

It was a Sunday morning in the days before ATMs and we didn’t have a petty cash fund on hand, so Glenn Brown contacted his pastor at his church and he gave us the money from that morning’s collection plate. I don’t know how much it was, I just remember a lot of small bills. Shilstone, who doubled as an assistant city editor and education reporter, handled the money.

Off we went to Washington. It was a different time. I was able to get into the hospital room of an NBC sound man who had been wounded and into Jackie’s hospital room, although she was in no position to answer questions.

On the flight home, I sat with Joe Holsinger, Leo’s closest friend, as he reflected on his friend’s career. Leo had been getting ready to run for Superintendent of Public Instruction. He was going to push for a statewide ballot measure embracing charter schools. He was going to shake things up.

A UNIQUE BRAND OF FEARLESSNESS: He was always willing to shake things up. It’s what he did. He was fearless. He was convinced his office carried enough stature that it would protect him.

Who would be crazy enough to attack a member of the United States Congress? In fairness, no one knew how crazy Jim Jones was.

All Leo knew was that some of his constituents were scared, terrified for their own family members. And he was determined to do something about it. He knew Congress would do little or nothing. So he decided to take direct action.

He did what he always did. He went to see for himself. It was an act of courage. It got him killed.

As stories pour forth on the events in Jonestown, I like to remember Leo – fondly, of course, with an appreciation for how fully human he was, and with respect for a public servant who saw his job as a platform for courage.

I’m forced to ponder if we’ll ever again see anyone quite like him.

Contact Mark Simon at mark.simon24@yahoo.com.

*The opinions expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Climate Online.