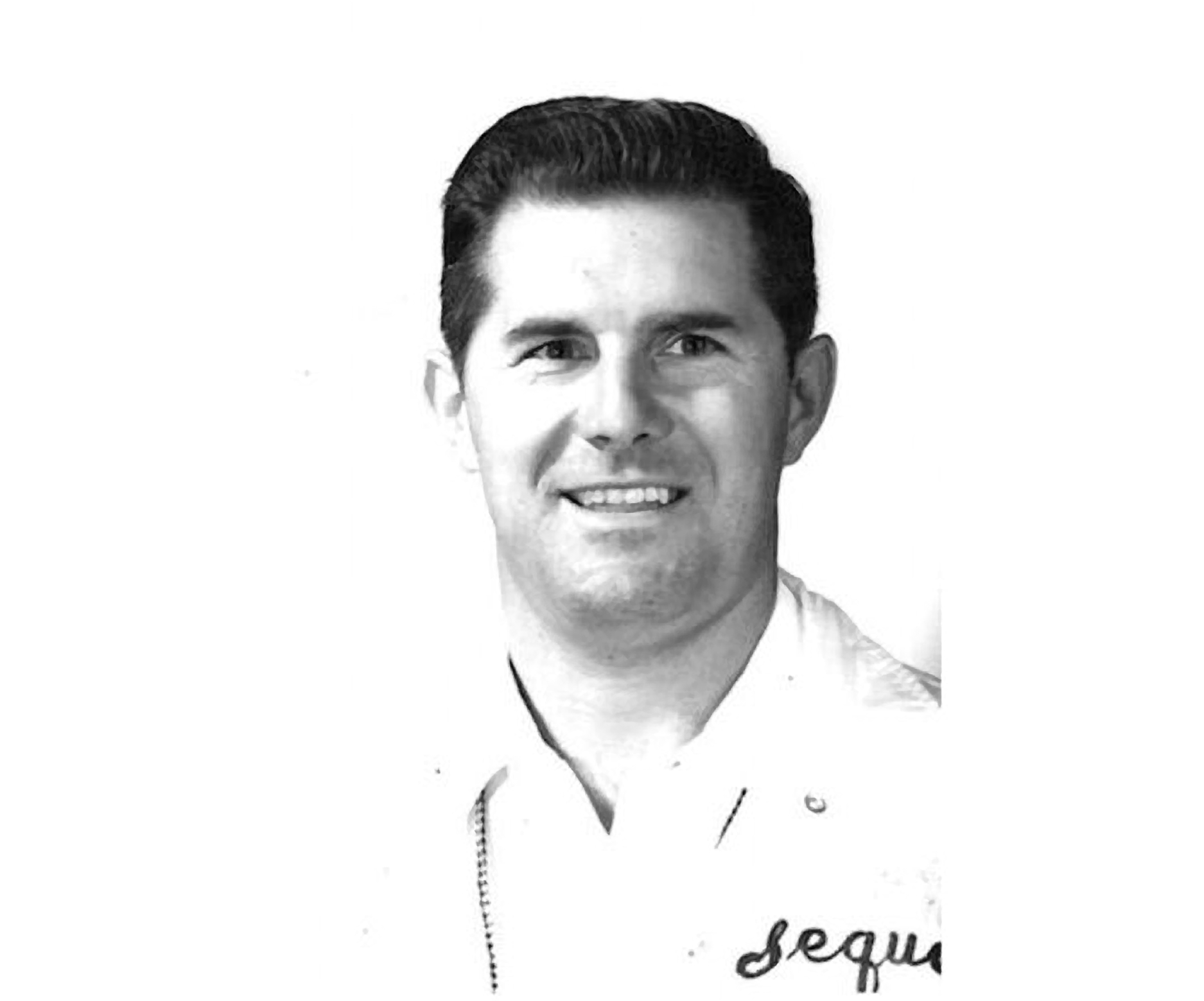

The recent passing of Sequoia High football legend Joe Marvin recalled a time when prep football games drew thousands of fans, including those who unashamedly rooted for the Cherokees, a mascot replaced decades later by the more politically sensitive Raven.

Marvin was 93 when he died Feb. 23 at his home in Aptos. Between 1958 and 1963 his Sequoia teams won 33 straight games in what came to be called “the streak,” which was ended by a Carlmont High School victory. In all, Sequoia won 51 of 58 games during Marvin’s tenure at the Redwood City high school.

The 33 consecutive wins amassed four South Peninsula Athletic League championships from 1958 to 1961, a Peninsula record. In 1960, Sequoia beat Palo Alto 19-7 before 18,254 spectators at Stanford Stadium to become the top-ranked team in Northern California. Marvin was named Northern California Coach of the Year in 1961. Large crowds for the “Little Big Game” between Paly and Sequoia weren’t all that unusual. The 1968 encounter reportedly drew 30,000. The rivalry between the two schools went back to 1927 and ended in 1975 when Palo Alto switched leagues.

Football’s Stars Aligned

Marvin, who was a tailback at UCLA, may have benefited from what can be described as “a perfect football storm.” He was “the grateful custodian of a unique, five-year Mother Lode of athletic talent whose simultaneous emergence at Sequoia remains unexplained to this day, and likely will never be seen again,” veteran journalist James Gallagher wrote in 1992 when Marvin was inducted into the San Mateo County Sports Hall of Fame.

Marvin’s players included guard Bob Svihus, who would go on to USC, the Oakland Raiders and New York Jets; and center Rich Koeper, destined to be an All-American at Oregon State before playing pro ball for Green Bay and Atlanta. And, of course, there was the sensational Gary Beban, a Heisman Trophy winner at UCLA who later played pro ball for Washington.

—

This story appeared in the March edition of Climate Magazine.

—

The two linemen were present at the beginning of “the streak,” while Beban saw its end. Svihus, now 74 and living in Salinas, said Marvin was “a true gentleman” who was “an outstanding individual, not just an extraordinary coach.” He helped “a lot of boys become men,” Svihus said. “He was a role model to me. My parents were divorced, and I didn’t see much of my father.”

Single-Wing Days

In a 2011 interview with The Journal of Local History, Gallagher, who passed away in 2014, noted that Marvin used the old single-wing offense that dates back to the “leatherhead” days of football. “Some opposing coaches didn’t know quite what to make of it,” he said.

Briefly, the single-wing featured an unbalanced line with two linemen on one side of the center and four on the other. Also, the formation has a long snap from center with no handoffs needed. Gallagher was near poetic in his description of the flight of Marvin’s single-wing when he penned this in the 1992 article: “For an instant, as they veered in unison to the point of attack, three to five blockers would achieve a ballet-like symmetry in advance of the prancing tailback before exploding into the midst of protesting defenders.” Marvin learned the single-wing attack as a tailback under UCLA coach Red Sanders from 1949 to 51.

Marvin and his wife, Jean, raised three children in Redwood City before he moved to the college level, where he coached the backfield at Washington State and later at Cal. After moving to Aptos, Marvin coached at Cabrillo College where his record as head coach was 75-22-5. Cabrillo won four Coast Conference championships under his leadership from 1974 to 1983 – creating another legacy.